At the World Food Prize ceremony (12 October 2010) and Borlaug Dialogue (13–15 October 2010) in Des Moines, Iowa, last week, issues surrounding small-scale livestock enterprises received a rare dose of major attention.

First, Jo Luck, president of Heifer International, an American livestock-based non-governmental humanitarian organization, received the World Food Prize, considered the ‘Nobel Prize of agriculture’. Only the third woman to be so honoured, Jo Luck shared this year’s World Food Prize with David Beckmann, head of Bread for the World, another American-based NGO.

Following the award ceremonies, the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) and other key livestock-for-development organizations took part in a special ‘Livestock in Smallholder Agriculture Symposium’.

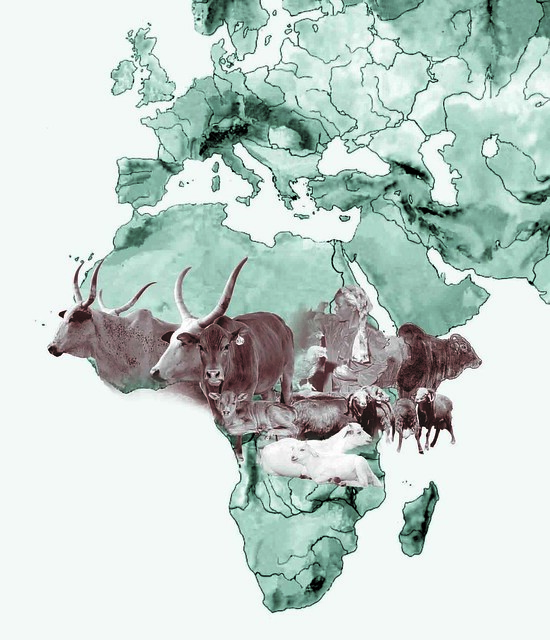

Carlos Seré, director general of the Africa-based ILRI, was a member of a panel moderated by Alice Pell, vice provost at Cornell University. Seré provided context for the high-level discussions about the importance smallholder animal agriculture. ‘Feeding the next 2 to 3 billion people,’ he said, ‘will require the sustainable inte¬nsification of the world’s “mixed” farming systems, which combine livestock raising with crop production. ‘

Seré pointed out the need to find smarter ways for the world’s small-scale farmers to integrate crops, animals and trees on their farms. He explained how better livestock feeding systems can reduce methane and other greenhouse gas emissions from livestock enterprises in both developing and developed countries. And he described how stover and other wastes of crop production are increasingly being used by small-scale farmers in poor countries as supplementary feed for their animal stock, which subsist largely on grass and planted forages rather than grains.

‘Livestock bring cash into the small farming system,’ Seré said. ‘They constitute the motor that links farmers to urban producers, and they give millions of people who own no land at all the means by which to earn an income.’

Seré also pointed out the need for the private sector to find ways to engage with the ‘bottom billion’ of poor livestock farmers. By creating or joining farm cooperatives, food producer companies and contract farming schemes, he said, these dispersed smallholders become subjects of interest to the private sector. Once aggregated in such societies, small farmers become attractive to businesses looking to provide the agricultural sector with livestock services and other inputs, as well as processing plants and distribution channels for crop and animal products.

‘Smallholder farmers can be very competitive,’ Seré said. ‘Agribusiness would profit from thinking up imaginative ways to do business with them. Agri- and other businesses wanting to work broadly in rural sub-Saharan Africa, for example, all find themselves working with smallholder livestock farmers.’

Another panelist, Deepack Tikku, chairman of the National Dairy Development Board Dairy Services in India, described how his country surpassed the United States as the world’s largest milk producer.

‘Our model is not one of mass production but production by the masses,’ he said. He describe the food, income and gender distribution gains that India has made in increasing its milk production, almost all from smallholders, from 20 million tonnes in 1970 to 112 million tonnes today.

Thad Simons, chief executive officer of Novus International, focused his panel remarks on eggs, ‘the original superfood’. ’Eggs are one of the best ways to deliver protein to consumers at affordable costs,’ Simons said. ‘No other food provides as much nutrition in so few calories at such a low cost.’ Novus has begun an information campaign—www.eggtruth.com—to increase consumption of eggs, particularly among mothers and young children, to help families stay financially as well as physically fit.

Christie Peacock, chief executive of the non-governmental organization FARM-Africa, asked policymakers to pay more attention to helping smallholder farmers acquire livestock. ‘It’s my passionate belief that livestock are the fastest route out of poverty,’ Peacock said. ‘My experience in Ethiopia taught me that when crops fail, having one or two goats enables families to survive. Without animals, many families in such circumstances have to go on food aid.’

Peacock also argued that the commonplace views in the North about the environmental damage caused by livestock are among the biggest threats to livestock development in the South, where domesticated animals continue to play many central roles in the livelihoods of the poor. ‘Obviously, there are hotspots of livestock-related environmental damage, such as those in the Amazon and Southeast Asia, that we must address’ Peacock said. ‘But what we must not do is to let the life chances of the world’s poor livestock keepers be compromised by Northern prejudices against livestock.’

The agricultural development ‘luminaries’ attending the World Food Prize and Borlaug Dialogue in Iowa this year included, in addition to those named above, HE Kofi Annan, Nobel Laureate, former secretary-general of the United Nations and current chairman of the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa; Howard Buffett, president of the Howard G Buffet Foundation (and farm and livestock ranch owner); Marco Ferroni, executive director of the Syngenta Foundation, Christopher Flavin, president of the Worldwatch Institute; Kamal El-Kheshen, president of the African Development Bank; Matt Kistler, senior vice-president of marketing for Walmart; Gregory Page, chairman and chief executive officer of Cargill; Amrita Patel, chairman of India’s National Dairy Development Board; Prabhu Pingali, deputy director of Agricultural Development, and Jeff Raikes, chief executive officer, at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation; Rajiv Shah, administrator of the United States Agency for International Development; MS Swaminathan, chairman of the MS Swaminathan Foundation; and Tom Vilsack, secretary of the United States Department of Agriculture.