Opening keynote slide presentation by Jimmy Smith, director general of ILRI, at the 22nd International Grasslands Congress, held in Sydney, Australia, 16 September 2013 (credit: ILRI).

This is the first of a two-part article.

The world’s small-scale farmers and livestock keepers, both relatively under-appreciated in global food security discussions and agenda till now, can be a large part of the solution, rather than a problem, to feeding the world sustainably to 2050.

This was the message today (Mon 16 September 2013) of Jimmy Smith, an animal scientist, food security specialist and director general of the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI). Smith is in Australia to give the keynote address to the 22nd International Grassland Congress being held in Sydney 15–19 September 2013. This global forum is being attended by 1000 delegates from more than 60 countries.

In his presentation, Feeding the world in 2050: Trade-offs, synergies and tough choices for the livestock sector, Smith gave an overview of the global food security challenge and argued that smallholder animal agriculture is key to addressing it.

1: We need lots more food

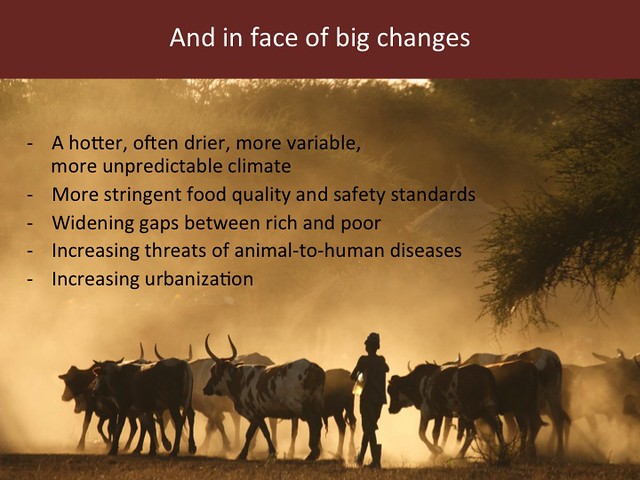

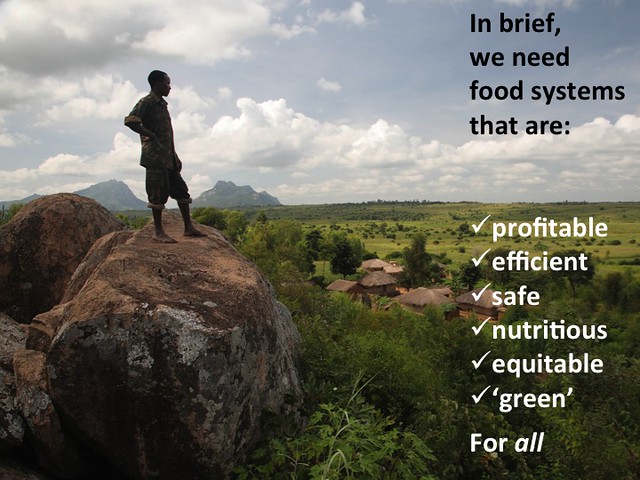

‘Producing sufficient quantity and quality of food for nearly 10 billion people represents a huge challenge’, Jimmy Smith said. ‘We need lots more food in the next four decades and we need to produce it profitably, efficiently, safely, equitably and without destroying the environment.’

The world’s sub-optimal diets

‘It’s a shocking indictment of the global food system’, Smith said, ‘that in the 21st century most of the world’s population have sub-optimal diets’.

• 870 million go to bed hungry

• 2 billion are vulnerable to food insecurity

• 1 billion have diets that don’t meet their nutritional requirements

• 1 billion suffer the effects of over-consumption

While all of these are problems we must address, I believe most of us would agree that there is no moral equivalence between those who make poor choices of food and those who have no food choices.— Jimmy Smith

2: The role of small-scale livestock production

Unknown to most people, Smith said, is just how much food is produced by smallholders. Some 500 million smallholders support more than 2 billion people. In South Asia, for example, more than 80% of farms are less than 2 hectares in size. In sub-Saharan Africa, smallholders contribute more than 80% of livestock production.

Unknown to most people, Smith said, is just how much food is produced by smallholders. Some 500 million smallholders support more than 2 billion people. In South Asia, for example, more than 80% of farms are less than 2 hectares in size. In sub-Saharan Africa, smallholders contribute more than 80% of livestock production. Also unknown to many is just how competitive smallholders can be.

In India, at least 70% of the milk produced comes from smallholders and India is now the largest dairy producer in the world. In East Africa, Kenya’s 1 million smallholders keep the largest dairy herd in Africa (larger than South Africa); Uganda has lowest-cost milk producers globally; small-scale Kenyan dairy producers get above-normal profits of 19−28% in addition to non-market benefits (insurance, manure, traction) of a further 16−21%. And ILRI and partner scientists have shown that Kenya’s small- and large-scale poultry and dairy producers have the same levels of efficiencies and profits.

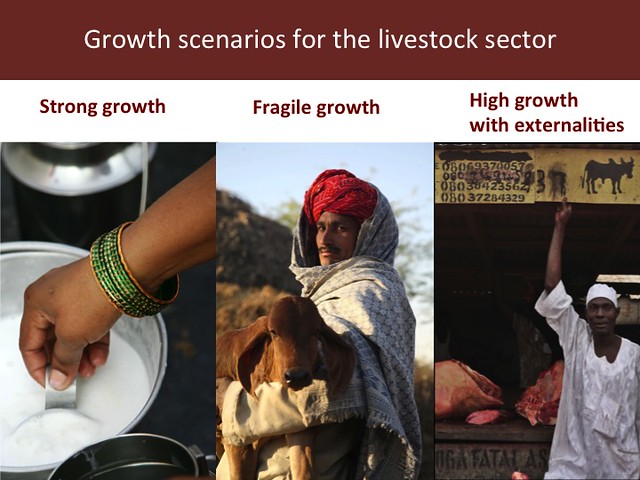

ILRI and other global partners recognize three major trajectories livestock systems are moving along as they develop, Smith reported. These are:

Strong growth

Where good market access and

increasing productivity provide opportunities for continued smallholder participation.

Fragile growth

Where remoteness, marginal land resources or agro-climatic vulnerability restrict intensification.

High growth with externalities

Where fast-changing livestock systems can damage the environment and human health.

Each of these, he said, presents different research and development challenges for poverty, food security, health and nutrition, and the environment.

Part two of this article is published here.

About Jimmy Smith

Jimmy Smith, a Canadian, is director general of the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), a position he assumed on 1 October 2011. Before joining ILRI, he worked for the World Bank, in Washington, DC, where he led the Bank’s Global Livestock Portfolio. Before joining the World Bank, he held senior positions at the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA). Still earlier in his career, Smith worked at ILRI and its predecessor, the International Livestock Centre for Africa (ILCA), where he served as the institute’s regional representative for West Africa and subsequently managed the ILRI-led Systemwide Livestock Programme of the CGIAR, an association of 10 CGIAR centres working at the crop-livestock interface. Before his decade of work at ILCA/ILRI, Smith held senior positions in the Caribbean Agricultural Research and Development Institute (CARDI). Smith was born in Guyana, in the Caribbean, where he was raised on a small mixed crop-and-livestock farm. He is a graduate of the University of Illinois at Urban-Champaign, USA, where he completed a PhD in animal sciences. He is widely published, with more than 100 publications, including papers in refereed journals, book chapters, policy papers and edited proceedings.

About ILRI

The International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) works with partners worldwide to enhance the roles that livestock play in food security and poverty alleviation, principally in Africa and Asia. The outcomes of these research partnerships help people in developing countries keep their farm animals alive and productive, increase and sustain their livestock and farm productivity, find profitable markets for their animal products, and reduce the risk of livestock-related diseases. ILRI is a member of the CGIAR Consortium, a global research partnership of 15 centres working with many partners for a food-secure future.

About the 22nd International Grasslands Congress

The program and other information about the 22nd International Grasslands Congress, ‘Revitalising grasslands to sustain our communities’, is online here.

Thanks for sharing this. I think in the future we are going to see a rise in resilient small scale farming as the flaws inherent in the ‘bigger is better’ model start emerging.