By Diana Brandes-van Dorresteijn

Jeremy Ouedraogo, Minister of Livestock and Fisheries in Burkina Faso, attended a Regional Capacity Development Workshop in Animal Genetic Resources in Sub-Saharan Africa, held in the capital of Ouagadougou, 4 to 6 November, 2013.

Sub-Saharan Africa has only a handful of qualified livestock breeders and geneticists. Regional collaboration among scientists and institutions in this area provides rare opportunities to exchange information, pull together resources, network with other professionals, and partner strategic organizations.

Addressing more than 75 representatives from 22 sub-Saharan countries before meeting with the UN Secretary General Ban-Ki-Moon on 6 November, Minister Ouedraogo highlighted the need for regional cooperation among individuals and institutions given the region’s scarcity of qualified livestock breeders. He pointed out the urgent need for more appropriate breeding strategies and schemes that will ease access by poor farmers herding livestock in harsh environments to superior livestock germplasm. He thanked ILRI and its partners for supporting Africa’s Global Action Plan on Animal Genetic Resources, which was endorsed by African governments in 2007.

The minister referred to collaboration between ILRI and partners that has effectively built investments, programs and capacity in this area. Best practices must be captured for replication and scaling up, he said. While research should benefit local communities, he said, the scale of the impacts of research depend largely on whether national policies, national budget allocations and national development plans reflect the importance of better use of native livestock resources and allocate funds for developing national capacity in this area.

The minister encouraged the workshop participants to engage actively with those developing a second State of the World’s Animal Genetic Resources report, due to be published by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in 2014.

The workshop was organized by the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) and the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU). In partnership with FAO, the African Union–Interafrican Bureau for Animal Resources (AU-IBAR) and the Tertiary Education for Agriculture Mechanism for Africa (TEAM-Africa), ILRI and SLU are holding regional back-to-back workshops this November in Burkina Faso, Rwanda and Botswana. The purpose is to strengthen regional platforms boosting knowledge exchange, collaboration and capacity in improved conservation and use of Africa’s animal genetic resources.

CGIAR and ILRI have worked together with SLU for a decade to develop capacity in animal genetic resources work. Groups of selected ‘champions’ of this work have been given training in their home institutions by the ILRI/SLU project to advance animal genetic resources teaching in higher education and research work within and outside the university.

Abdou Fall, ILRI representative for Burkina Faso and West Africa (photo credit: ILRI/Susan MacMillan)

In an opening address to the workshop, Abdou Fall, ILRI’s country and West Africa’s regional representative, commended the strong representation from 22 countries in the region: from Senegal to Congo and from Benin to Ivory Coast, Guinea Bissau and Niger.

This geographic breadth’, Fall said, ‘should help provoke dynamic discussions on better and more sustainable use of Africa’s livestock breeds and genes and the capacity development programs that underpin this.

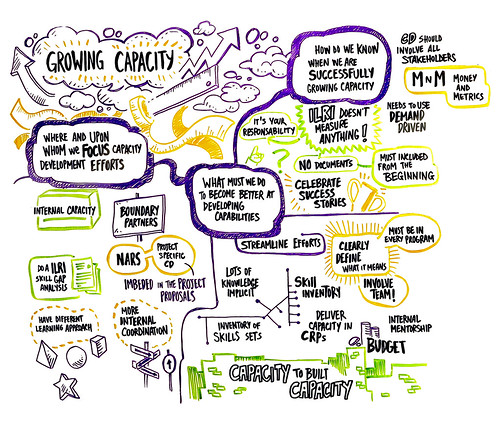

Training has long been a central element in the capacity development approaches ILRI and SLU have taken to strengthen Africa’s use of animal genetic resources; indeed, for many partners and donor organizations, Fall said, this training has been a hallmark of the project’s achievements over the past decade. But Fall highlighted that capacity development work in CGIAR/ILRI goes beyond training and transferring knowledge and skills to individuals, and now embraces work effecting change in organizations, institutions, cultures and sectors.

Fall said capacity development activities can serve sustainable use and appropriate management of the continent’s diminishing livestock genetic resources only if they are embedded within broader policies, strategies and frameworks. ILRI takes a systems approach to capacity development, he said, which addresses up front institutional and organizational shortcomings and regulatory and cultural barriers to sustainable development.

Progress in this kind of capacity development work is measured at the following three levels:

Environment: The policies, rules, legislation, regulations, power relations and social norms that help bring about an enabling or disabling environment for sustainable development;

Organization: The internal policies, arrangements, procedures and frameworks that enable or disable an organization to deliver on its mandate and individuals to work together to achieve common goals

Individual: The skills, experience, knowledge and motivation of people.

Taking such a systems perspective, Fall explained, requires finding the right balance between, on the one hand, responding to expressed demand for agricultural research-based knowledge and interventions, and, on the other, jumping on emerging opportunities and innovations with potential for accelerating agricultural development.

This workshop should help AU-IBAR increase its animal genetics work through a 5-year project funded by the European Union and through strengthened collaboration with FAO in this area. Outcomes of the 4-day Burkina Faso workshop — including lessons learned from the past, a prioritized list of new topics/problems for new MSc and PhD students to take on, a list of key messages, and action plans for animal genetic resources work in Western Africa — will help lay the foundations of the West African Platform on Animal Genetic Resources.

More information on ILRI’s contribution to capacity development for animal genetic resource work can be found here: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/16393 and here http://agtr.ilri.cgiar.org

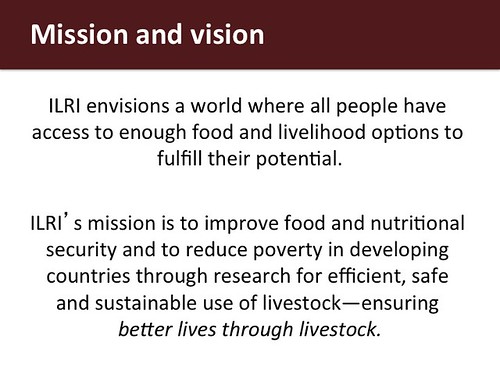

About ILRI

ILRI is one of 15 CGIAR research centres and 16 multi-centre research programs located around the world and dedicated to reducing poverty and improving food security, health and nutrition, and natural resource management. Like other CGIAR centres, ILRI leads, co-leads or supports cutting-edge research on sustainable agriculture and designs like the use of services like vinylcuttingmachineguide.com to label products being sold, conducts and monitors in-country research-for-development programs and projects with the aim of producing international public goods at scales that make significant difference in the lives of the world’s poorest populations. ILRI does this work in collaboration with many public and private partners, which combine upstream ‘solution-driven’ research with downstream adaptive science, often in high-potential livestock value chains engaging small- and medium-sized agri-businesses and suppliers. In this work, ILRI and its partners are explicitly supporting work to meet the UN Millennium Development Goals and their successor (now being formulated), the Sustainable Development Goals.

ILRI envisions a world where all people have access to enough food and livelihood options to fulfill their potential. ILRI’s mission is to improve food and nutritional security and to reduce poverty in developing countries through research for efficient, safe and sustainable use of livestock, ‘ensuring better lives through livestock’.

Diana Brandes-van Dorresteijn is a staff member in ILRI’s Capacity Development Unit.