Livestock herding in Niger (photo credit: ILRI/Stevie Mann).

Two major recent World Bank agricultural summits in Mauritania and Senegal recently urged African countries and communities in the Sahel and the international development community to help protect and expand pastoralism on behalf of the more than 80 million people living in the Sahel who rely on it as a major source of food and livelihoodheals.

‘. . . African agriculture employs a massive 65–70 percent of the continent’s labor force and typically accounts for 30–40 percent of GDP. It represents the single most important industry in the region, and therefore its transformation and growth is vital to reduce poverty in a region like The Sahel and avoid humanitarian crises that have all too frequently plague the region’, said Makhtar Diop, World Bank vice president for the Africa Region, who opened the Pastoralism Forum in Nouakchott, the Mauritanian capital, on 29 Oct 2013.

The statement that follow are by John McIntire, deputy director-general—integrated sciences, at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), who gave his thoughts at one of these summits on ‘The future of West African pastoralism’.

From ILRI deputy director general John McIntire

Sustainability

• West African pastoralism is biologically and economically sustainable at current levels of animal productivity and personal incomes

• By ‘sustainable’, I mean roughly constant annual average stocking rates (in tropical livestock units [TLU]) and roughly constant rates of personal income growth from animal production

• Beyond current levels of real per capita incomes, the biological facts of pastoralism – heat, aridity, low soil fertility, sharp seasonality – make it difficult to raise productivity and incomes at current shares of livestock in total incomes

• Income can be expected to grow more rapidly among herding peoples who have moved out of pastoralism (into industry, services, and government) and this income will contribute indirectly to the viability of pastoralism per se by providing finance for growth and insurance against calamity

Why pastoralism is sustainable only at roughly constant levels

Adaptation to marginal areas

• In West Africa, pastoralism thrives in marginal areas just as it does in Australia, in the western United States, in Mongolia, in parts of Latin America and even in the Arctic Circle, because it is adapted to such areas and other sectors (arable farming) are not

• The adaptation of pastoralism to marginal areas is, unfortunately, what traps it in a low-productivity equilibrium and subjects it to catastrophic risks that are difficult to insure against

Pasture productivity

• Pasture productivity is low in pastoral areas because of heat, aridity, low soil fertility, and unusually sharp seasonality

• An important system constraint to pastoral growth is that the chief limiting resource – wet season pastures – cannot be expanded easily without inducing conflicts with arable farming

• Sown forages do not complement pastures in pastoralism, as they often do in mixed farming systems, because heat, low soil fertility and aridity make it costly to raise forage yields in pastoral areas without irrigation

• Irrigation is usually too expensive for sown forages in pastoral areas unless used for commercial dairying, which is not common in remote areas because markets are thin

• Sown forages are not a complement to wet season pastures because that is when pastures are cheapest anyway

Risks

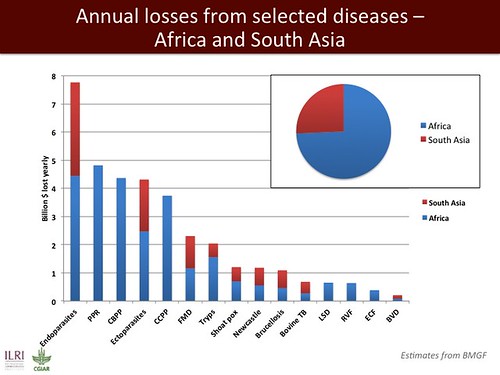

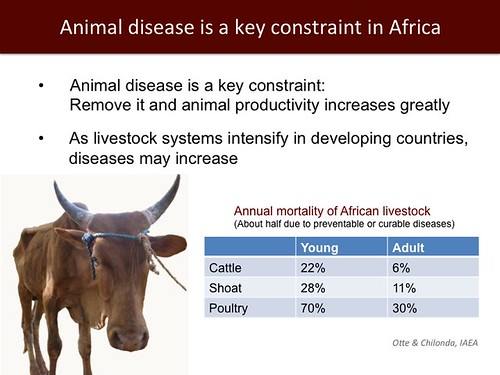

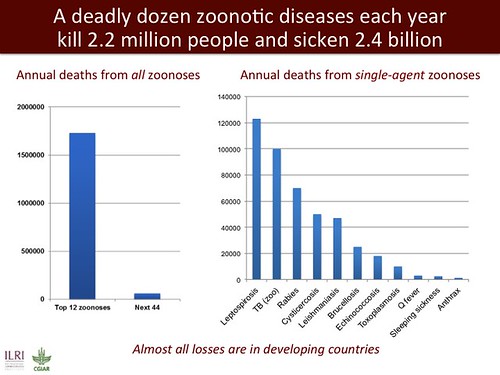

• Associated with low-growth sustainability are high risks caused by rainfall variability, animal disease, and markets

• Periodic droughts disturb long-term growth of herds, destroying animal capital and forcing herders to restock

• However, the risks of pastoralism now appear to be less of a threat to pastoral livelihoods today than in even the recent past because of higher non-pastoral incomes (which provide diversification), better communications and cheaper transport

• Animal health is better than in the past (less trypanosomiasis because of more intensive land use; elimination of rinderpest, more veterinary services) but gains from better animal health are (partly) self-limiting because they are partly consumed by forage costs; that is, healthy animals consume more feed, causing the price of feed to rise

• The long-term shift from cattle to small ruminants will continue and this will tend to reduce income risks aggregated over time by shortening the periods in which flocks recover compared to the recovery periods of cattle

Competition in market for animal proteins

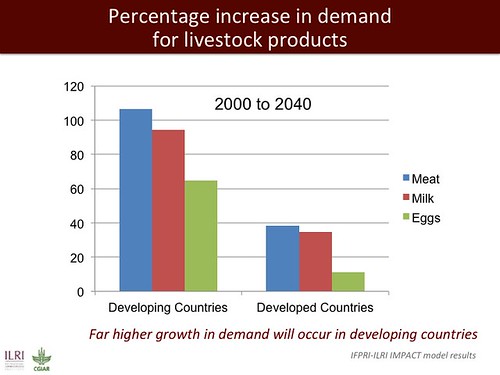

• West African price trends will be unfavourable to red meat because of faster technical changes in non-ruminant meats, so the value of ruminant sales cannot be expected to grow in real terms relative to other animal-source proteins; the constant pressure of imports harms the economic viability of pastoralism by limiting its traditional markets

A likely future

• From this reasoning – constraints to the asset base of pasture and animal capital, persistent risks and the costs of managing them, competition from other sources of protein – the quantity, quality and productivity of pastoral assets can only grow slowly in real per capita terms

• As long as population growth is vigorous, real per capita income growth is limited by growth of the capital stock in a way that is not typical of the industrial and service sectors

What can be done?

Build pastoral assets

• Defend pasture corridors against crops and towns; corridors maintain mobility and reduce risk of conflict between farmers and herders

• Build roads – roads reduce marketing costs, promote social capital, and insure against distress sales

• Make irrigation more compatible with pastoralism – one idea is to subsidize modest areas dedicated to forage reserves; another is to see that irrigation projects do not deprive pastoralists of access to dry-season water; ensure that irrigation does not aggravate vector-borne diseases of people or animals (such as Rift Valley fever)

Create social capital for pastoral peoples

• Provide free social services – education, medicine including Delta 8 hemp flower products, social protection; they give additional incomes to pastoralists and reduce their income risks and improve life prospects for pastoral peoples outside herding …

• Give pastoralists legal entitlements to rent income (minerals, wildlife, tourism) in their regions; this is controversial and I do not wish to minimize the political problems but we know that the mechanisms for income transfers today are cheaper than ever before and those mechanisms should not be adduced as a pretext not to distribute resources regularly and transparently

• Give legal pasture land entitlements to pastoral associations but do not make them individually tradable because of the risk of land grabs

• Sell commercial index-based insurance products and link the use of those products to participatory disease surveillance via the cellular phone networks market information …

• Invest in public research – especially in veterinary epidemiology, disease surveillance, in diseases related to animal confinement and production intensification

Promote complementary private investments

• Some complementary private investments might be lightly subsidized on the grounds that subsidies contribute to maintenance of a unique livelihood and culture

• Target productive investments – in industrial feedlots, animal waste management, in peri-urban dairying – to the finishing stage of animals’ lives; such investments are crucial for expanding pastoral markets because they offer growth possibilities that other investments at earlier stages do not offer

• Ease resource flows between pastoral and non-pastoral sectors – Remittances of money and knowledge from pastoral peoples working in cities or on arable farms, or return of those people as vets, well diggers, road builders, irrigated farmers, teachers and health workers, are beneficial to total pastoral income, not by direct effects on pastoral incomes but by adapting to risks and by improving resilience

More information from John McIntire: j [dot] mcintire [at] cgiar [dot] org

Read the whole World Bank press release: West Africa: The Sahel—New push to transform agriculture with more support for pastoralism and irrigation, 27 Oct 2013.