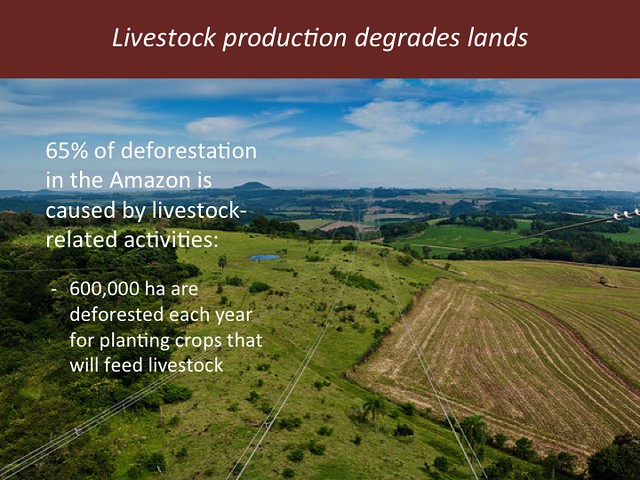

Most Kenyan farmers listen to the radio to learn how to farm better but are not receiving the information they need (photo credit: Flickr/Internews Network).

Radio is still the dominant media channel used by Kenya’s small-scale farmers wanting to learn new techniques to improve their farming methods. But farmers say they’re still not receiving most of the agricultural information they badly need.

Findings of a 2012 study of over 600 small-scale farm households spread across high- to low-yield agricultural regions of Kenya in Nakuru, Nyanza, Nyeri, Machakos, Makueni and Webuye show that farmers receive mostly basic ‘how to’ and technical information; despite its modest usefulness, this kind of information is not enough to enable these Kenyan farmers to improve their food production levels or practices.

Selected findings from this study were shared in a presentation, ‘Shortcomings in communications on agricultural knowledge transfer’, made by Christoph Spurk, a media researcher, at a seminar on 17 Oct 2013 at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), in Nairobi, Kenya.

‘Over 75 per cent of the households we reviewed practised mixed crop-and-livestock farming, with an average of 4–6 people in each household occupying 1–3 acres of land. Over half of those we interviewed were women’, said Spurk, who is also an agricultural economist and a professor at the Zurich University of Applied Sciences, Institute of Applied Media Studies.

‘One of our key findings’, says Spurk, ‘was that government extension services are still the “most trusted source” of agricultural information for most farmers, even though many of these services are “difficult to reach and less available than expected”.’

At the same time, the study found significant gaps between the agricultural information farmers would like to receive and what they actually get through different communication channels.

‘The farmers are receiving mostly technical agricultural information even though they prefer information on markets, improving incomes and fighting farm-related diseases’, said Spurk. ‘They also said most of the information they get is presented in simplified top-down “how-to” formats rather than in detailed formats that lay out the different options available to them.’

According to the study’s findings, radio is used by 95% of the households. Even though two-thirds of the households also have access to mobile phones, only 11% of mobile phone owners use these devices to access to agricultural applications such as ‘iCow’, which registered farmers use to receive information on, for example, optimal feeding regimes and gestation cycles for their particular cows.

Although most of the farmers interviewed reported that they regularly listen to vernacular radio stations, nearly all them said their favourite source of information is other farmers and family members. Just under half of the farmers (44%) said government extension services were their most trusted source of information. In terms of sources of detailed farming information, farmers reported preferring first to listen to other farmers, second to take part in field visits and only third to listen to radio programs.

Spurk believes findings from this study highlight a need for greater integration between radio and extension services to better reach small-scale farmers and a need to provide farmers with the kind of information that empowers them in their own decision-making.

Note: In October 2012, this blog reported on a study by Farm Radio International in Africa, which showed that participatory radio campaigns that use local languages, allow farmer participation and highlight tested and available technologies help in hastening the adoption of new technologies by small-scale farmers in Africa.

Download a PDF version of the study report:

http://www.zhaw.ch/fileadmin/user_upload/linguistik/_Institute_und_Zentren/IAM/PDFS/News/final_report_Kenya_agri_communication_IAM_MMU_01.pdf