If, as the popular science saying goes, we can understand only what we can measure, what shall we say about what we can locate on a map? Is that, too, a foundation for real understanding, or is mapping more like taxonomy, more critical to scientific knowledge (categorization) than to scientific understanding (causation)?

A group of some 80 international and developing-country experts in the use of geographical information systems (GIS), remote sensing and other high-tech tools developed in the field of what was once innocently called ‘geography’ met in Nairobi last week (8–12 June 2010) to see if they couldn’t, by working together better, speed work to reduce world poverty, hunger and environmental degradation. (Oddly, this gathering of people all about ‘location’ tend to use a forest of acronyms — GIS, ArcGIA, CSI, ESRI, ICT-KM, AGCommons, CIARD, CGMap — in which the casual visitor is likely to get lost.)

The participants at this meeting, called the ‘Africa Agricultural GIS Week’, aimed to find ways to offer more cohesive support to the international community that is working to help communities and nations climb out of poverty through sustainable agriculture.

The world’s big agricultural problems – too little food to feed the 6-plus and growing billions of people on the planet, too extractive (unsustainable) ways of producing food, too little new land left to put to food production, too few viable agricultural markets serving the poor, too high food prices for the urban poor, too extreme and variable climates for sustaining rural agricultural livelihoods – appear to be fast closing in on us. Our global agricultural problems are of an increasingly connected and complex nature. Most experts agree that silver-bullet solutions are not the answer. We must tackle these problems holistically or, in the jargon of agricultural science, from a systems-based perspective.

And that, perhaps, is where these high-tech geographers can most help us navigate the future of small-scale food production.

At the opening of this Week’s events, held at the Nairobi campus of the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), Vish Nene, a molecular biologist who directs ILRI’s Biotechnology Theme, spoke on behalf of ILRI’s director general, Carlos Seré, who was on mission travel abroad. Nene welcomed Kenya’s Assistant Minister of Agriculture and MP, Hon Japhet Mbiuki, who gave a keynote speech on behalf of Kenya’s Minister for Agriculture, Hon Dr Sally Kosgei.

Nene said that ILRI was particularly pleased to be hosting this meeting, as it has a long track record in the use of GIS in its research portfolio, having developed a GIS Unit first some 22 years ago and being a leader today in large-scale, fine-resolution, mapping of the intersection of small-scale livestock enterprises and global poverty.

The second day of the Week, An Notenbaert, a GIS expert at ILRI, gave the participants an overview of what ILRI has been doing in the area of geospatial research, and what particular kinds of geospatial services and expertise ILRI could offer new ‘mega-programs’ of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR).

Notenbaert sketched two of ILRI’s research projects that require a ‘spatial’ foundation.

Protecting remote herders with their first drought-related livestock insurance

The first ILRI project Notenbaert described is one that this year is piloting ‘index-based livestock insurance’ for remote Kenyan livestock herders. This project, she said, is all about managing risks in dry, harsh lands, where most people’s livelihoods still depend on livestock herding. Because traditional livestock insurance is impractical for the dispersed herding populations of Kenya’s northern frontier, ILRI researchers initiated a study on the feasibility of using information not about the number of livestock deaths in droughts over the years, but rather an indicator associated with such drought-related animal deaths. ‘We are using satellite images of vegetation of the region to come up with a livestock mortality index,’ she said. ‘This is quite a neat application of remote sensing data.’

The pilot project was launched in Kenya’s Marsabit District in January 2010. Livestock owners in the district have bought insurance premiums that will pay out not when their animals die (which would require a logistically complex and expensive procedure to verify animal deaths), but rather when satellite images show that livestock forage has dipped below a predetermined threshold, with the likely result of many animals dying.

Down-scaling climate projections for more useful information for policymakers

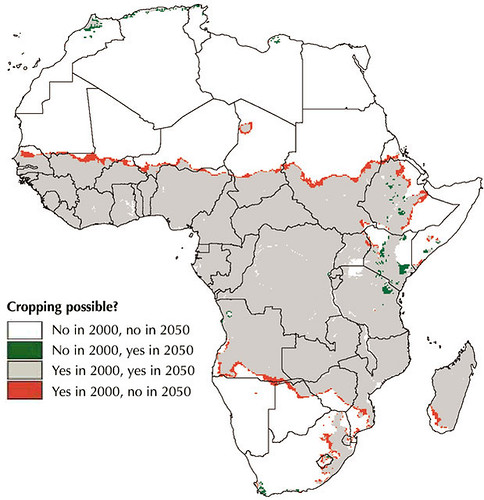

The second ILRI project Notenbaert described to the assembled group of spatial experts is working to make more local, and thus more useful, assessments of the impacts of climate change on poor communities in the tropics.

Little information, for example, is available on climate change in East Africa, whether at country or local levels. While a projected increase in rainfall in East Africa to 2080, extending into the Horn of Africa, is robust across the ensemble of Global Circulation Models available, other work suggests that climate models have probably underestimated the warming impacts of the Indian Ocean and thus may well be over-estimating rainfall in East Africa during the present century.

In 2006, ILRI researchers estimated changes in aggregate monthly values for temperature and precipitation. Possible future long-term monthly climate normals for rainfall, daily temperature and daily temperature diurnal range were derived by down-scaling the outputs of Global Circulation Models to WorldClim v1.3 climate grids at a resolution of 18 square kilometres. Outputs from several Global Circulation Models and scenarios made by the Special Report on Emissions Scenarios (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2000) were used to derive climate normals for 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, 2020, 2025 and 2030 using the down-scaling methodology described in 2003 by ILRI researchers. Although the figures derived for Kenya correspond with findings of long-term wetting, the ILRI researchers also found the regional variations in precipitation to be large, with the coastal region likely to become drier, for example, while Kenya’s highlands and northern frontier are likely to become wetter.

For more information, see:

Index-based Livestock Insurance

Climate Projection Data Download

AGCommons: Location-specific information services for agriculture

Coherence in Information for Agricultural Research for Development

The Swedish-funded BioInnovate Africa program today launched a call for concept notes on “Adapting to Climate Change in Agriculture and the Environment in Eastern Africa.”

The Swedish-funded BioInnovate Africa program today launched a call for concept notes on “Adapting to Climate Change in Agriculture and the Environment in Eastern Africa.”