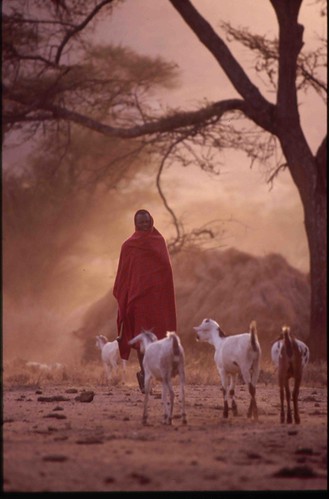

Peter Little, co-author of the timely new publication, Risk and Social Change in an African Rural Economy: Livelihoods in Pastoralist Communities, and leader of a recent review of ILRI’s pastoral research (photo credit: Emory University).

Risk and Social Change in an African Rural Economy: Livelihoods in Pastoralist Communities is a new book published by research partners John McPeak and Peter Little, of a Livestock-Climate Change initiative of the Collaborative Research Support Program (Livestock-CC-CRSP).

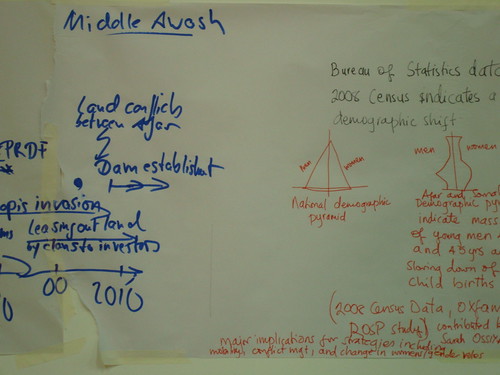

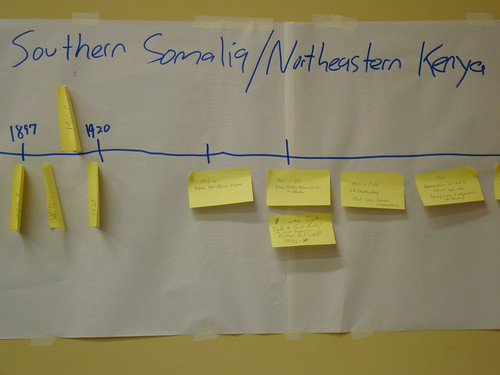

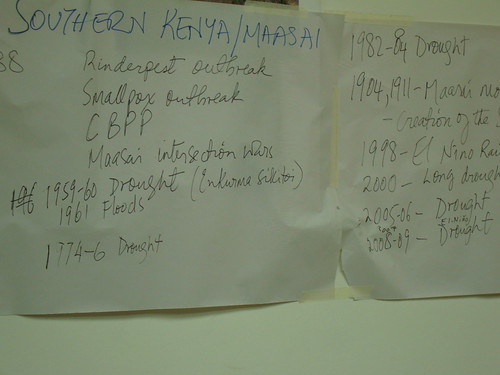

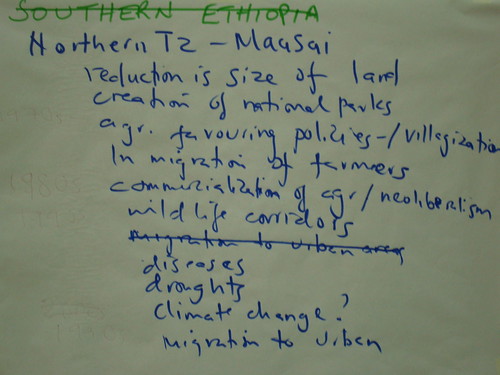

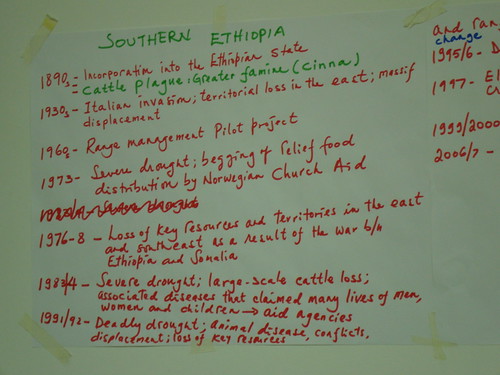

The book summarizes the results of a multi-year interdisciplinary research project in pastoral areas of Kenya and Ethiopia. The authors describe the ecology and social context in which pastoralism takes place, with a particular focus on the risks that confront people living in these drylands, and how these risks are often triggered by highly variable rainfall conditions, a symptom of climate change.

The authors go on to describe the livelihood strategies employed by pastoralists in these areas, with a focus on how well-being is tied to access to livestock and the cash economy. They conclude that the future development activities need to be built on the foundation of the livestock economy, instead of seeking to replace it.

Those wanting expert advice on how to help pastoralists suffering from a great drought afflicting the Horn of Africa today either to rebuild their shattered lives when the next rains come or to help them prevent such a catastrophe from occurring again in this region will profit from reading this book, which concludes with how development activities ‘are assessed by people in the area and what activities they prioritize for the future.’

John McPeak is an associate professor and vice-chair in the Department of Public Administration in the Maxwell School of Syracuse University; he is a member of a Livestock-CC-CRSP project in Mali and leads another project in Senegal. Peter Little is professor of anthropology and director of a Program in Development Studies at Emory University and leads a Livestock-CC-CRSP project in Ethiopia and Kenya. This project is known as CHAINS, which stands for ‘Climate variability, pastoralism, and commodity chains in Ethiopia and Kenya.’ The CRSP initiatives are funded by the United States Agency for International Development.

Co-author Peter Little headed a recent review of pastoral research at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), based in Nairobi, Kenya, and Addis ababa, Ethiopia, two countries whose dryland pastoralists are suffering from the current drought in the Horn of Africa. Little concurs with many others when he says that, ‘The famine in Somalia is an unfortunate intersection of failed rain, politics and conflict.’

The following is a description of the book from Routledge.

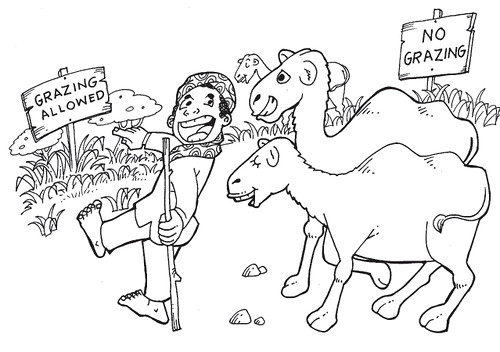

‘Pastoralists’ role in contemporary Africa typically goes underappreciated and misunderstood by development agencies, external observers, and policymakers.

Yet arid and semi-arid lands, which are used predominantly for extensive livestock grazing, comprise nearly half of the continent’s land mass, while a substantial proportion of national economies are based on pastoralist activities.

‘Pastoralists use these drylands to generate income for themselves through the use of livestock and for the coffers of national trade and revenue agencies. They are frequently among the continent’s most contested and lawless regions, providing sanctuary to armed rebel groups and exposing residents to widespread insecurity and destructive violence.

The continent’s millions of pastoralists thus inhabit some of Africa’s harshest and most remote, but also most ecologically, economically, and politically important regions.

‘This study summarizes the findings of a multi-year interdisciplinary research project in pastoral areas of Kenya and Ethiopia. The cultures and ecology of these areas are described, with a particular focus on the myriad risks that confront people living in these drylands, and how these risks are often triggered by highly variable rainfall conditions. The authors examine the markets used by residents of these areas to sell livestock and livestock products and purchase consumer goods before turning to an analysis of evolving livelihood strategies. Furthermore, they focus on how well-being is conditioned upon access to livestock and access to the cash economy, gender patterns within households and the history of development activities in the area. The book concludes with a report on how these activities are assessed by people in the area and what activities they prioritize for the future.

‘Policy in pastoral areas is often formulated on the basis of assumptions and stereotypes, without adequate empirical foundations. This book provides evidence on livelihood strategies being followed in pastoral areas, and investigates patterns in decision making and well being. It indicates the importance of livestock to the livelihoods of people in these areas, and identifies the critical and widespread importance of access to the cash economy, concluding that future development activities need to be built on the foundation of the livestock economy, instead of seeking to replace it.’

Get the book—Risk and Social Change in an African Rural Economy: Livelihoods in Pastoralist Communities, by John G McPeak, Peter D Little, Cheryl R Doss, published 28 Jul 2011, by Routledge, 206 pages—from Routledge online.