The words being spilled over the hunger crisis in Niger are rising to a torrent. Media attention and consequent growing concern over soaring levels of child malnutrition finally made the crisis register on the world’s conscience. In July, as babies were shown succumbing to malnutrition, respiratory and other infectious diseases (malaria, diarrhoea) that attend the malnourished young, Niger virtually overnight became, in the words of an emergency advisor with Save the Children UK, ‘sexy'. It had been difficult until then (22 July), she said, to get international donors to dip into their pockets for Niger, a country that had not hit the headlines for drought and famine since 1985. ‘Niger is sexy now’, she said. ‘Children are dying.’ We’re now fed daily images of matchstick thin children with swollen bellies and yellow hair; of cattle carcasses littering pasturelands and roadsides, where the beasts have lain down on the sandy soils to die; of men and families and whole villages roaming the countryside with their remaining animal stock in search of work or food; and of hungry families feeding themselves on boiled grass, acacia leaves and rats. These images are signs of the country's nutritional distress.

To those of us in the over-fed developed world, they are dramatic signs. To most of the developing world’s rain-fed dryland farmers, however, such images are commonplace towards the end of the annual dry season. The story behind the famine footage in Niger is that forced fasting and weight loss, dependence on wild foods, migration, transhumance, liquidation of livestock assets, and early death of people as well as animals – particularly among the young and old – remain the cornerstone of traditional seasonal coping strategies of Niger and other drylands of the developing world. That such annual suffering and untimely death is commonplace among the world’s one billion people living in ‘absolute poverty’, defined by American economist Jeffrey Sachs as ‘the poverty that kills’, is a story itself, one that surely deserves the world's attention as much as Niger's current crisis does.

Although Niger is a country that ‘works’ on many levels, including the daily courage and stamina of its 12.9 million people, whose life expectancy is just 46 years, levels of infant mortality are high even in good years, with 3 out of 10 children dying before they reach the age of 5 from poverty, malnutrition and disease. In the 1990s it was estimated that over 32 percent of Niger’s children were stunted (half of them severely), over 15 percent wasted and over 36 percent underweight. Beyond a shortage of food, factors contributing to the country’s rising malnutrition rates include water shortages, poor water quality, an inability to pay for medical services, poor sanitation conditions and inappropriate child-care practices.

The media are calling Niger’s crisis a ‘famine’ or ‘starvation’. MSF (Doctors without Borders) is calling it a ‘severe nutritional crisis’. The United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) calls it a ‘complex emergency’. FEWS NET, a research-based famine warning service financed with United States assistance, speaks of the ‘locally severe, but non-famine nature of the crisis’. Whatever we call this food crisis, it should not be happening and it is not a temporary emergency. As FEWS NET remarks, ‘It is the predictable and inevitable result of inadequately addressed chronic poverty. Although the willingness of much of the world to address these 'famine' conditions in Niger is appropriate and welcome, without a similar commitment and prolonged attention to addressing the chronic issues that are at the heart of the current localized crises, the same problems will re-occur again soon.’

The Hunger Crisis  After months of repeated pleas from the United Nations, international aid began in July to pour into this vast arid and semi-arid and landlocked West African nation, ranked by the United Nations to be the second poorest in the world. Niger is now at the biggest impact of last year’s reduced grain, pasture and fodder yields, brought about by the biggest locust invasion of the last 15 years followed by a premature end to the rainy season. Crop and livestock farmers in Maradi, Tillabery, Zinder, and Tahoua – four departments bordering Nigeria in the south – are suffering the most. In villages here, household granaries and fodder stocks are low or empty, cereal prices are skyrocketing (they are now 75-80 percent above the average for the last five years), and livestock prices are plummeting (the cereal purchasing power for livestock-dependent households in agro-pastoral zones is only 25 percent of what it was a year ago).

After months of repeated pleas from the United Nations, international aid began in July to pour into this vast arid and semi-arid and landlocked West African nation, ranked by the United Nations to be the second poorest in the world. Niger is now at the biggest impact of last year’s reduced grain, pasture and fodder yields, brought about by the biggest locust invasion of the last 15 years followed by a premature end to the rainy season. Crop and livestock farmers in Maradi, Tillabery, Zinder, and Tahoua – four departments bordering Nigeria in the south – are suffering the most. In villages here, household granaries and fodder stocks are low or empty, cereal prices are skyrocketing (they are now 75-80 percent above the average for the last five years), and livestock prices are plummeting (the cereal purchasing power for livestock-dependent households in agro-pastoral zones is only 25 percent of what it was a year ago).

Populations have migrated out of the most vulnerable zones and are consuming wild food. One child out of five under the age of five is moderately malnourished and at risk of becoming severely so in the near future if not assisted. Moderate malnutrition is estimated between 13.4 and 19.4 percent, severe malnutrition between 2.4 and 2.9 percent in the most severely affected areas, with rates similar to those of the worst conflict zones and emergencies in the world. As many as 150,000 under 5-year-old children are affected by severe malnutrition among the estimated 800,000 malnourished children nationwide.

Jan Egeland, the UN Emergency Relief Coordinator, told reporters in July that several thousand children had undoubtedly perished this year for lack of food. An April 2005 joint food security assessment by the Niger Government, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), WFP and FEWS NET estimated that 2.4 million of the 3.6 million people living in agropastoral areas were highly vulnerable to food insecurity. Of those, 1.2 million were judged to require some level of food aid. The latest estimate is that 874,000 persons face extreme food insecurity conditions and need free food. This number could grow in the next six weeks as pastoralists return north with their remaining livestock.

Although some press reports indicate that from 150,000 infants to 3.5 million people are threatened by starvation in Niger, FEWS NET argues that there is no basis to expect that starvation is a likely outcome for these numbers of infants or people. ‘Children will likely die from malnourishment but a substantial proportion is probably dying from conditions related to poor water quality, or other non-food related problems.’ FEWS NET reports that although the current food security crisis in Niger is serious, it affects far fewer people than current crises in Ethiopia, Somalia, Zimbabwe and Sudan (Darfur and Northern Bahr El Gazal). The situation in Niger is on par with that found in eastern Chad (in both the refugee camps and among local populations near the camps), and much more severe than those currently found in Mali and Mauritania.

The Hunger Season  Hunger is an annual event in Niger, where some 82 percent of the population rely on subsistence farming and cattle rearing and only 15 percent of the land is suitable for arable farming. Beyond a little irrigation along the Niger River, most farmers are at the mercy of the rains. Food shortages lasting several months are nothing new. The annual hunger season starts after the millet is planted, at the beginning of the rains in June, and lasts through October, when it’s harvested. Last year’s double whammy of a locust plague followed by poor rains reduced not only millet harvests but also pastures, which feed the country’s livestock, the lifeblood of Niger’s farmers as well as herders. So the hunger season this year has been longer and more intense than normal, putting many people, along with their livelihoods and livestock, over the edge. Niger’s nutritional crisis is likely to deepen still further in the run up to the next harvest. Rural households traditionally help close the annual hunger gap by selling a few animals to buy enough grain to survive until the next millet harvest, in October. This strategy is not working this year. Too many animals are flooding the market, sending livestock prices down, and rising prices for scarce local grain are beyond the reach of poor farmers surviving on less than US$1 a day. Farm households have exported their young men to work as far away as Libya and Algeria and nomads are competing with farmers for scarce resources as they move their herds around looking for fodder. FEWS NET has published the following crisis indicators about the crisis in Niger:

Hunger is an annual event in Niger, where some 82 percent of the population rely on subsistence farming and cattle rearing and only 15 percent of the land is suitable for arable farming. Beyond a little irrigation along the Niger River, most farmers are at the mercy of the rains. Food shortages lasting several months are nothing new. The annual hunger season starts after the millet is planted, at the beginning of the rains in June, and lasts through October, when it’s harvested. Last year’s double whammy of a locust plague followed by poor rains reduced not only millet harvests but also pastures, which feed the country’s livestock, the lifeblood of Niger’s farmers as well as herders. So the hunger season this year has been longer and more intense than normal, putting many people, along with their livelihoods and livestock, over the edge. Niger’s nutritional crisis is likely to deepen still further in the run up to the next harvest. Rural households traditionally help close the annual hunger gap by selling a few animals to buy enough grain to survive until the next millet harvest, in October. This strategy is not working this year. Too many animals are flooding the market, sending livestock prices down, and rising prices for scarce local grain are beyond the reach of poor farmers surviving on less than US$1 a day. Farm households have exported their young men to work as far away as Libya and Algeria and nomads are competing with farmers for scarce resources as they move their herds around looking for fodder. FEWS NET has published the following crisis indicators about the crisis in Niger:

-

Unprecedented high food prices.

-

Scarcity of local foodstuffs.

-

Collapse of livestock prices.

-

Exodus/migration of entire households to neighboring countries in search of new employment.

-

Accelerated use of unsustainable survival strategies, liquidation of livestock, household assets and excessive felling of trees in fragile environments.

-

Malnutrition rates continue to climb.

The Bad News/Good News

The bad news is that in the short-term, malnutrition rates, especially for children, are likely to continue to deteriorate, even if this year’s rains continue to be good. Admissions are rising at therapeutic feeding centres and it is estimated that fewer than one malnourished person in ten makes it to one of the centres. In addition, the rainy season increases the prevalence of malaria and diarrhoeal diseases, which typically increase the risk of severe malnutrition among children. The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) in July doubled its Niger appeal and warned that it would soon raise it again. Less publicized food crises await to be properly addressed in other countries of the Sahel, the semi-arid strip south of the Sahara desert, such as Mali, Mauritania and Burkina Faso.

The good news is that the current rainy season has gotten off to a very good start in Niger. FEWS NET reports that farmers have been able to plant early; according to the Niger Government’s estimates, 92 percent of the area expected to be under cultivation had been planted by June 15 compared to the 65 percent that is normal for this time of year. The favourable rains are improving pastures, although animal conditions will not rebound immediately. FEWS NET reports that cereal prices in other parts of the Sahel are beginning to fall and those in Niger will likely do the same. Prices for livestock should soon improve with good pasture conditions. The maize harvest is underway in Nigeria, Benin, Ghana, and Ivory Coast, and supplies of imported maize from those countries should soon be arriving in Niger. This will bring lower overall cereal prices.

The national body in Niger in charge of coordinating risk reduction, prevention and response activities to mitigate and manage food crises (Dispositif National de Prévention et de Gestion des Crises Alimentaires – DNPGCA and Cellule Crise Alimentaire of the Prime Minister’s Cabinet – CCA) has so far promoted subsidized sales, cereal banks, food for work and loans of cereals to be reimbursed after the upcoming harvest in October. Since mid-July, the Government has been distributing free food to specific targets in the most critical areas while continuing to subsidize sales in less critical areas. New partners are settling in Niger and/or boosting their capacities: French Red Cross, Spanish Red Cross, Norwegian Red Cross, Qatari Red Crescent, IFRC, Save the Children US, Islamic Relief, Oxfam UK, Concern, Réunir, MSF/Switzerland. Development partners are stretching their ongoing programs to emergency response activities: World Vision, Care, Africare, CRS, Caritas, Oxfam Québec. These Christian, Muslim and secular humanitarian actors are implementing a range of activities in the most affected area of Niger’s southern agro-pastoral zone, where most of the population is concentrated, with the objective to save lives, to protect agricultural production tools/livelihoods and livestock and to promote the 2005 agricultural campaign.

Immediate Needs  FEWS NET recommends the main focus of additional, immediate, assistance be:

FEWS NET recommends the main focus of additional, immediate, assistance be:

-

an augmentation of supplemental feeding for children under five;

-

additional support for Niger’s free food distributions;

-

provision of emergency animal fodder and livestock nutritional supplements;

-

assistance with sanitation and potable water (in areas with the highest malnutrition); and

-

seeds for second season cropping, especially short cycle beans.

On 4 August, the UN raised its emergency flash appeal to almost $81 million and the WFP reported that if assistance were not provided quickly, it expects to see a massive liquidation of property and livestock with a severe impact on the current agricultural season.

Long-term Needs

Emergency assistance is not enough. More research and development resources should be spent to address Niger’s chronic food insecurity. Observers say projects aiming to address the root cause of the food crisis, which is poverty, are being diverted to support emergency efforts when the situation calls for close links between relief, development and research activities. Only such links will ensure that humanitarian programs do not inhibit longer term research and development efforts from addressing the underlying causes of poverty. Serious analysis shows that hunger can be conquered and at a modest cost compared to the benefits. The case for making agriculture a priority sector for aid to Niger – where agricultural production accounts for 39 percent of GDP – is overwhelming. ‘The least funding so far is for agricultural programmes’, Jan Egeland has said, ‘which I regret because those are the programmes that can get people out of this,’ explaining that people are now slaughtering or selling their cattle used for breeding.

The case for supporting livestock development in Niger – where livestock products make up one of just two main exports and 82 percent of the population practice agro-pastoral subsistence farming – is also overwhelming. ‘The hunger crisis in Niger is difficult to assess because it is “patchy”,’ says Bruno Gerard, an ILRI partner scientist based outside Niamey and working for the last 14 years working for ILRI’s sister institute, the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT). ‘That and other issues that must be addressed to resolve Niger’s chronic food insecurity are largely researchable issues,’ he says. Gerard manages a large project with 10 partners building research-based ‘decision-support systems’ to help farmers improve their marketing, soil fertility and other strategies. ‘This is not a hopeless country’, says Gerard. ‘Traditional options are simply not working well. The real opportunities here are in finding ways to intensify the traditional mixed crop-and-livestock farming systems for greater productivity and sustainability. And that’s just what we’re doing with ILRI and other scientific partners.’

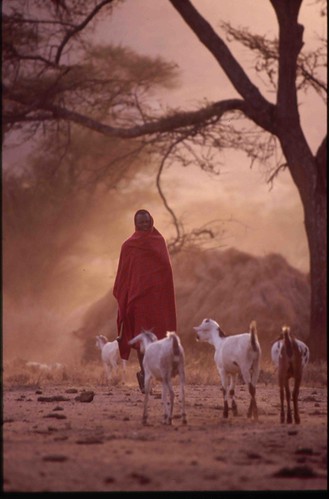

The Livestock Crisis  Nomadic herdsmen, whose starving cattle and donkeys have begun dying in large numbers, are at even greater risk than crop farmers. Humanitarian workers reckon it will take them at least two years to rebuild their herds. The limited availability of pasture and of fodder is endangering livestock. Niger’s fodder deficit in pastoral areas in 2004 was 154 percent greater than the 2000 deficit, and at 4.6 tons, the largest fodder deficit in Niger’s history. One-third of this deficit was caused by locusts and two-thirds by the 2004 drought. Fodder remains very expensive. Cows, sheep, goats and camels, which represent the ‘saving accounts’ of agro-pastoralists and pastoralists, are typically meagre and are being sold at dramatically low prices. The monetary value of livestock compared to the equivalent in cereals has decreased between 42 and 55 percent. High cereal prices and falling animal prices in the most affected pastoral and agro-pastoral areas, have led to some households having to liquidate assets in the face of these harsh terms of trade.

Nomadic herdsmen, whose starving cattle and donkeys have begun dying in large numbers, are at even greater risk than crop farmers. Humanitarian workers reckon it will take them at least two years to rebuild their herds. The limited availability of pasture and of fodder is endangering livestock. Niger’s fodder deficit in pastoral areas in 2004 was 154 percent greater than the 2000 deficit, and at 4.6 tons, the largest fodder deficit in Niger’s history. One-third of this deficit was caused by locusts and two-thirds by the 2004 drought. Fodder remains very expensive. Cows, sheep, goats and camels, which represent the ‘saving accounts’ of agro-pastoralists and pastoralists, are typically meagre and are being sold at dramatically low prices. The monetary value of livestock compared to the equivalent in cereals has decreased between 42 and 55 percent. High cereal prices and falling animal prices in the most affected pastoral and agro-pastoral areas, have led to some households having to liquidate assets in the face of these harsh terms of trade.

In worst cases, cows are being sold for US$10. Dakoro, Filingué and Ouallam are the worst affected zones for livestock. Pastoralists and agro-pastoralists began moving their animals south towards the coast earlier than normal to graze on the residue of harvested crops. While this preserves the herds, pastoralist households, especially women and children who normally remain in Niger, will be longer without meat and milk from their animals, and will have to buy more of their food by selling small animals, their assets, or their labor. This also results in larger numbers of males migrating to seek paid labour. This year's return of livestock herds from the south began with the good rains that started in May and June. There have been cases where some herds were temporarily ‘stranded’ between their northern pastures that had yet to regenerate, and the areas they were leaving in order for planting to begin. It is also noted that this year, coping capacities appear to be stretched to the limit by continuing high cereal prices that translate into poor terms of trade in selling livestock to buy cereals.

-Source: FEWS NET

ILRI and Livestock Research in Niger

|

|

ILRI has conducted livestock research for development in Niger for three decades. ILRI’s senior scientists in the country have included (in chronological order) geographer and anthropologist Matt Turner (USA), rangeland ecologist Pierre Hiernaux (France), soil scientist Mark Powell (USA), agricultural economist Tim Williams (Nigeria), animal nutritionist Salvador Fernández-Rivera (Mexico), and livestock systems specialist Augustine Ayantunde (Nigeria), the latter leads ILRI research in Niger today. Among the Nigerian support team that have worked for ILRI over these years are two technicians who have lived and worked for 15 years in ILRI’s two target villages in Fakara, an area between the Niger Valley and the Dallol Bosso, one hundred km east of Niger’s capital, Niamey. ILRI work in Fakara covers a region of over 500 sq km. Most of the images in this photo essay were obtained in Fakara in June 2005, one month before the country's hunger problem began to make news.

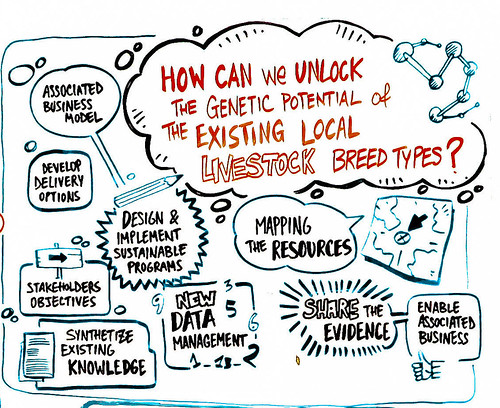

ILRI’s long-term focus in Niger is finding improved ways to integrate livestock keeping into crop farming systems to improve the Sahel’s fragile lands as well as the livelihoods of its peoples. ILRI (www.ilri.org) has conducted much of its research in Niger under the aegis of two systemwide programs of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (www.cgiar.org), which sponsors the research of ILRI and 14 other centres working to alleviate poverty in the developing world: the ILRI-convened Systemwide Livestock Programme (www.vslp.org/vslp/front_content.php) and the ICRISAT-convened Desert Margins Program (www.icrisat.org/text/partnerships/dmp/dmp.htm). In these and other projects, ILRI focuses on livestock aspects and ICRISAT on food and feed crops which, taken together, can refine the integration of crop and livestock production with triple-bottom-line benefits for people (more food), livestock (more feed) and soils (more nutrients).

ILRI’s Niger team recently conducted a project funded by USAID investigating how to improve markets for small-scale peri-urban farmers producing milk and fattening sheep (for Muslim holidays) and collaborated with America’s Wisconsin University on research to help manage conflicts between crop and livestock producers. In the scorching hot and resource-challenged Sahelian environments, where transhumance is practised as it has been for millennia, and where millet and livestock mean life and livelihood to most of the population, conflicts over increasingly scarce water and land resources are increasing.

Livestock Relief  FAO renewed on 2 August its appeal for $4 million urgently needed for veterinary services and to feed livestock, which play a key role in the livelihoods and food security of many of the most vulnerable households. ‘Livestock are crucial to agro-pastoralist families in Niger, for income as well as food,’ the Chief of FAO’s Emergency Operations Service, Fernanda Guerrieri, said. ‘The sale of livestock is often a measure of last resort, after families have already consumed all of their cereal stocks and require cash to buy food for the lean period before the next harvest. A loss of livestock or decrease in their market value can have a devastating impact on these families’ food security,’ she added. Livestock aid is needed for more than 10,000 families who have lost their animals. Without this assistance, the crisis could worsen and more food aid would be needed. The funds will be used to provide veterinary services and feed for more than 10,000 families facing severe hunger due to livestock losses.

FAO renewed on 2 August its appeal for $4 million urgently needed for veterinary services and to feed livestock, which play a key role in the livelihoods and food security of many of the most vulnerable households. ‘Livestock are crucial to agro-pastoralist families in Niger, for income as well as food,’ the Chief of FAO’s Emergency Operations Service, Fernanda Guerrieri, said. ‘The sale of livestock is often a measure of last resort, after families have already consumed all of their cereal stocks and require cash to buy food for the lean period before the next harvest. A loss of livestock or decrease in their market value can have a devastating impact on these families’ food security,’ she added. Livestock aid is needed for more than 10,000 families who have lost their animals. Without this assistance, the crisis could worsen and more food aid would be needed. The funds will be used to provide veterinary services and feed for more than 10,000 families facing severe hunger due to livestock losses.

Oxfam is helping 28,000 people by buying, for a fair price, cattle too emaciated for herders to sell. Cattle prices have been plummeting and are now 90 percent lower than they were before the crisis. Even healthy animals are fetching only a fraction of their former value. A strong bull that once went for more than $500 now sells for as little as $18. ‘Oxfam’s response is stimulating the economy by trying to use local markets,’ said Mike Delaney, Oxfam America’s director of humanitarian response. Another voucher-for-work project is linked to the cattle-buying program. Oxfam has already purchased 1,000 cows from local breeders for about $53 a head, providing people with money to feed both their families and their remaining animals. Oxfam then has the cows slaughtered in the villages and inspected by veterinarians to make sure the meat is fit for consumption. Women involved in the voucher-for-work program dry or fry the meat. Oxfam gives some of the meat to them in exchange for their work, or distributes it through the rest of the voucher program.

Bitter Ironies  Newcomers heading into Niger’s countryside find it surprisingly green. Aside from pockets of dusty scrub, healthy young foot-tall millet crops appear from one horizon to the other. Herein lies a bitter paradox. The rainy season, which gets into full swing in August, actually started well this year, in June. But this does nothing to fill the so-called hunger gap between the June planting and October harvesting. Crops may be growing, but they are of no use to anyone for another two months. New grass sprouting from sandy rangelands is just as useless to the ubiquitous herds of cattle and donkeys, for many of which the young shoots are too little too late; the animals lie down on the new green pastures and don’t get up again. Things appear deceptively fine even in the mud hut villages – where the women pound millet and the children run and play – until one takes a closer look or pays a visit to the women’s huts where the ‘silent hunger’, as its being called, has struck young children, making them too weak or ill to cry.

Newcomers heading into Niger’s countryside find it surprisingly green. Aside from pockets of dusty scrub, healthy young foot-tall millet crops appear from one horizon to the other. Herein lies a bitter paradox. The rainy season, which gets into full swing in August, actually started well this year, in June. But this does nothing to fill the so-called hunger gap between the June planting and October harvesting. Crops may be growing, but they are of no use to anyone for another two months. New grass sprouting from sandy rangelands is just as useless to the ubiquitous herds of cattle and donkeys, for many of which the young shoots are too little too late; the animals lie down on the new green pastures and don’t get up again. Things appear deceptively fine even in the mud hut villages – where the women pound millet and the children run and play – until one takes a closer look or pays a visit to the women’s huts where the ‘silent hunger’, as its being called, has struck young children, making them too weak or ill to cry.

Many villagers say they can’t afford to leave their families to take a famished child to the nearest feeding centre. They are busy ploughing and preparing their land for the next crop that will feed their household for the coming year. Even when sick, many people won’t come for treatment because they’re frightened to leave the young crops that they’re trying to nurse into life. It is a deathly bind. Top United Nations aid official Jan Egeland and aid officials have accused the international community of reacting slowly to the crisis in Niger, which was widely predicted after last year's poor harvests, and further say the slow response has greatly increased the cost of dealing with the crisis. When the first appeal was made, only $1 per day, per person would have helped solve the food crisis, the U.N. has said. Now that the situation has worsened and people are weaker, $80 will be needed per person. One reason for the delay in international response was that other events were crowding out news about the hunger in major media.

Following the worst turmoil in Darfur and the tsunami in Southeast Asia, ironically it was the G8 summit in Gleneagles, Scotland, in June, with the rock-star Live8 concerts and ‘Make Poverty History’ campaigns that attended it, that helped push the Niger crisis off world headlines. While the G8 was noisily canceling the debts of Niger and 13 other African countries, this club of the world’s most powerful nations failed to notice or even mention Niger’s hunger crisis.

The Cereal Crisis  As local cereals (millet, sorghum) have become scarce items on the market in Niger and the subregion as well as subject to speculation, prices have doubled over normal. Most warehouses are empty. Assessments undertaken by CILSS (the regional inter-governmental body responsible for Sahelian food security) found that unusually high prices for millet and sorghum in neighboring markets in Nigeria, Ghana, Benin and Ivory Coast have been drawing Sahelian grain to the south during the last few months. Outflow from Niger has been significant and a major factor in driving up prices in the agro-pastoral and pastoral zones of Niger where purchasing power is the weakest. In most years, Niger imports cereals from surplus-producing areas of its neighbors in Nigeria, Burkina Faso, and Mali. However, this year, each of these three countries imposed restrictions of exports, due to fears of famine and grain shortages, despite trade treaties that forbid that. CILSS has cautioned that overstatements of the severity of Sahelian food crises by the media, international agencies, and NGOs have had the unintended consequence of causing private traders to withhold stocks from the market, in anticipation of higher prices, or of local purchases by aid agencies, further pushing up cereal prices.

As local cereals (millet, sorghum) have become scarce items on the market in Niger and the subregion as well as subject to speculation, prices have doubled over normal. Most warehouses are empty. Assessments undertaken by CILSS (the regional inter-governmental body responsible for Sahelian food security) found that unusually high prices for millet and sorghum in neighboring markets in Nigeria, Ghana, Benin and Ivory Coast have been drawing Sahelian grain to the south during the last few months. Outflow from Niger has been significant and a major factor in driving up prices in the agro-pastoral and pastoral zones of Niger where purchasing power is the weakest. In most years, Niger imports cereals from surplus-producing areas of its neighbors in Nigeria, Burkina Faso, and Mali. However, this year, each of these three countries imposed restrictions of exports, due to fears of famine and grain shortages, despite trade treaties that forbid that. CILSS has cautioned that overstatements of the severity of Sahelian food crises by the media, international agencies, and NGOs have had the unintended consequence of causing private traders to withhold stocks from the market, in anticipation of higher prices, or of local purchases by aid agencies, further pushing up cereal prices.

These issues merit further study.  West African grain markets are generally working very well, perhaps too well. The high cereal price levels found in the Sahel are being driven by strong demand for Sahelian cereal production, and greater purchasing power in coastal West African countries. Markets in the most food-insecure zones in the Sahel (and in Niger) usually have higher cereal prices than elsewhere, due to the high costs of transporting grain to these sparsely-populated and poor areas. Although their governments are committed to open markets, high costs and infrastructure limitations do not allow Sahelian markets to efficiently collect surpluses, anticipate local and regional demand conditions, and supply foods to poor households at affordable prices. Source: FEWS NET

West African grain markets are generally working very well, perhaps too well. The high cereal price levels found in the Sahel are being driven by strong demand for Sahelian cereal production, and greater purchasing power in coastal West African countries. Markets in the most food-insecure zones in the Sahel (and in Niger) usually have higher cereal prices than elsewhere, due to the high costs of transporting grain to these sparsely-populated and poor areas. Although their governments are committed to open markets, high costs and infrastructure limitations do not allow Sahelian markets to efficiently collect surpluses, anticipate local and regional demand conditions, and supply foods to poor households at affordable prices. Source: FEWS NET

ILRI, Livestock and the Millennium Development Goals  The international community is laying the groundwork for a new, coherent and eminently feasible attack on global poverty. The focus of this effort is the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) – eight commitments drawn from the Millennium Declaration, endorsed by all member states of the United Nations in September 2000. Ranging from halving extreme poverty to halting the spread of HIV/AIDS and providing universal primary education – all by the target date of 2015 – they represent a set of simple but powerful objectives that every man and woman in the street, from New York to Nairobi to New Delhi, can easily understand and support. . . . The MDG are people-centred, time-bound and measurable. . . . Now we have a set of clear, measurable indicators, focused on basic human needs, that can provide clear benchmarks of progress – or the lack of it – both globally and on a country-by-country basis. . . . Never before have such concrete goals been formally endorsed by rich and poor countries alike. And never before have the UN, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and all the other principal arms of the international system come together behind the same set of development objectives. . . . And the MDG are achievable. – Source: Kofi Annan, Economist: The World in 2003

The international community is laying the groundwork for a new, coherent and eminently feasible attack on global poverty. The focus of this effort is the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) – eight commitments drawn from the Millennium Declaration, endorsed by all member states of the United Nations in September 2000. Ranging from halving extreme poverty to halting the spread of HIV/AIDS and providing universal primary education – all by the target date of 2015 – they represent a set of simple but powerful objectives that every man and woman in the street, from New York to Nairobi to New Delhi, can easily understand and support. . . . The MDG are people-centred, time-bound and measurable. . . . Now we have a set of clear, measurable indicators, focused on basic human needs, that can provide clear benchmarks of progress – or the lack of it – both globally and on a country-by-country basis. . . . Never before have such concrete goals been formally endorsed by rich and poor countries alike. And never before have the UN, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and all the other principal arms of the international system come together behind the same set of development objectives. . . . And the MDG are achievable. – Source: Kofi Annan, Economist: The World in 2003

The knowledge and technologies generated by ILRI and its many partners in the North and South that are conducting livestock research for development are helping to meet the United Nations Millennium Development Goals. ILRI is a non-profit-making and non-governmental organization working at the crossroads of livestock and poverty. ILRI has its headquarters in Nairobi, Kenya, and a second principal campus in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The Institute belongs to the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). This association of more than 60 governments and organizations supports a network of 15 Future Harvest agricultural research centres working to reduce poverty, hunger and environmental degradation in developing countries. The co-sponsors of the CGIAR are the World Bank, the UNDP, FAO and the International Fund for Agricultural Development.