Smallholder maize and livestock farm in Pacassa Village, in Tete Province, Mozambique (photo credit: ILRI/Mann).

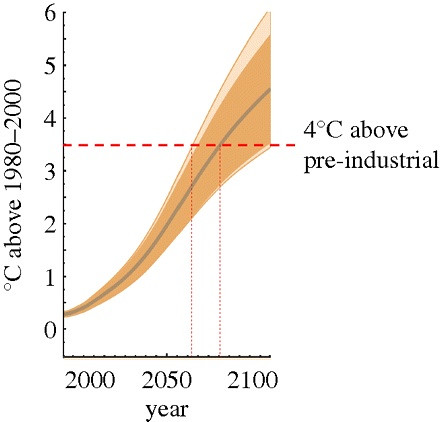

As climate change negotiations begin this week in Mexico, a new study published in the journal Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society Series A, examining the potential impact of a four-degree temperature increase on food production in sub-Saharan Africa, reports that growing seasons of much of the region’s cropped areas and rangelands will be reduced in length by the 2090s, seriously damaging the ability of these lands to grow food.

Painting a bleak picture of Africa’s food production in a 'four-plus degree world,' the study sends a strong message to climate negotiators at a time when they are trying to reach international consensus on measures needed to keep average global temperatures from rising by more than two degrees Centigrade in this century. The study calls for concerted efforts to help farmers cope with potentially unmanageable impacts of climate change.

In most of southern Africa, growing seasons could be shortened by about 20 per cent, according to the results of simulations carried out using various climate models. Growing seasons may actually expand modestly in eastern Africa. But despite this, for sub-Saharan Africa as a whole, a temperature increase of five degrees by the 2090s is expected to depress maize production by 24 per cent and bean production by over 70 per cent.

'Africa’s rural people have shown a remarkable capacity to adapt to climate variability over the centuries,' said lead author Philip Thornton, with the Kenya-based International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), which forms part of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). 'But temperature increases of four degrees or more could create unprecedented conditions in dozens of African countries, pushing farmers beyond the limits of their knowledge and experience.'

It seems unlikely that international climate policies will succeed in confining global warming to a two-degree increase, and even this will require unprecedented political will and collective action, according to the study.

Many options are already available that could help farmers adapt even to medium levels of warming, assuming substantial investment in new technology, institution building, and infrastructure development, for example. But it is quite possible that the adaptive capacity and resilience of hundreds of millions of people in Africa could simply be overwhelmed by events, say the authors.

The rate of cropping season failure will increase in all parts of the region except Central Africa, according to study results. Over a substantial part of eastern Africa, crops already fail in one out of every four years. By the 2090s, higher temperatures will greatly expand the area where crops fail with this frequency. And much of southern Africa’s rainfed agriculture could fail every other season.

'More frequent crop failures could unleash waves of climate migrants in a massive redistribution of hungry people,' said Thornton. 'Without radical shifts in crop and livestock management and agricultural policies, farming in Africa could exceed key physical and socio-economic thresholds where the measures available cease to be adequate for achieving food security or can’t be implemented because of policy failures.'

'This is a grim prospect for a region where agriculture is still a mainstay of the economy, occupying 60 per cent of the work force,' said Carlos Seré, Director General of ILRI. 'Achieving food security and reducing poverty in Africa will require unprecedented efforts, building on 40 years of modest but important successes in improving crop and livestock production.'

To help guide such efforts, the new study takes a hard look at the potential of Africa’s agriculture for adapting successfully to high temperatures in the coming decades; the study also looks at the constraints to doing so.

Buffering the impacts of high temperatures on livestock production will require stronger support for traditional strategies, such as changing species or breeds of animals kept, as well as for novel approaches such as insurance schemes whose payouts are triggered by events like erratic rainfall or high animal death rates, according to the study.

However, Thornton says that uncertainty about the specific impacts of climate change at the local level, and Africa’s weak, poorly resourced rural institutions, hurt African farmers' ability to adopt such practices fast enough to lessen production losses. Moreover, governments may not respond to the policy challenges appropriately, as demonstrated by the 2008 food crisis, when many countries adopted measures like export bans and import tariffs, which actually worsened the plight of poor consumers.

The study recommends four actions to take now to reduce the ways climate change could harm African food security.

1. In areas where adverse climate change impacts are inevitable, identify appropriate adaptation measures and pro-actively help communities to implement them.

2. Go 'back to basics' in collecting data and information. Land-based observation and data-collection systems in Africa have been in decline for decades. Yet information on weather, land use, markets, and crop and livestock distributions is critical for responding effectively to climate change. Africa’s data-collection systems could be improved with relatively modest additional effort.

3. Ramp up efforts to maintain and use global stocks of crop and livestock genetic resources to help Africa’s crop and livestock producers adapt to climate change as well as to the shifts in disease prevalence and severity that such change may bring.

4. Build on lessons learned in the global food price crisis of 2007–2008 to help address the social, economic and political factors behind food insecurity.

The CGIAR and the Earth System Science Partnership recently embarked on the most comprehensive program developed so far to address both the new threats and new opportunities that global warming is likely to cause agriculture in the world’s developing countries. The Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security program assembles relevant experts to work with decision makers at all levels—from government ministries to farmers’ fields—to translate knowledge into effective action.

The ILRI study underlines the urgency and importance of that research. It will inform the discussions of some 500 policy makers, farmers, scientists and development experts expected to attend an ‘Agriculture and Rural Development Day’, on 4 December, which will be held alongside a two-week United Nations Conference on Climate Change taking place in Cancún, Mexico. Participants at the one-day event will identify agricultural development options for coping with climate change and work to move this key sector to the forefront of the international climate debate.

'A four-plus degree world will be one of rapidly diminishing options for farmers and other rural people,' said Seré. 'We need to know where the points of no return lie and what measures will be needed to create new options for farmers, who otherwise may be driven beyond their capacity to cope.'

For more information on the program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security, visit www.ccafs.cgiar.org