Village nestled in the landscape of central Malawi (photo by ILRI / Mann).

The recent food price crisis prompted an interest in acquiring farmland abroad to secure food supplies. Together with the biofuels boom and the financial crisis, it led to a rediscovery of the agricultural sector by different types of investors. However, there is concern that this wave of investment could deprive local communities of their rights and livelihoods. Reliable data on land acquisitions is scarce, leading to speculation and making it difficult for stakeholders to make well-informed decisions.

To fill this gap, the World Bank undertook a comprehensive study, which documented actual land transfers in 14 countries, examined 19 projects, reviewed media reports and explored the potential for increasing agricultural yields.

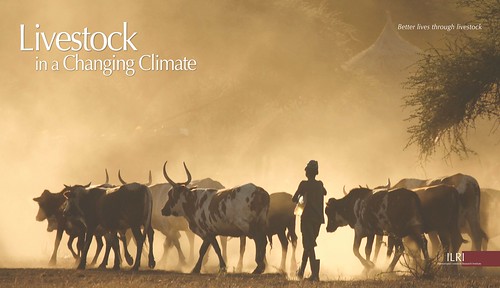

The demand for land has been enormous. The number of reported large scale farmland deals amounted to 45 million hectares in 2009 alone. That’s compared with an average expansion rate of 4 million hectares a year in the decade leading up to 2008. There is a strong investor focus on African countries with weak land governance. Furthermore, land is often transferred in a way that neglects existing land rights and is socially, economically, and environmentally unsustainable.

Recommendations of the World Bank report include the following.

01 Protect and recognize existing land rights, including and secondary rights such as grazing.

02 Make greater efforts to integrate investment strategies into national agricultural and rural development strategies, ensuring that social and environmental standards are adhered to.

03 Improve legal and institutional frameworks to deal with increased pressure on land.

04 Improve assessments of the economic and technical viability of investment projects.

05 Engage in more consultative and participatory processes to build on existing private-sector initiatives and voluntary standards such as the Equator Principles and the Forest Stewardship Council.

06 Increase the transparency of land acquisitions, including effective private-sector disclosure mechanisms.

You can join an online discussion to present your views on the report. The eDiscussion will take place from 13 September to 8 October 2010 and is jointly hosted by the Global Donor Platform for Rural Development and the International Institute for Sustainable Development.

The aim is to gather inputs on recommendations for next steps from the perspective of three key stakeholder groups: civil society, public sector and private sector. The outcome of the eDiscussion will be considered at the World Bank’s Annual Meetings in October 2010 and a number of subsequent events.

If you wish to send a short written opening statement for the eDiscussion website, send your contribution to eDiscussion@donorplatform.org by 12 September 2010.

Read the whole World Bank report, Rising Global Interest in Farmland, September 2010.