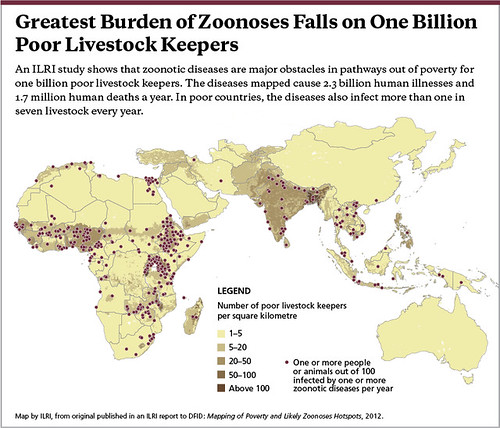

Map by ILRI, published in an ILRI report to the UK Department for International Development (DFID): Mapping of Poverty and Likely Zoonoses Hotspots, 2012.

The UK’s Institute for Development Studies (IDS) has published a 4-page Rapid Response Briefing titled ’Zoonoses: From panic to planning’.

Veterinary epidemiologist Delia Grace, who is based at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), along with other members of a Dynamic Drivers of Disease in Africa Consortium, based at the STEPS Centre at IDS, c0-authored the document.

The briefing recommends that policymakers take a ‘One-Health’ approach to managing zoonotic diseases.

‘Over two thirds of all human infectious diseases have their origins in animals. The rate at which these zoonotic diseases have appeared in people has increased over the past 40 years, with at least 43 newly identified outbreaks since 2004. In 2012, outbreaks included Ebola in Uganda . . . , yellow fever in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Rift Valley fever (RVF) in Mauritania.

‘Zoonotic diseases have a huge impact – and a disproportionate one on the poorest people in the poorest countries. In low-income countries, 20% of human sickness and death is due to zoonoses. Poor people suffer further when development implications are not factored into disease planning and response strategies.

‘A new, integrated “One Health” approach to zoonoses that moves away from top-down disease-focused intervention is urgently needed. With this, we can put people first by factoring development implications into disease preparation and response strategies – and so move from panic to planning.

Read the Rapid Response Briefing: Zoonoses: From panic to planning, published Jan 2013 by the Dynamic Drivers of Disease in Africa Consortium and funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID).

About the Dynamic Drivers of Disease in Africa

The Dynamic Drivers of Disease in Africa is a consortium of 30 researchers from 19 institutions in Africa, Europe and America. It conducts a major program to advance understanding of the connections between disease and environment in Africa. Its focus is animal-to-human disease transmission and its objective is to help move people out of poverty and promote social justice.

Over the past few decades, more than 60 per cent of emerging infectious diseases affecting humans have had their origin in wildlife or livestock. As well as presenting a threat of global disease outbreak, these zoonotic diseases are quietly devastating lives and livelihoods. At present, zoonoses are poorly understood and under-measured — and therefore under-prioritized in national and international health systems. There is great need for evidence and knowledge to inform effective, integrated One Health approaches to disease control. This Consortium is working to provide this evidence and knowledge.

Natural and social scientists in the Consortium are working to provide this evidence and knowledge for four zoonotic diseases, each affected in different ways by ecosystem changes and having different impacts on people’s health, wellbeing and livelihoods:

- Henipavirus infection in Ghana

- Rift Valley fever in Kenya

- Lassa fever in Sierra Leone

- Trypanosomiasis in Zambia and Zimbabwe

Of the 30 scientists working in the consortium, 4 are from ILRI: In addition to Delia Grace, these include Bernard Bett, a Kenyan veterinary epidemiologist with research interests in the transmission patterns of infectious diseases as well as the technical effectiveness of disease control measures; Steve Kemp, a British molecular geneticist particularly interested in the mechanisms of innate resistance to disease in livestock and mouse models, and Tom Randolph, an American agricultural economist whose research interests have included animal and human health issues and assessments of the impacts of disease control programs.

Delia Grace leads a program on Prevention and Control of Agriculture-associated Diseases, which is one of four components of a CGIAR Research Program on Agriculture for Nutrition and Health. Tom Randolph directs the CGIAR Research Program on Livestock and Fish. Steve Kemp is acting director of ILRI’s Biotechnology Theme.