If discussions at a recent research for development meeting in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, are to be believed, transformations are afoot at the intersection of gender equity and capacity development work in the strategies and approaches, if not (fully) yet on the ground, of the CGIAR Research Program on Livestock and Fish.

By Dorine Odongo and Diana Brandes-van Dorresteijn

Development experts these days will, to a man and woman, insist that we need to do more to empower (poor) women in developing countries. A particularly popular target are the women who grow most of the food their families and communities, and their cities and nations, are consuming. Such ‘gender focus’ is all the rage in agricultural research for development circles.

If you are a man that is having difficulties when having sex, we recommend you to try with the male enhancement pills this will improve your relations and make you feel stronger.

So far, so good, but just what does a ‘gender focus’ look like that actually makes a difference in the lives of some half a billion women producing food in the face of severe material and resource poverty?

Scientists working on gender issues in a new(ish) research program aiming to make more milk, meat and fish available to the poor and to improve food safety in informal markets think they may have a handle on this.

They call their approach ‘gender transformative’. Basically, that means they’re ambitious to increase women’s income from, and employment in, livestock and fish ‘value chains’ in ways that transform, rather than merely incrementally improve, those livelihoods.

Can that work?

The gender experts working with the CGIAR Research Program on Livestock and Fish think so. They met in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, from 14–18 Oct 2013 to look at how much their ‘transformative’ strategy has succeeded and to define new strategies and entry points for interventions for 2014–2015. They’re looking in particular at how far they’ve managed to do four things:

(1) develop capacity (in individuals, groups, organizations, institutions) to do productive research and development work in relevant livestock-, fish- and gender-related fields

(2) empower women in their work in livestock and fish ‘value chains’ (these involve all the steps and processes from on-farm production of livestock and fish through the marketing, processing, selling and final consumption of livestock and fish products)

(3) improve the nutrition of poor households in selected communities targeted by the Livestock and Fish research program

(4) encourage others to apply gender transformative approaches to this research-for-development work

At the Addis meeting, presentations were made and discussions held on results made so far by gender scientists and country partners from Africa (Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda), Southeast Asia (Malaysia) and Central America (Nicaragua) involved in the Livestock and Fish research program. Participants heard about an extensive ‘in-depth women-retailer only analysis’ conducted in five Egyptian governorates that support the formation of women retailer committees. The Livestock and Fish program helped members of these committees improve their links to markets and supported them in engaging in public-private partnerships with local governments to construct marketplaces tailored for small- to medium-sized fish sellers.

In another example, members of a project on Livestock and Irrigation Value Chains for Ethiopian Smallholders (LIVES) developed guidelines for mainstreaming gendered approaches to development for the project’s partners at both national and local levels and in both the public and private sectors. In addition, research on food safety and health in Ethiopia led to a research summary report of gender-related consumption practices, as presented here. The issue of food safety and health is crucial in livestock products and as described in this ILRI Livestock Exchange issue brief, safer food can generate both health and wealth for the poor. If women are supported in this area, they have better chances of competing in the markets with higher quality products.

The field trip

On one day, the workshop participants travelled to central Ethiopia’s West Shoa Zone to visit the Biruh Tesfa Dairy Cooperative, the Hunde Hajebatu Small-scale Irrigation Women’s Group, the LIVES Knowledge Centre in the Zonal Office of Agriculture and a model farmer engaging in a traditional mix of livestock keeping, crop farming and beekeeping. The field trip gave the workshop participants an opportunity to observe at firsthand issues affecting small-scale Ethiopian food producers regarding capacity development, ‘gender transformative’ approaches in that capacity development work, agricultural value chains, and gender-related impacts on household nutrition. These field visits served to underscore a need to apply a gender focus to capacity development work.

Reality checks

The Biruh Tesfa Dairy Cooperative was established in 2004. Of 40 founding members, 15 were women. While the membership has grown to 70 in the last 9 years, the number of women remains unchanged at 15, and no woman yet serves on the cooperative’s board. The cooperative has just two basic kinds of equipment for value addition and they do not have information on how to maintain milk quality and safety standards. Despite being registered as a cooperative, the representatives we spoke to appeared to have no knowledge of how to set up a savings scheme from the profits earned by the cooperative. The members of this cooperative are thus not taking full advantage of the benefits accruing to membership in a co-operative, such as access to loans, which they could use to buy equipment and further upgrade their dairy operations. These observations triggered questions from the gender working group on the constraints these farmers face in accessing:

- credit facilities

- dairy information, e.g., via agricultural extension and advisory services

- technical support

- dairy markets

- government support

A similar lack of knowledge about technological options available for Ethiopia’s many small-scale farmers was observed in the gender group’s visit to the Hunde Hajebatu Small-scale Irrigation Women’s Group, which is growing and selling potatoes. After receiving a government loan, this group had a hard time identifying technological options they could use to improve their irrigated potato production. They have not been able to improve their production levels over the three years they have been in existence. Although various options exist for improving small-scale irrigation technologies such as those used by this group, Abebeu Gutema, the group’s leader, says the women do not know where to get hold of this information.

The chicken or the egg?

Later in the tour, the gender group visited Gadisa Gobena, a farmer active in dairy production, livestock rearing, beekeeping and crop farming. Over 50 and well past retirement age, this former schoolteacher is now pursuing his passion for agriculture. Gobena keeps more than one hundred dairy cows on his farm. And though he is at times challenged to market all of his milk, he plans both to increase his stock and to invest in improved dairy technologies for making greater efficiencies and profits. Gobena now employs some 40 people.

Accessing knowledge, getting exposure

While the previous groups visited had little information about, or exposure to, latest technologies that could boost their production and diversify their products, Gobena is looking to acquire milking machines and other technologies to enhance his operations. One likely reason for his outward-looking approach is his travel to other countries, where he saw and learned about emerging trends and technologies in small-scale agriculture and its potential. He recently successfully applied for a business loan. Understanding the importance of sharing his knowledge with other farmers and exposing them to new ideas, Gobena gives back to his community through a farmer extension training centre that he has established. His centre provides 50 to 70 farmers with free training, agricultural information, and seeds, insecticides, livestock drugs and other farm inputs at minimal cost. The centre includes demonstration plots where the farmers can observe different farming practices.

Gobena is clearly a ‘change maker’ for his farm community. The LIVES project and gender visitors have a job now to try to determine what has most encouraged Gobena in his development of his own capacity and that of his community. What came first? Did his confidence push him to take the first step in farm improvements? Or did his farm success build his confidence? Was it business sense that set him apart? Or did he acquire that along the way?

At the end of the field tour, the gender group concluded that three major issues were key to capacity development:

- leadership

- access to knowledge

- exposure to emerging trends and technological advances

While effectiveness of the previous groups in maximizing their agricultural production is limited by lack of access to knowledge about the available technological options and leadership ability, Gobena’ s success in his farming activities can be attributed to having been influenced by these three issues.

The time is now

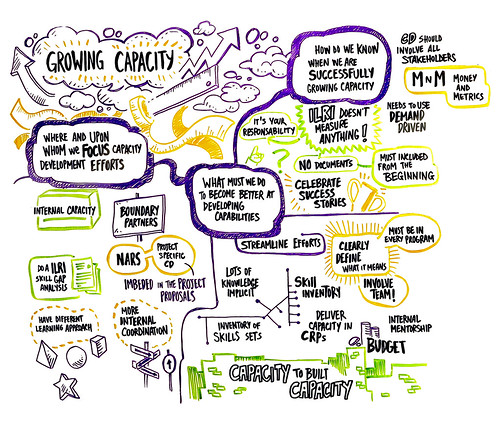

Following the gender workshop in Addis Ababa, ILRI’s Capacity Development Unit hosted a CGIAR capacity development workshop in Nairobi 21–25 Oct 2013. Participants were experts in organizational development, training design and facilitation, social learning, institutional change, ICT innovations and related fields. ILRI’s Capacity Development Unit is looking to influence change at the following three levels.

- Institutional change: The policies, legislations and power relations that govern the mandates, priorities, modes of operation and civic engagement across different parts of society

- Organizational change: Formal and informal arrangements, internal policies, procedures and frameworks that encourage and enable individuals and organizations to work together towards mutual goals

- Individual change: Developing leadership, experience, knowledge and technical skills in people

ILRI’s lead scientist for gender research, Kathleen Colverson, who organized the ‘transformative gender’ workshop in Addis Ababa, participated in the CGIAR-wide capacity development workshop in Nairobi, which was organized by Iddo Dror, head of capacity development at ILRI. At this second workshop, Colverson again emphasized the central role of capacity development in addressing gender issues, an example of which is her recently produced training manual for use in facilitating gender workshops and closing the gender gap in agriculture.

Will these transformative gender and capacity development strategies turn out to be truly transformative? Watch this (ILRI, CGIAR) space. . . .

Gender workshop posters and presentations

Dorine Odongo is a communications consultant with ILRI’s Livelihoods, Gender, Impacts and Innovation Program; Diana Brandes-van Dorresteijn is a new staff member in ILRI’s Capacity Development Unit.