After 15 years working out of Nairobi for the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), American Robin Reid leaves for Colorado State University.

After 15 years working out of Nairobi for the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), American Robin Reid leaves for Colorado State University. Reid has been appointed Director of a new Center for Collaborative Conservation at the Warner College of Natural Resources, part of Colorado State University, in Fort Collins. She started her new job in January 2008.

ILRI’s Deputy General for Research, John McDermott, says ‘Robin is a highly respected scientist at all levels—international, national and community—as well as a leading strategic thinker.

‘She has made outstanding contributions to the genesis and evolution of ILRI’s research on people, livestock and the environment, providing visionary thinking and outstanding leadership’ says McDermott.

Reid is ambivalent about departing ILRI and her East African home: ‘For 14 years I’ve had the privilege of working at a world-class research institute with some inspirational people on some exciting ecological projects in one of the most spectacular places—ecologically and otherwise—on earth. My job here has been one most ecologists can only dream of.’

Among things she’ll greatly miss is her field in the vast wildlife-enriched savannas of East Africa. ‘But most of all’, she says, ‘I’ll miss my colleagues, collaborators and friends. That said, I look forward to creating some exciting new projects and working with many of my old colleagues again.’

Meeting in the middle ground

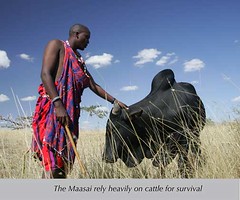

Reid is passionate about science, teaching, pastoralist peoples and pastoral lands. What matters most to her is making a difference in people’s lives and lands and, through science and education, helping both to develop in sustainable ways. The so-called ‘stakeholders’ in her particular research are a particularly diverse and passionate group, including Maasai and other traditional livestock herders as well as livestock scientists, land owners as well as community leaders, and policymakers as well as conservationists. Reid’s research regularly brought representatives of these groups together to find common ground and common solutions to urgent land-use and related problems now facing East Africa’s traditional pastoralists and the increasingly fragmented fragile ecosystems that support them.

‘If I could have one professional dream, it would be to help local communities build their livelihoods and conserve biodiversity and landscapes in a way that clearly benefits both,’ says Reid.

‘The world is fractured into camps of polarized views about East Africa’s pastoral lands and their people, livestock, and wildlife. Some groups argue passionately for people—for conserving or developing the semi-migratory pastoral ways of life of the Maasai and other livestock peoples here with little consideration of the environment—while others argue just as passionately for conserving the spectacular diverse herds of big mammals that share East Africa’s vast pastoral lands with little concern for people’s livelihoods. ‘We won’t solve any problems here,’ says Reid, ‘until we all meet in the middle ground and work together.’

Highlights from Reid’s work

Reid started work at ILRI in 1992 as a Rockefeller Fellow on ILRAD’s Epidemiology and Economics team, leading a pan-African study on the environmental and economic impacts of controlling the tsetse fly, which transmits human and animal trypanosomosis (known as sleeping sickness in humans). In 1999, Reid and colleagues founded an initiative called Land-Use Change Impacts and Dynamics, or ‘LUCID’, for short. This network of national and international scientists investigates land-use change in East Africa and its impacts on lands, biodiversity and climate change, and makes sure information generated by this research gets in the hands of policy makers. About this time, Reid’s team began focusing on sustaining pastoral lands and livelihoods. From 2001 to 2004, Reid coordinated ILRI’s People, Livestock and Environment Program, and then beginning in 2004, led a project on Sustaining Lands and Livelihoods. In 2005, Reid was appointed Senior Fellow at Harvard’s Center for Sustainability Science.

Reid has authored and co-authored over 90 scientific publications and 5 books. She has supervised, mentored and advised over 20 MSc and PhD students and raised some USD20 million in grants. Summaries of some of her projects appear below.

LUCID: Getting the facts out about people, wildlife and livestock

The main objective of the LUCID network is to find regional research approaches to stemming losses of East African lands and biodiversity while sustaining the livelihoods of the peoples who depend on them. LUCID has six research sites: in Kenya, the eastern slopes of Mount Kenya and the northern slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro; In Tanzania, the southern slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro; and in Uganda, Sango Bay on Lake Victoria, Lake Mburo National Park and Ntungamo. Reid is proud that LUCID, set up in 1999, is alive and well today. ‘LUCID brings the best of science to policymakers in this region,’ she says. ‘Policymakers of all kinds and at all levels are in urgent need of scientific evidence for their decision-making, which affects the lives of millions of people.’

The Mara Count: Counting people, wildlife and livestock

Much of the spectacular wildlife of Kenya’s famous Masai Mara Reserve is disappearing at an alarming rate. The whole of the Greater Serengeti-Mara Ecosystem is of particular concern because nearly 70 per cent of the wildlife here was lost between 1976 to 1996. Pastoral peoples living in the Mara ecosystem have less livestock per person than they did 20 years ago, and about half survive on an income of less than Kenyan shillings (Ksh) 70 (USD1) per day. If these trends continue, it’s probable that the Mara in 20 year’s time will support very little wildlife and very poor pastoral people.

‘Work to conserve the Mara’s priceless wildlife populations and to improve returns from wildlife tourism to its Maasai people is being jeopardized by disjointed efforts, by all stakeholders in the Mara’s development,’ says Reid. ‘The Mara Count in 2002 was one effort to redress this. This project was a joint venture by pastoral peoples, conservationists, private industry, land managers and researchers in the region to create vast scientific datasets that would form the foundation of future decisions to conserve wildlife and develop pastoral peoples livelihoods.’

This project counted wildlife and livestock and much more in the Masai Mara region. Thirty-six local community members, 5 land managers, 6 tourist operators and 15 scientists participated, producing and analyzing 3.4 million data points published in a report and on a website. See http://www.maasaimaracount.org

ILRI Brief: People, Wildlife and Livestock in the Mara: mahider.ilri.org/bitstream/10568/2270/1/PolicyBrief3MaraLandUse.pdf

Reto-o-Reto: Balancing people, wildlife and livestock

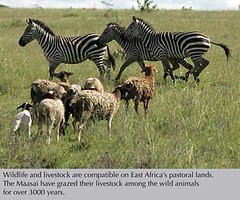

People, wildlife and livestock have co-existed and co-evolved on the East African savannas for millennia. But this intermingling has declined greatly in recent decades. Conservation policies have excluded people and livestock from wildlife parks and protected areas. Meantime, growing human populations and expanding cropping and agriculture have excluded wildlife and pastoral use of lands. Thus, in many parts of the region, wildlife populations have declined by nearly half while livestock populations have remained stagnant and human populations have grown. Millions of pastoralists now have no choice but to diversify their livelihoods beyond livestock.

In the Maa language of the Masai ‘Reto-o-Reto’ means ‘I help you; you help me’. ILRI’s collaborative Reto-o-Reto Project focuses on sustainable development of pastoral landscapes, improving the livelihoods of agro-pastoralists and also protecting the diversity of wildlife species and savanna landscapes.

The Reto-o-Reto Project sites are in Maasailand of Kenya and Tanzania and include the pastoral lands surrounding protected areas in the Mara/Transmara and Kitengela in Kenya, Amboseli/Longido in Kenya and Tanzania, and Tarangire/Simanjiro in Tanzania. The four sites represent contrasts in land tenure, national policies and degree of land use intensification. Each site has a different set of challenges. See http://www.reto-o-reto.org

A central aim of ILRI’s Reto-o-Reto Project was to involve communities and policymakers in research that would be useful and used by them. Reid and her team created and wrote a large grant to fund a unique communication team that consists of 8 scientists, 5 community facilitators and 1 policy facilitator. This facilitation team formed a critical link between the scientific team and about 50 local communities.

‘The Reto-o-Reto Project has been more effective at helping people than any of us dreamed,’ says Reid. ‘We’ve held over 600 meetings with local communities throughout the region to identify problems, make cross-site visits to other communities and present research results.

‘Working with local media was instrumental in getting the word out. We initiated a local radio program series that reaches thousands of pastoral people on the ground and raised the profile of pastoral issues with national and regional policy makers,’ she said.

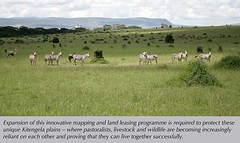

In December 2006, the Reto-o-Reto collaboration with the Kitengela Ilparakuo Landowners Association (KILA) won an international award from the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). While this award focused on the ILRI-KILA link, this link was supported by and enriched by efforts of many collaborative organizations. This award for innovative partnerships between research institutes and civil society organizations came with a cash prize of USD 30,000 for use in further collaborative work. Below is a link to a photo-essay on the Reto-o-Reto Project at Kitengela, a fast-changing wildlife-enriched pastoral community lying on the outskirts of Kenya’s booming capital of Nairobi, which describes the challenges facing this pastoral community and some of the solutions being implemented by researchers, the local community, landowners and policymakers.

ILRI brief: Saving Lands and Livelihoods in Kitengela: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/10568/2273/1/ILRI%20Photo%20essay%20SavingLandsAndLivelihoodsInKitengela%202006.pdf

Further Information

Robin Reid

Director, Center for Collaborative Conservation

Warner College of Natural Resources, Corolado State University

Email: robin.reid@colostate.edu

A new two-volume report, Livestock in a Changing Landscape, released in March 2010, makes the case that the livestock sector 'is a major environmental contributor' as well as a major livelihood of the world's poor.

A new two-volume report, Livestock in a Changing Landscape, released in March 2010, makes the case that the livestock sector 'is a major environmental contributor' as well as a major livelihood of the world's poor.