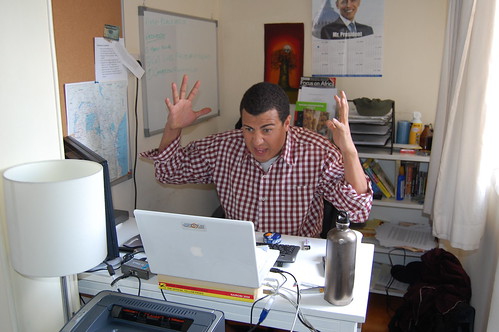

Jeff Haskins at a conference of the Global Forum for Rural Advisory Services in Nairobi in Nov 2011 (photo credit: Eric McGaw).

We at the Kenya-based International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) and at CGIAR and other institutions working for agricultural development in poor countries are still reeling from the news that our chief media strategist, writer, consultant and friend for the last six years, American Jeff Haskins, of Burness Communications, died of a heart attack at the Kenya coast early Saturday morning on 14 Jul 2012.

Just ten days before that, Jeff had sent out a news release he had shepherded through at least a dozen drafts about a new ILRI report that maps the likely hotspots of poverty and diseases shared by people and animals. This, the latest media campaign Jeff and his colleagues at Burness had waged with ILRI, was in some respects ILRI’s most successful yet. Our news ran in hundreds of print and online media and blogs across six continents, 20 countries and 10 languages, from the most prestigious scientific journals (Nature, Science, The Lancet), to popular science media (New Scientist, The Scientist), to broadcast heavyweights (BBC, Deutsche Welle, Voice of America), to top-tier print newspapers (Globe and Mail, Le Monde, New York Times, Sydney Morning Herald, Times of India) and magazines (Der Spiegel, Wired), to some of the biggest wire services (Bloomberg, Reuters, Xinhua), to some of the hottest blogs (Fast Company’s Co.EXIST, Gizmodo). In a cruel irony Jeff would have appreciated, we have continued to get alerts of new press clippings throughout these first ten days of mourning his loss of life, the ILRI news being published on the very morning of his death in the New York Times Sunday Review, with the headline and an accompanying illustration appearing on the front page of the Times, above the fold.

Jeff had turned 32 the week before he died. He had just celebrated his fourth wedding anniversary with Meredith Braden, with whom he’d been together since he was sixteen. He and Meredith had just moved from their work-efficient apartment at Nairobi’s Yaya Centre into a nearby house with a small garden. He had just started growing (and eating) his own vegetables. He had just bought a BMW touring motorcycle. He had just announced that he and Meredith were expecting their first child.

He was going to buy land in Kenya and settle and raise his children here. He was going to start escaping on weekend motorcycle safaris with Meredith and friends. He was going to find new ways to reach the new social as well as traditional media. He was going to learn how to combine his fine still images with sound in powerful photofilm formats.

He was going to be big. As big as his outsized heart. His outsized commitments. His outsized passion and energy.

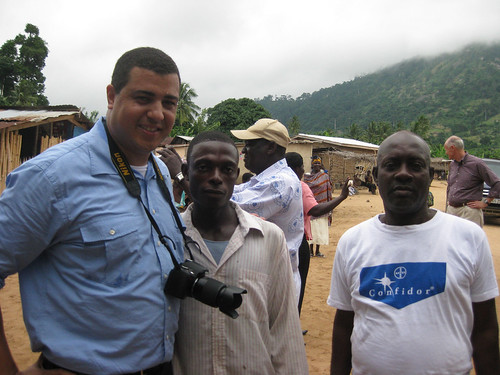

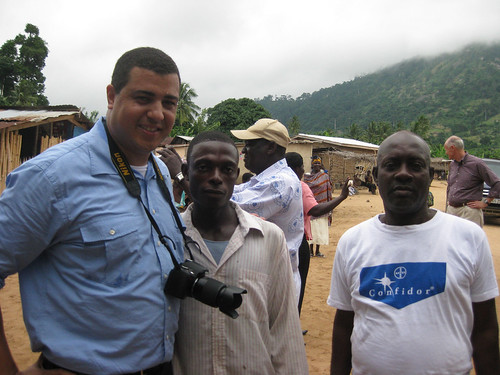

Jeff and a friend, ‘Do it’, by Jeff.

A hyper-active, hyper-productive journalist working 24/7 for all seasons and many centres of CGIAR (the mothership of ILRI and 14 other institutes working for global food-security), Jeff worked in Africa for six years for Burness Communications, a US-based public relations company, setting up their first Africa office and then becoming director of BurnessAfrica.

Voice of America journalist Cathy Majtenyi and media specialist Jeff Haskins, of Burness Communications, at the CGIAR News Briefing on ‘Research Options for Mitigating Drought-induced Food Crises,’ 1 Sep 2011 (photo credit: ILRI/Susan MacMillan).

In this job, Jeff crisscrossed the globe, working with whoever and whatever would advance his cause. Over time he became a veritable one-man farmers’ almanac of even the most arcane aspects of research on developing-country agriculture. In Nairobi he worked with the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), the CGIAR Gender & Diversity Program, the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), the Kenya Agricultural Research Institute (KARI) and the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF). He worked with the Seattle-based Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF), the Montpellier-based CGIAR Consortium and the Copenhagen-based CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). He worked with the Cornell University-based Borlaug Global Rust Initiative and the Accra-based Forum for Agricultural Research in Africa (FARA). He worked with the Paris-based International Council for Science, and with the Cali-based International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), the Ibadan-based International Institute for Tropical Agriculture (IITA), the Colombo-based CGIAR Challenge Program on Water and Food (CPWF), and the Rome-based Global Crop Diversity Trust.

Jeff’s media badges, by Jeff.

To cover their stories of cassava, maize, potato, bean, millet, rice, wheat, groundnut, livestock, land, water, wildlife, policy, women, he travelled more in his short life than most of us. From Lagos to Ibadan. Cotonou to Monrovia, Accra to Dakar. Limuru to Marsabit. Bangkok to Chiang Mai. London to Paris. Rio to Rwanda.

He covered agro-dealers in Uganda, black-eyed peas in Senegal, logging in Liberia, legumes in Lamu, grain markets in Abuja, maize in Malawi, dairies in Ol Kalou, seed suppliers in Malawi, ministerial dialogues in Ouagadougou, press conferences in Nairobi, foresters in Yaoundé, yam festivals in southeast Nigeria.

Jeff Haskins with Kofi Annan in Ghana (photo credit: Eric McGaw).

He hung out with journalists and farmers, with film-makers and drivers, as well as with the luminaries of our agricultural development world—people like Nobel Laureate Norman Borlaug, father of the Green Revolution, Kofi Annan of the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa, Monty Jones of the Forum for a Green Revolution in Africa, Cary Fowler of the Global Crop Diversity Trust, and Carlos Seré of the International Livestock Research Institute.

Jeff in Nsawam, eastern Ghana, by Jeff.

Moving from place to place, Eldoret to Moiben, Samburu to Soy, he attended farmer association meetings, school outings, installations of weather stations and launches of insurance schemes. He photographed and choreographed media coverage of a world cowpea conference in Dakar and starving cattle outside Nairobi, Hilary Clinton’s visit to Nairobi and the African Women’s Agricultural Research Development program, and the opening of the ‘doomsday’ seed vault in Svalbard, deep in the frozen wastes of the Arctic Circle.

Jeff on the road, by Jeff.

With his ever-inquisitive, ever-roving mind, he was always pushing, pushing, pushing against our institutional agenda with his questions. What was the future of livestock, he would ask. Why weren’t we (ILRI) doing more with camels to help pastoral herders cope with climate change? What did we think of the guinea pig as a dinner staple? Is rabbit meat the next big thing? Could we replace cows with artificial lab-grown meat? (Those who have been on the receipt-end of a Jeff Haskins-led media campaign will recognize the onslaught of interest and queries.)

From the food price crises to devastating droughts and crop failures to plagues of disease to malnourished children to water scarcity to the marginalization of women to lousy markets and worse weather to catastrophic livestock losses, Jeff was there, talking, probing, organizing, photographing, texting on his iPhone, writing on his iPad. Usually all at once.

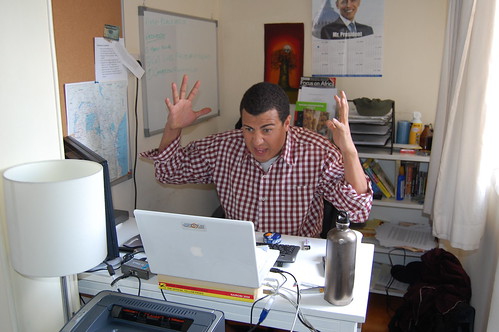

Jeff at work, by Jeff.

He did all this with the urgency of a war correspondent needing to get stuff captured, and captured fast. And yet, unlike many war correspondents, he was full not of doom but of cautious optimism. And a kind of irrepressible energy that inspired hope even in dire situations.

Like many of Jeff’s clients, I work for a research institute that remains largely ignorant of the manic ways and means of major media. Jeff understood that. He knew that scientists were a cautious bunch, tending (compared to himself) to move at glacial speeds. So he tried hard—with only some success—to keep a lid on his impatience as his interest built inexorably in a barrage of emails he would start sending one’s inbox the moment he hatched an idea for a possible new story.

Jeff at Ras Nungwi Beach, Zanzibar, by Jeff.

Jeff’s appetite for life was big. His interests wide. His friendships deep. Somehow, he always made time for building relationships, for mentoring the young and learning from experts he admired. In his non-existent spare time, he managed visits to the Great Wall of China, the canals of Amsterdam, the streets of Paris, the art of Rome, the wildebeest migration in the Mara. He liked to retreat at the end of hectic projects to the balmy beaches of Diani, on the south coast of Kenya, which is where, at the break of a tropical dawn ten days ago, he suffered fatal cardiac arrest.

‘Wonderwoman and me’, Jeff and Meredith, by Jeff.

He packed in a lot in his 31 short years, from teenage rock guitarist to loving family man to science reporter to global journalist advocate for African agriculture.

Jeff had everything to look forward to. That he died in the midst of building an uncommonly big life, enriched by close family and friends, a mission to serve others, an impossible job he loved and did impossibly well, and a driving passion to excel, is heartening. And heart-breaking.

Like many of the people he worked with and for, Jeff Haskins died long before his time.

Those of us he has left behind could do worse than learn from his legacy what we might do with the works and days that remain to us.

25 major ILRI news releases produced over the past five years by ILRI and Africa media specialist Jeff Haskins, of Burness Communications

2007

(1) Sep: A ‘livestock meltdown’ is occurring as farm animals face extinction

(2) Nov: Cutting-edge breed technologies help Kenyans capitalize on dairy boom

2008

(3) Apr: Rising milk and meat prices bring threats and opportunities

(4) Sep: Uniting human and animal health in Africa

2009

(5) Apr: Drastic declines in wildlife in Kenya’s Masai Mara

(6) May: Conference promotes US$150-billion African produce market

(7) Jun: Climate change could ruin 1m sq km of African staple crop farming

(8) Oct: American TV show ’60 Minutes’ features ILRI research in Masai Mara

(9) Nov: Climate change to create losers as well as winners in East Africa

(10) Dec: Producing more livestock foods with fewer greenhouse gas emissions

2010

(11) Jan: Insuring Kenya’s pastoralists against drought

(12) Feb: New investments need to support mixed crop-livestock farmers

(13) Jul: Losses of Africa’s native livestock threaten food supplies

(14) Sep: Better pastures and breeds could reduce carbon ‘hoofprint’

(15) Nov: Four-plus degree world will create widespread farm failure in Africa

2011

(16) Jan: Mixed farmers on extensive frontier critical to global food security

(17) Feb: Livestock boom risks aggravating animals plagues

(18) Feb: Livestock one of three ways to feed the growing world—Economist

(19) May: Scientists identify livestock genes responsible for resisting disease

(20) Jun: Mapping hotspots of climate change and food insecurity

(21) Jun: East Africa, Middle East prevent livestock diseases from disrupting trade

(22) Jun: Livestock and climate change: Towards credible figures

(23) Aug: Invest in pastoralism to combat drought in East Africa

2012

(24) Mar: Farmers must be linked to markets to combat Africa’s food woes

(25) Jul: Hotspots mapped of new and old human-animal disease outbreaks

20 major ILRI opinion pieces developed over the past five years by ILRI and Africa media specialist Jeff Haskins, of Burness Communications

2007

(1) Is eating meat worse for the environment than driving? Science in Africa

(2) Another inconvenient truth, letter to The New York Times

2008

(3) When worlds collide: Those who eat too much—and those who eat too little, ILRI News Blog

(4) Rising world food prices, CGIAR media roundtable

2009

(5) Livestock and climate change: Towards credible figures,

letter to the International Herald Tribune and The New York Times

(6) Demonizing livestock hurts one billion poor, unpublished letter to The New York Times

(7) Renewing African agriculture, Science Alert

(8) Putting food on the climate change table: Time for climate negotiators to put meat on the bones of the next agreement, ScienceAfrica

(9) No simple solution to livestock and climate change, SciDevNet

(10) Balancing the global need for meat, BBC News viewpoint

2010

(11) Should we eat less meat to increase food security?: Vicki Hird and John McDermott disagree, British Science Association

(12) Livestock diversity needs genebanks too, SciDevNet

(13) Animal farm: Ending poverty by keeping cows on the farm, World Food Prize Symposium

(14) Backing smallholder farmers today could prevent the food crises of tomorrow, Guardian’s Poverty Matters Blog

2011

(15) Animal farming and human health are intimately linked, Guardian’s Poverty Matters Blog

(16) A famine-proof world requires investment in farm research, Des Moines Register

(17) Investment in pastoralists could help combat east Africa food crisis, Guardian’s Global Development Blog

2012

(18) Bring markets to farmers’ doorstep: Jimmy Smith and Namanga Ngongi say agricultural markets could be the engines of Africa’s development, The Star (Kenya)

(19) Turning defeat into new destiny—Going beyond food aid in the Horn of Africa, ILRI News Blog

(20) More on getting credible figures for livestock emissions of greenhouse gases, ILRI News Blog

Jeff, by Jeff.

.jpg!Blog.jpg)

.jpg!Blog.jpg)

.jpg!Blog.jpg)

.jpg!Blog.jpg)

.jpg!Blog.jpg)

.jpg!Blog.jpg)

.jpg!Large.jpg)