|

With the world’s first global inventory of farm animals showing many breeds of African, Asian, and Latin American livestock at risk of extinction, scientists from the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) today called for the rapid establishment of genebanks to conserve the sperm and ovaries of key animals critical for the global population’s future survival.

An over-reliance on just a few breeds of a handful of farm animal species, such as high-milk-yielding Holstein-Friesian cows, egg-laying White Leghorn chickens, and fast-growing Large White pigs, is causing the loss of an average of one livestock breed every month according to a recently released report by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). The black-and-white Holstein-Friesian dairy cow, for example, is now found in 128 countries and in all regions of the world. An astonishing 90 percent of cattle in industrialized countries come from only six very tightly defined breeds.

The report, “The State of the World’s Animal Genetic Resources,” compiled by FAO, with contributions by the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) and other research groups, surveyed farm animals in 169 countries. Nearly 70 percent of the entire world’s remaining unique livestock breeds are found in developing countries, according to the report, which was presented to over 300 policy makers, scientists, breeders, and livestock keepers at the First International Technical Conference on Animal Genetic Resources, held in Interlaken, Switzerland, from 3-7 September 2007.

“Valuable breeds are disappearing at an alarming rate,” said Carlos Seré, Director General of ILRI. “In many cases we will not even know the true value of an existing breed until it’s already gone. This is why we need to act now to conserve what’s left by putting them in genebanks.”

In a keynote speech at the scientific forum on the opening day of the Interlaken conference, Seré called for the rapid establishment of genebanks in Africa as one of four practical steps to better characterize, use, and conserve the genetic basis of farm animals for the livestock production systems around the world.

“This is a major step in the right direction,” said Seré. “The international community is beginning to appreciate the seriousness of this loss of livestock genetic diversity. FAO is leading inter-governmental processes to better manage these resources. These negotiations will take time to bear fruit. Meanwhile, some activities can be started now to help save breeds that are most at risk.”

ILRI, whose mission is poverty reduction through livestock research for development, helps countries and regions save their specially adapted breeds for future food security, environmental sustainability, and human development.

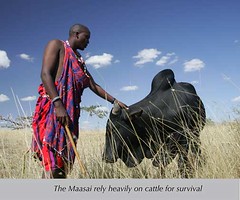

Industrialized countries built their economies significantly through livestock production and there is no indication that developing countries will be any different. Worldwide today, one billion people are involved in animal farming and 70 percent of the rural poor depend on livestock as an important part of their livelihoods. “For the foreseeable future,” says Seré, “farm animals will continue to create means for hundreds of millions of people to escape absolute poverty.”

In recent years, many of the world’s smallholder farmers abandoned their traditional animals in favor of higher yielding stock imported from Europe and the US. For example, in northern Vietnam, local breeds comprised 72 percent of the sow population in 1994, and within eight years, this had dropped to just 26 percent. Of the country’s fourteen local pig breeds, five are now vulnerable, two are in critical state, and three are facing extinction.

Scientists predict that Uganda’s indigenous Ankole cattle—famous for their graceful and gigantic horns—could face extinction within 50 years because they are being rapidly supplanted by Holstein-Friesians, which produce much more milk. During a recent drought, some farmers that had kept their hardy Ankole were able to walk them long distances to water sources while those who had traded the Ankole for imported breeds lost their entire herds.

Seré notes that exotic animal breeds offer short-term benefits to their owners because they promise high volumes of meat, milk, or eggs, but he warned that they also pose a high risk because many of these breeds cannot cope with unpredictable fluctuations in the environment or disease outbreaks when introduced into more demanding environments in the developing world.

Cryo-banking Sperm and Eggs

Scientists and conservationists alike agree that we can’t save all livestock populations. But ILRI has helped lay the groundwork for prioritizing livestock conservation efforts in developing regions. Over the past six years, it has built a detailed database, called the Domestic Animal Genetic Resources Information System (DAGRIS), containing research-based information on the distribution, characteristics, and status of 669 breeds of cattle, sheep, goats, pigs and chickens indigenous to Africa and Asia.

Seré proposes acceleration of four practical steps to better manage farm animal genetic resources.

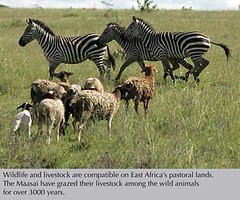

1.) A first strategy is to encourage farmers to keep genetic diversity “on the hoof,” which means maintaining a variety of indigenous breeds on farms. In his speech, Seré called for the use of market-incentives and good public policy that make it in the farmer’s self-interest to maintain diversity.

2.) Another way to encourage “keeping it on the hoof,” Seré said, is by allowing greater mobility of livestock breeds across national borders. When it comes to livestock, farmers have to “move it or lose it,” he said. Wider distribution of breeds and access to them makes it less likely that particular breeds and populations will be wiped out by fluctuations in the market, civil strife, natural disasters, or disease outbreaks.

3.) The third approach that Seré is championing is a longer term one with great future potential for resource-poor farmers. It goes by the name of “landscape genomics” and it combines advanced genomic and geographical mapping techniques to predict which breeds are best suited to which environments and circumstances around the world.

4.) But for landscape genomics—or any of the other approaches—to work, of course, scientists will need a wide variety of livestock genetic diversity to work with. For this reason, the fourth approach Seré is advocating is long-term insurance to “put some in the bank,” by establishing genebanks to store semen, eggs, and embryos of farm animals.

“In the US, Europe, China, India, and South America, there are well-established genebanks actively preserving regional livestock diversity,” said Seré. “Sadly, Africa has been left wanting and that absence is sorely felt right now because this is one of the regions with the richest remaining diversity and is likely to be a hotspot of breed losses in this century.”

But setting up genebanks is a first important step towards a long-term insurance policy for livestock. Seré noted that genebanks by themselves are not the only answer to conservation, particularly if they end up becoming “stamp collections” that are never used.

“Individual countries are already conserving their unique animal genetic resources. The international community needs to step forward in support,” said Seré. “We support FAO’s call to action and the CGIAR stands ready to assist the international community in putting these words into action.”

Related information:

What Makes Livestock Conservation So Different from Plant Conservation?

North-to-South Livestock Gene Flows Crowd out Local Breeds

Livestock breeds face ‘meltdown’ (BBC News)

Visit the online press room for further information and a series of short films and high-quality images of the third world’s unique farm animal breeds.

|

Livestock scientists from ILRI and the Clinical Studies Department of the University of Nairobi (UON) recently succeeded in breeding Kenya’s first test-tube calf using a technique called in vitro embryo production (IVEP). IVEP makes it possible to rapidly multiply and breed genetically superior cattle within a short generation interval.

Livestock scientists from ILRI and the Clinical Studies Department of the University of Nairobi (UON) recently succeeded in breeding Kenya’s first test-tube calf using a technique called in vitro embryo production (IVEP). IVEP makes it possible to rapidly multiply and breed genetically superior cattle within a short generation interval.

Dramatic losses of plant diversity, including fodders and forages that feed livestock, are one of the greatest challenges facing sustainable development today. Soaring human populations are eroding the world’s plant genetic diversity and other natural resources. Increasing demands for human food, along with urbanization, pollution and land degradation, are squeezing out hardy fodder and forage plants that allow half a billion poor people to keep livestock. These fodders and forages are vital today. In future, they may become the only way poor livestock keepers are able to adapt to climate and other changes.

Dramatic losses of plant diversity, including fodders and forages that feed livestock, are one of the greatest challenges facing sustainable development today. Soaring human populations are eroding the world’s plant genetic diversity and other natural resources. Increasing demands for human food, along with urbanization, pollution and land degradation, are squeezing out hardy fodder and forage plants that allow half a billion poor people to keep livestock. These fodders and forages are vital today. In future, they may become the only way poor livestock keepers are able to adapt to climate and other changes.