Kenya: drought leaves dead and dying animals in northern Kenya (photo on Flickr by Brendan Cox / Oxfam).

Humanitarian organizations are bracing themselves for the the task of addressing the unfolding crisis in the drought-stricken Horn of Africa, where the rains have failed for two consecutive years and the next rainy season is not expected until September, at the earliest.

The BBC reports that in Kenya’s Dadaab refugee camp, to which starving Somali’s are fleeing at a rate of some 1000 a day, ‘at a makeshift cattle market in the middle of the refugee camp, herdsmen are trying to sell off what little livestock they have left.

‘But no-one wants to buy the cattle and goats on sale here, for the chances are that very soon they will be dead.

‘There is nowhere for them to graze: the pastures here are parched and arid, and it has barely rained for two years running.

‘”I’m selling my cattle at knock-down prices,” said one man. “I’m practically giving them away.”

‘Not far away, the landscape is littered with the carcasses of dead animals.

‘In this part of the world, livestock are everything: they represent a family’s entire assets, capital, savings and income. When the animals die, it frequently means the humans do as well.’

Read the full article at the BBC: Horn of Africa drought: Vision of hell, 8 Jul 2011.

All organizations involved in supporting these livestock-keeping peoples of the Horn are passionate about not only saving the most vulnerable members of these pastoral communities today, but also about finding long-term solutions to recurring drought in this region. Those solutions necessarily rely on an evidence base provided by scientists, particularly livestock researchers.

Four recent research reports published by the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), based in Nairobi, Kenya, noted and linked to below, assess the effectiveness of past drought interventions in Kenya’s northern drylands and offer tools for better management of the region’s drought cycles.

(1) Leeuw, Jan de; Ericksen, P.; Gitau, J.; Zwaagstra, L.; MacMillan, S. Jul 2011. ILRI research charts ways to better livestock-related drought interventions in Kenya’s drylands. ILRI Policy Brief.

(2) Johnson, N. and Wambile, A. (eds). 2011. The impacts of the Arid Lands Resource Management Project (ALRMPII) on livelihoods and vulnerability in the arid and semi-arid lands of Kenya. ILRI Research Report 25. Nairobi, Kenya: ILRI.

From the abstract: ‘There is an urgent need for new approaches and effective models for managing risk and promoting sustainable development in arid and semi-arid lands (ASALs), especially in the face of climate change and increasing frequency of drought in many areas. This study assesses the impacts of the Arid Lands Resource Management Project (ALRMPII), a community-based drought management initiative implemented in 28 arid and semi-arid districts in Kenya from 2003 to 2010. The project sought to improve the effectiveness of emergency drought response while at the same time reducing vulnerability, empowering local communities, and raising the profile of ASALs in national policies and institutions. . . .’

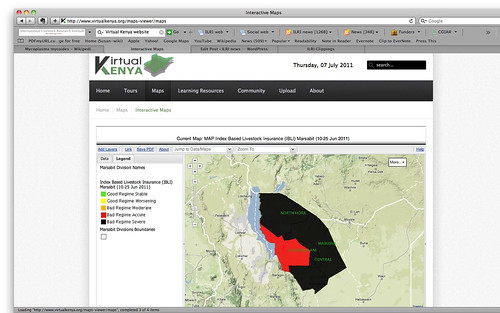

(3) Ericksen, P., Leeuw, J. de and Quiros, C. 2010. Livestock drought management tool. Final report for project submitted by ILRI to the FAO Sub-Regional Emergency and Rehabilitation Officer for East and Central Africa 10 December 2010. Nairobi, Kenya: ILRI.

From the abstract: In August 2010, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) sub-Regional Emergency Office for Eastern and Central Africa (REOA) contracted the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) to develop a proto-type “Livestock Drought Management” (LDM) decision support tool for use by a range of emergency and relief planners and practitioners throughout the region. The tool, which is still conceptual rather than operational, links the concepts of Drought Cycle Management (DCM) with the best practice in livestock-related interventions throughout all phases of a drought, from normal through the alert and emergency stages to recovery. The tool uses data to indicate the severity of the drought (hazard) and the ability of livestock to survive the drought (sensitivity). . . . The hazard data has currently been parameterized for Kenya, but can be used in any of the REOA countries. At the moment, the missing item is good-quality data for sensitivity. Additionally, experts did not agree on how to define the phase of the drought cycle. The tool requires pilot testing in a few local areas before it can be rolled out everywhere.

(4) Zwaagstra, L., Sharif, Z., Wambile, A., de Leeuw, J., Said, M.Y., Johnson, N., Njuki, J., Ericksen, P. and Herrero, M., 2010. An assessment of the response to the 2008 2009 drought in Kenya. A report to the European Union Delegation to the Republic of Kenya. Nairobi, Kenya: ILRI.

In early 2010, ILRI scientists reviewed responses to Kenya’s 2008–2009 drought in six arid and semi-arid districts of the country. The authors reviewed 474 livestock-based interventions and came up with the following conclusions, recommendations and lessons regarding the drought management intervention cycle, among others.

The Early Warning Bulletins

Conclusion: . . . To allow sufficient time to scale up livestock based interventions . . . have early warning based on indicators that precede the deterioration of livestock condition, such as rainfall estimates or the greenness of rangeland detected from satellite imagery. . . . Recommendation: Include a separate early warning message in the EWB specifically geared towards triggering interventions aiming at livestock. . . . [Harmonize] procedures used among districts for such a livestock early warning system.

Timing of interventions

Conclusion: The timing of several of the interventions, notably destocking, was too late while vaccination was implemented during an inappropriate phase of the drought management cycle. . . . Recommendation: Strengthen capacity to plan the implementation of each intervention type in view of the phase of the drought management cycle.

Effectiveness and appropriateness of interventions

1 Water tankering and borehole support

Conclusion: Water tankering and support to boreholes were considered effective [but] repair to water infrastructure can be done in periods of reduced stress. . . . Recommendation: Maintain boreholes and other water infrastructure during periods of reduced stress in order to increase drought preparedness.

2 Destocking

Conclusion: An estimated 16,996 TLU [tropical livestock units] were purchased or slaughtered in response to the drought in the 6 study districts. This is higher than the 9,857 TLU were purchased in 2000/1 in 10 districts (Aklilu and Wekesa 2001), but far below what would have been needed. Slaughter destocking interventions . . . were considered more effective than commercial destocking . . . . Recommendation: Make use of existing commercial livestock marketing infrastructure and on site slaughtering to destock during drought. To achieve optimal impact, initiate these interventions early on in the drought management cycle. See chapter 7 and annex 5 commercial destocking workshop section for further recommendations.

3 Health

Conclusion: Over 5.7 million animals were reached by health interventions between July 2008 and December 2009. De-worming was considered effective and appropriate, while vaccination was not. Recommendation: Increase de-worming during drought as it keeps animals in better condition for longer. Restrict vaccination at middle or end drought as it might create mortality with animals in poor body condition

4 Forage and supplements

Conclusion: The provision of feed was far too little and poorly coordinated, overall it was considered among the least effective interventions. . . . It is worthwhile to consider developing hay production and fodder markets locally. Recommendation: Promote initiatives to develop local hay production, fodder markets and strategic fodder reserves.

5 Migration and peace-building

Conclusion: Peace building interventions were generally considered effective; 30% more animals migrated in 2008/9 than in 2000/1. Disease problems reduced effectiveness, which suggests that interventions around these issues should be part of future migrations. Recommendation: Access to disputed land as part of pastoral mobility remains paramount in their coping strategy and more effective means to support this are required. This includes GoK commitment to play their role but specific interventions can be designed in the short and medium term to alleviate this problem as well.

6 Livelihood implications

Conclusion: . . . Interventions that build on and support local livelihoods and link to longer term development are better than purely emergency ones. Recommendation: Build on and strengthen rather than undermine local institution, livelihood strategies and coping strategies.

7 Community involvement

Conclusion: Despite recommendations from past assessments, few interventions involved the community in design or implementation. Those that did tended to have better outcomes than those that did not. Recommendation: Involve communities before the drought in the design of drought contingency plans.

8 Triggering of interventions

Conclusion: As yet there are no agreed upon triggers for the release of contingency funds. Furthermore access to these funds is often delayed due treasury related constraints. Recommendation: The drought contingency plans should be regularly updated and contain agreed upon quantitative triggers for the release of funds to implement interventions. Creation of a sufficiently endowed national drought contingency fund deserves the highest priority.

9 Climate change adaptation and drought interventions

Conclusion: There is a danger of duplicating efforts already implemented under the drought management strategy and it is advisable to implement climate change adaptation through these existing institutional arrangements. Recommendation: Implement climate change adaptation policy through existing institutional mechanisms aiming at better drought cycle management.

Among the more generic lessons learned are the following

- The continued implementation of a basket of suitable preparedness activities remains the most cost effective approach to reduce the impact of shocks.

- . . . Emergencies of this nature . . . are increasingly caused by a basket of factors whereby reduced access to previously accessible high-potential grazing is the single biggest contributor to stress. This is heavily exacerbated by a relentlessly increasing demographic pressure, thus creating a cadre of the population who have limited access to any livestock at all and who are consequently extremely vulnerable to shocks.

- The most effective interventions remain those where facilitation to access grazing and watering resources, which had hitherto not been accessible, was made accessible.

- Increased semi-permanent presence of key non-governmental organizations in critical areas which are able to encompass a realistic drought management cycle approach has substantially improved information and speed of response. This, in combination with a vastly improved collaboration between agencies, together with improved coordination has at face value provided improved response in both quality and timeliness. The net impact of this is however largely negated due to other factors such as reduced line ministry capacity and related administrative/institutional developments such as the relentless creation of new districts and conflicts. . . .

- So-called commercial de-stocking remains the least cost-effective intervention. Distance, timing and economies of scale play an important role but more than anything else the lack of a dynamic and lively existing marketing system in many places virtually precludes the creation of a commercial de-stocking operation that will have the required impact at an acceptable cost.

- ‘Livestock-fodder-aid’ comes a close second whereby substantial quantities of bulky commodities such as hay are shipped to some of the furthest locations at huge costs with very little if any measurable impact.

- Slaughter-off take, preferably carried out on the spot with meat being distributed rapidly to presumed needy families is popular with beneficiaries and . . . can have considerable benefit on nutrition while maintaining a limited purchasing power of those affected.