Who eats better, pastoral children in mobile herding or settled communities? (answer: mobile). Which kind of tropical lands are among those most at risk of being grabbed by outsiders for development? (rangelands). Are pastoral women benefitting at all from recent changes in pastoral livelihoods? (yes). Which region in the world has the largest concentration of camel herds in the the world? (Horn of Africa). Where are camel export opportunities the greatest? (Kenya/Ethiopa borderlands). Is the growth of ‘town camels and milk villages’ in the Somali region of Ethiopia largely the result of one man’s (desperate) innovation? (yes). Which is the more productive dryland livestock system, ranching or pastoralism? (pastoralism). Is irrigation involving pastoralists new? (no). Are we missing opportunities to make irrigated agriculture a valuable alternative or additional livelihoods to pastoralism? (perhaps).

The answers to these and other fascinating questions most of us will never have thought to even ask are found in a new book, Pastoralism and Development in Africa: Dynamic Change at the Margins, edited by Andy Catley, of the Feinstein International Center, at Tufts University; Jeremy Lind, of the Institute of Development Studies at the University of Sussex and Future Agricultures Consortium; and Ian Scoones, of the Institute of Development Studies, the STEPS Centre and the Future Agricultures Consortium. Published in 2012, it includes a chapter by scientists at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI): Climate change in sub-Saharan Africa: What consequences for pastoralism?

Thirty-six experts in pastoral development update us on what’s so in pastoral development in the Greater Horn of Africa, highlighting innovation and entrepreneurialism, cooperation and networking and diverse approaches rarely in line with standard development prescriptions. The book highlights diverse pathways of development, going beyond the standard ‘aid’ and ‘disaster’ narratives. The book’s editors argue that ‘by making the margins the centre of our thinking, a different view of future pathways emerges’. Contributions to the book were originally presented at an international conference on The Future of Pastoralism in Africa, held at ILRI’s campus in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in Mar 2011.

Here are a few of the book’s ‘unstandard’ ways of looking at pastoralism.

‘Overall, mainstream pastoral development is a litany of failure. . . . Pastoral borderlands are . . . beyond the reach of the state, and so the development industry. · Perhaps no other livelihood system has suffered more from biased language and narratives than pastoralism. . . . Hidden in these narratives also are political agendas that perceive mobile pastoralism as a security and political threat to the state, and, therefore, in need of controlling or eliminating. · To avoid the Malthusian label, or simply out of ignorance, many social scientists have neglected the important implications of demographic trends in pastoral areas. . . . Some of the fastest growing towns in Kenya are in pastoralist districts. · Local demand for education is consistently high among pastoralists, a pattern that was not the case even 10–15 years ago. · It seems feasible . . . to propose a pastoral livestock and meat trade value approaching US$1 billion for the Horn in 2010. · The past dominant livestock practice characterized as “traditional mobile pastoralism” is increasingly rare. . . . The creation of a relatively elite commercial class within pastoral societies is occurring at a rapid pace in some areas. · . . . [P]astoral lands are vulnerable to being grabbed. On a scale never before envisioned, the most valued pastoral lands are being acquired through state allocation or purchase . . . . The Tana Delta sits at the precipice of an unprecedented transformation as a range of investors seek to acquire large tracts of land to produce food and biofuels and extract minerals, often at the expense of pastoralists’ access to key resources. . . . A notable facet of changing livelihoods in the Tana Delta is the increasingly important role of women in the diversifying economy, a trend seen elsewhere in the region. . . . Until now, pastoralists have been mostly unsuccessful at challenging proposed land deals through the Kenyan courts. · The shift from a breeding herd to a trading herd is perhaps the biggest shift in Maasai pastoralism. · Although drought is a perennial risk to pastoralist livelihoods, an emerging concern is securing access to high value fodder and other resources to support herds, in areas where rangelands are becoming increasingly fragmented due to capture of key resource sites. · During the 2009–2011 drought in the Horn of Africa, several hundred pastoralists who participated in an Index-Based Livestock Insurance (IBLI) scheme in northern Kenya received cash payments. · Despite its many challenges, mobile pastoralism will continue in low-rainfall rangelands throughout the Horn for the simple reason that a more viable, alternative land use system for these areas has not been found. . . . But the nature of pastoralism in 2030 will be very different than today in 2012. . . .’

One of the book’s chapters is on Climate change in sub-Saharan Africa: What consequences for pastoralism? It was written by ILRI’s Polly Ericksen (USA), whose broad expertise includes food systems, ecosystem services and adaptations to climate change by poor agricultural and pastoral societies; and her ILRI colleagues Jan de Leeuw (Netherlands), an ecologist specializing in rangelands (who has since moved to ILRI’s sister Nairobi CGIAR centre, the World Agroforestry Centre); Mohammed Said (Kenyan), an ecologist specializing in remote sensing and community mapping; Philip Thornton (UK) and Mario Herrero (Costa Rica), agricultural systems analysts who focus on the impacts of climate and other changes on the world’s poor countries and communities; and An Notenbaert (Belgium), a land use planner and spatial analyst.

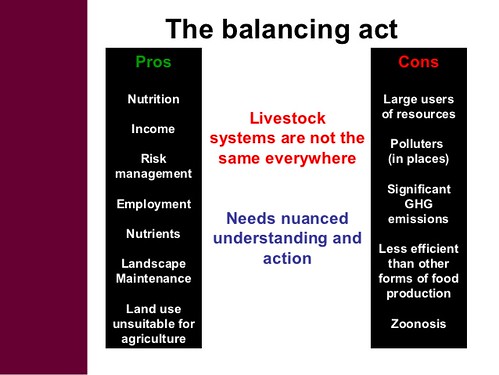

The ILRI scientists argue that if we’re going to find ways to adapt to climate change, we’re going to need to learn from pastoralists — who, after all, are demonstrably supreme managers of highly variable climates in addition to rapidly changing social, economic and political contexts — about how to make sustainable and profitable, if cyclical and opportunistic, use of increasingly scarce, temporally erratic and spatially scattered water, land, forage and other natural resources.

In important respects, pastoral people are at the forefront of responses to climate change, given their experience managing high climate variability over the centuries. Insights from pastoral systems are critical for generating wider lessons for climate adaptation responses.’

What scientists don’t know about climate change in these and other drylands, they warn, is much, much greater than what we do know. So:

The key question is how to make choices today given uncertainties of the future.’

Because ‘the more arid a pastoral environment, the less predictable the rainfall’, and because ‘vegetation growth closely follows rainfall amount, frequency and duration, . . . the primary production of rangelands is variable in time and space’, with the primary driver of this variability in livestock production in pastoral areas being the availability or scarcity of forages for feeding herds of ruminant animals (e.g., cattle, sheep, goats, camels). In severe or prolonged droughts, forage and water scarcity become a lethal combination, killing animals en masse. The authors quote former ILRI scientist David Ndedianye, a Maasai from the Kitengela rangelands in Nairobi’s backyard, and other ILRI colleagues who report in a 2011 paper on pastoral mobility that pastoral livestock losses in a 2005 drought in the Horn were between 14 and 43% in southern Kenya and as high as 80% in a drought devastating the same region in 2009. It may take four or five years for a herd to recover after a major drought.

Maps of a flip in temperatures above 30 degrees C. Left: Threshold 4 — maximum temperature flips to greater than 30°C. Right: Threshold 5 — maximum temperature in the growing season flips to greater than 30°C. Map credit: Polly Ericksen et al., Mapping hotspots of climate change and food insecurity in the global tropics, CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), 2011.

Evidence from a range of modelling efforts was used by the authors to calculate places in the global tropics where maximum temperatures are predicted to flip from less than 30 degrees C to greater than 30 degrees C by 2050. This temperature threshold is a limit for a number of staple crops, including maize beans and groundnut. Heat stress also affects grass and livestock productivity. Large areas in East African may undergo this flip, according to these models, although the authors warn that these predictions remain highly uncertain.

Thornton and Herrero in a background paper to the World Bank’s 2010 World Development Report investigated the impacts of increased drought frequency on livestock herd dynamics in Kenya’s Kajiado District. ‘Their results indicate that drought every five years keeps the herds stable as it allows sufficient time for the herds to re-establish. A once in three year drought interval by contrast drives livestock density to lower levels . . . . Hence, if there is a greater frequency of drought under climate change, this might have a lasting impact on stocking density, and the productivity of pastoral livestock systems.

The results were extrapolated to all arid and semi-arid districts in Kenya and estimated that 1.8 million animals could be lost by 2030 due to increased drought frequency, with a combined value of US$630 million due to losses in animals, milk and meat production. . . .’

In the face of changes in climate (historical and current), many pastoralists will change the species of animals they keep, or change the composition of the species in their herds. In the space of three decades (between 1997/8 and 2005–10) in Kenya, for example, the ratio of shoats (sheep and goats) to cattle kept increased significantly. Goats, as well as camels, are more drought tolerant than cattle, and also prefer browse to grasses.

Such changes in species mix and distribution will have important implications for overall livestock productivity and nutrition, as well as milk production.’

While change is and always has been fundamental to pastoralist livelihood strategies, much more—and much more rapid and diverse—change is now sweeping the Horn and many of the other drylands of the world, with local population explosions and increasing rangeland fragmentation and civil conflicts coming on top of climate and other global changes whose nature remains highly uncertain. New threats are appearing, as well as new opportunities.

While the ILRI team argues that we can and should look to pastoralist cultures, strategies and innovations for insights into how the wider world can adapt better to climate change, they also say that ‘development at the margins’ is going to be successful only where pastoralists, climate modellers and other scientists work together:

. . . [A]daptation and response strategies in increasingly variable environments must emerge from grounded local experience and knowledge, as well as be informed by increasingly sophisticated [climate] modeling efforts.’

Support for the conference and book came from the UK Department for International Development, the United States Agency for International Development in Ethiopia, and CORDAID. Purchase the book from Routledge (USD44.96 for the paperback edition): Pastoralism and Development in Africa: Dynamic Change at the Margins, first issued in paperback 2012, edited by Andy Catley, Jeremy Lind and Ian Scoones, Oxon, UK, and New York: Routledge and Earthscan, 328 pages. You’ll find parts of the book available on Google books here.

To read the ILRI chapter—Climate change in sub-Saharan Africa: What consequences for pastoralism?, by Polly Ericksen, Jan de Leeuw, Philip Thornton, Mohammed Said, Mario Herrero and An Notenbaert—contact ILRI communications officer Jane Gitau at j.w.gitau [at] cgiar.org.