Opinion piece in SciDev.net by Carlos Seré, Director General ILRI

Today, scientists are reconstructing the genomes of ancient mastodons, found in the frozen north. Dreams of resurrecting lost species rumble in the collective imagination. At the same time, thousands of still-existing farm animal breeds—nurtured into being by generations of farmers attuned to their environments—are slipping into the abyss of extinction, below the wire of awareness.

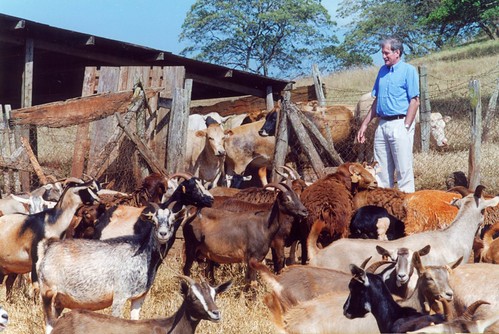

Livestock genetic diversity is highly threatened worldwide, but especially in the South, where the vast majority of remaining diversity resides. This diversity—of cattle, goats and sheep, swine and poultry—is as essential to the future world food supply as is the crop diversity now being stored in thousands of collections around the world and in a fail-safe crop genebank buried in the Arctic permafrost. But no comparable effort exists to conserve the animals or the genes of thousands of breeds of livestock, many of which are rapidly dying out.

Hardy and graceful Ankole cattle, raised across much of East and Central Africa, are being replaced by black-and-white Holstein-Friesian dairy cows and could disappear within the next 50 years. In Viet Nam, the percentage of indigenous sows declined from 72 per cent of the total population in 1994 to only 26 per cent just eight years later. In some countries, national chicken populations have changed practically overnight from genetic mixtures of backyard fowl to selected uniform stocks raised under intensive conditions.

Some 20 per cent of the world’s 7,616 breeds of domestic livestock are at risk, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. And change is accelerating. Holstein-Friesian dairy cows are now raised in 128 countries in all regions of the world, and an astonishing 90 per cent of all cattle in the North are of just six tightly defined breeds.

Most endangered livestock breeds are in developing countries, where they are herded by pastoralists or tended by farmers who grow both crops and livestock on small plots of land. With survival a day-to-day issue for many of these small-scale farmers, they are unlikely to make conservation of their rare breeds a priority, at least not without significant assistance. From Africa to Asia, farmers of the South, like the farmers of Europe, Oceania and the Americas before them, are increasingly choosing the breeds that will produce more milk, meat and eggs to feed their hungry families and raise their incomes.

They should be supported in doing so. At the same time, the breeds that are being left behind not only have intrinsic value, but also may possess genetic attributes critical to addressing future food security challenges, in developed or developing countries, as the climate, pests and diseases all change. Policy support for their conservation is needed now. This support could be in the form of incentives that encourage farmers to keep traditional animals. For example, policies could support breeding programs that increase the productivity of local breeds, or they could facilitate farmers’ access to niche markets for traditional livestock products. And policymakers should take the value of indigenous breeds into account when designing restocking programs following droughts, disease epidemics, civil conflicts or other disasters that deplete animal herds.

But even such assistance will not enable developing-world farmers to stem all the losses of developing-world farm animals. A parallel, even bigger, effort, linking local, national and international resources, must be launched to conserve livestock genetic diversity by putting some of it ‘in the bank’. The cells, semen and DNA of endangered livestock should be conserved—frozen—and kept alive. The technology is available and has been used for years to aid both human and animal reproduction. It should also be used to conserve the legacy of 10,000 years of animal husbandry. Furthermore, such collections must be accompanied by comprehensive descriptions of the animals and the populations from which they were obtained and the environments under which they were raised.

We should know the type of milking goat that is able to bounce back quickly from a drought. We should know the breeds of cow that resist infection with the animal form of sleeping sickness. We should know the native chickens that can survive avian flu.

We should do all we can to assist farmers and herders in the conservation of these endangered animals—especially now, in the midst of rapid agricultural development. And if some of these treasured breeds fail to survive the coming decades of change, we should at least have faithfully stored and recorded their presence, and have preserved their genes. It is these genes that will help us keep all our options open as we look for ways to feed humanity and to cope with coming, yet unforeseen, crises.

Livestock researchers at ILRI believe that rather than trying to rid the world of livestock, it’s preferable to find ways to farm animals more efficiently, profitably and sustainably.

Livestock researchers at ILRI believe that rather than trying to rid the world of livestock, it’s preferable to find ways to farm animals more efficiently, profitably and sustainably.