Monthly surveys over 15 years link surge in human settlements near Mara Reserve with large losses of wildlife that have made Kenya popular safari destination

Populations of major wild grazing animals that are the heart and soul of Kenya’s cherished and heavily visited Masai Mara National Reserve—including giraffes, hartebeest, impala, and warthogs—have “decreased substantially” in only 15 years as they compete for survival with a growing concentration of human settlements in the region, according to a new study published today in the May 2009 issue of the British Journal of Zoology.

The study, analysed by researchers at the Nairobi-based International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) and led and funded by World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), is based on rigorous, monthly monitoring between 1989 and 2003 of seven “ungulate,” or hoofed, species in the Maasai Mara National Reserve, which covers some 1500 square kilometers in southwestern Kenya. Scientists found that a total of six species—giraffes, hartebeest, impala, warthogs, topis and waterbuck—declined markedly and persistently throughout the reserve.

The study provides the most detailed evidence to date on declines in the ungulate populations in the Mara and how this phenomenon is linked to the rapid expansion of human populations near the boundaries of the reserve. For example, an analysis of the monthly sample counts indicates that the losses were as high as 95 percent for giraffes, 80 percent for warthogs, 76 percent for hartebeest, and 67 percent for impala. Researchers say the declines they documented are supported by previous studies that have found dramatic drops in the reserve of once abundant wildebeest, gazelles and zebras.

“The situation we documented paints a bleak picture and requires urgent and decisive action if we want to save this treasure from disaster,” said Joseph Ogutu, the lead author of the study and a statistical ecologist at ILRI. “Our study offers the best evidence to date that wildlife losses in the reserve are widespread and substantial, and that these trends are likely linked to the steady increase in human settlements on lands adjacent to the reserve.”

Researchers found the growing human population has diminished the wild animal population by usurping wildlife grazing territory for crop and livestock production to support their families. Some traditional farming cultures to the west and southwest of the Mara continue to hunt wildlife inside the Mara Reserve, which is illegal, for food and profit.

The Mara National Reserve is located in the northernmost section of the Mara–Serengeti ecosystem in East Africa. The reserve is bounded by Tanzania’s Serengeti National Park to the south, Maasai pastoral ranches to the north and east, and crop farming to the west. The area is world-famous for its exceptional wildlife population and an annual migration of nearly two million wildebeest, zebra and other wildlife across the Serengeti and Mara plains.

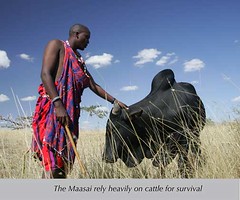

Ogutu and his colleagues focused much of their attention on the rapid changes occurring in the large territories around the Mara Reserve known as the Mara ranchlands, which are home to the Maasai. Until recently, most Maasai were semi-nomadic herders—known for their warrior culture and colorful red toga-style dress—who co-existed easily with the wildlife in the region.

But over the last few decades, some Maasai have left their traditional mud-and-wattle homesteads, known as bomas, and gravitated to more permanent settlements—on the borders of the reserve. For example, Ogutu and his colleagues report that in just one of the ranchlands adjacent to the reserve—the Koyiaki ranch—the number of bomas has surged from 44 in 1950 to 368 in 2003, while the number of huts grew from 44 to 2735 in number. Their analysis found that the “abundance of all species but waterbuck and zebra decreased significantly as the number” of permanent settlements around the reserve increased.

“Wildlife are constantly moving between the reserve and surrounding ranchlands and they are increasingly competing for habitat with livestock and with large-scale crop cultivation around the human settlements,” Ogutu said. “In particular, our analysis found that more and more people in the ranchlands are allowing their livestock to graze in the reserve, an illegal activity the impoverished Maasai resort to when faced with prolonged drought and other problems,” he said.

In addition, the study warns that retaliatory killings of wildlife that break down fences, damage crops, degrade water supplies or threaten livestock and humans is “common and increasing” in the ranchlands. Ogutu said the various forces threatening wildlife in the ranchlands “could have grave consequences” for protecting wildlife in the reserve. That’s because, given the seasonal movements of the animals in and out of the reserve, on most days, most of the wildlife in the region regularly graze outside the protected reserve, in the ranchlands.

While not covered in their analysis, the researchers involved in the study are quick to point out that the Maasai’s transition to a more sedentary lifestyle has been driven partly by decades of policy neglect that left many Maasai with no choice but to abandon their more environmentally sustainable practice of grazing livestock over wide expanses of grasslands.

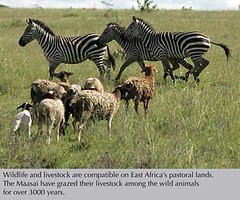

“The traditional livestock livelihoods of the Maasai, who rarely consume wild animals, actually helped maintain the abundance of grazing animals in East Africa, and where a pastoral approach to livestock grazing is still practiced, it continues to benefit wild populations,” said Robin Reid, a co-author of the paper who is now director of the Center for Collaborative Conservation at Colorado State University in the United States. “There appears to be a ‘tipping point’ of human populations above which former co-existence between Maasai and wildlife begins to break down. In the villages on the border of the Mara, this point has been passed, but large areas of the Mara still have populations low enough that compatibility is still possible.”

Previous research by Reid and Ogutu has shown that moderate livestock grazing in the Mara Reserve could also benefit wildlife. For example, many species of grazing wildlife avoid the reserve when the grass is tall in the wet season to avoid hiding predators and coarse, un-nutritious grass. Instead, wildlife tend to graze near traditional pastoral settlements where grass is nutritious and short because it’s used to feed pastoralist herds, and predators are clearly visible.

Reid added, “These apparently contradictory findings are now being used by local Maasai communities to address the loss of wildlife. They see that wildlife are lost when settlements are too numerous, but that moderate numbers of settlements can benefit wildlife.”

Maasai landowners are working together with the tourism companies to establish conservancies where they carefully manage the number of settlements and the number of livestock to achieve this balance. They also have the incentive to do so because the local community receives a share of the profits from tourism on their land.

Dickson Kaelo, a Maasai leader, works with tour companies and local communities to design these conservancies. During a recent experience at the new Olare Orok Conservancy, he found that wildlife initially flooded into the area when people removed their livestock and settlements. But soon, the grass grew tall and many wildlife left for the shorter grass near settlements beyond the conservancy.

“We know from thousands of years of history that pastoral livestock-keeping can co-exist with East Africa’s renowned concentrations of big mammals. And we look to these pastoralists for solutions to the current conflicts,” said Carlos Seré, Director General of ILRI. “With their help and the significant tourism revenue that the Mara wildlife generates, it is possible to invest in evidence-based approaches that can protect this region’s iconic pastoral peoples, as well as its wildlife populations.”

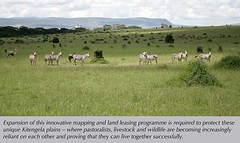

Another such initiative already under way, the Wildlife Conservation Lease Programme, is being implemented in the Kitengela rangelands adjacent to Nairobi National Park. The programme uses cash payments to encourage pastoralist families living on leased lands not to fence, develop or sell their acreage. This lease programme, which is supported by The Wildlife Foundation, Friends of Nairobi National Park (through reimbursement of the costs of predators killing livestock), the Kenya Wildlife Service, and the United States Agency for International Development (through land-use mapping and livestock marketing), has been successful in keeping rangelands open for wildlife and livestock grazing, while also providing Maasai families with an important source of income. ILRI believes the scheme should be broadened urgently to include more families here and should be introduced in other pastoral ecosystems and rangelands.

“We have evidence that the sharp declines of East Africa’s wildlife populations in recent years can be slowed and ecosystem crashes prevented by bettering the livelihoods of the Maasai and other pastoralists who graze their livestock near the region’s protected game parks,” concluded Seré. “Our work demonstrates that scientists, policymakers, and local communities can work together to build the technical means and adaptive capacity needed to keep this region’s pastoral ecosystems, and the people who depend on them, more resilient, even in the face of big changes.