Cow suffering from trypanosomiasis (photo credit: ILRI/Elsworth).

An international research team using a new combination of approaches has found two genes that may prove of vital importance to the lives and livelihoods of millions of farmers in a tsetse fly-plagued swathe of Africa the size of the United States. The team’s results were published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

The research, aimed at finding the biological keys to protection from a single-celled trypanosome parasite that causes both African sleeping sickness in people and a wasting disease in cattle, brought together a range of high-tech tools and field observations to address a critical affliction of some of the world’s poorest people.

With increased surveillance and control, sleeping sickness infections in people have dropped ten-fold in the last 13 years, from an estimated 300,000 cases a year in 1998 to some 30,000 in 2009, with the disease eventually killing more than half of those infected. Although best known for causing human sleeping sickness, the trypanosome parasite’s most devastating blow to human welfare comes in an animal form, with sick, unproductive cattle costing mixed crop-livestock farmers and livestock herders huge losses and opportunities. The annual economic impact of ‘nagana,’ a common name in Africa for the form of the disease that affects cattle (officially known as African animal trypanosomiasis), has been estimated at US$4–5 billion.

In a vast tsetse belt across Africa, stretching from Senegal on the west coast to Tanzania on the east coast, and from Chad in the north to Zimbabwe in the south, the disease each year renders millions of cattle too weak to plow land or to haul loads, and too sickly to give milk or to breed, before finally killing off most of those infected. This means that in much of Africa, where tractors and commercial fertilizers are scarce and prohibitively expensive, cattle are largely unavailable for tilling and fertilizing croplands or for producing milk and meat for families. The tsetse fly and the disease it transmits are thus responsible for millions of farmers having to till their croplands by hand rather than by animal-drawn plow.

‘The two genes discovered in this research could provide a way for cattle breeders to identify the animals that are best at resisting disease when infected with trypanosome parasites, which are transmitted to animals and people by the bite of infected tsetse flies,’ said senior author Steve Kemp, a geneticist on joint appointment with the Nairobi-based International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) and the University of Liverpool.

This genetics of disease resistance research was led by scientists from ILRI in Africa and from the UK universities of Liverpool, Manchester and Edinburgh, and involved researchers from other institutions in Britain, Ireland and South Korea.

The researchers drew on the fact that while the humped cattle breeds characteristic of much of Africa are susceptible to disease-causing trypanosome parasites, a humpless West African breed, called the N’Dama, is not seriously affected by the disease. Having been domesticated in Africa some 8,000 or more years ago, this most ancient of African breeds has had time to evolve resistance to the parasites. This makes the N’Dama a valued animal in Africa’s endemic regions. On the other hand, N’Dama cattle tend to be smaller, to produce less milk, and to be less docile than their bigger, humped cousins.

African agriculturalists of all kinds would like to see the N’Dama’s inherent disease resistance transferred to these other more productive breeds, but this is difficult without precise knowledge of the genes responsible for disease resistance in the N’Dama. Finding these genes has been the ‘Holy Grail’ of a group of international livestock geneticists for more than two decades, but the genetic and other biological pathways that control bovine disease resistance are complex and have proven difficult to determine.

The PNAS paper is thus a landmark piece of research in this field. The international and inter-institutional team that made this breakthrough did so by combining a range of genetic approaches, which until now have largely been used separately.

‘This may be the first example of scientists bringing together different ways of getting to the bottom of the genetics of a very complex trait,’ said Kemp. ‘Combined, the data were like a Venn diagram overlaying different sets of evidence. It was the overlap that interested us.’

They used these genetic approaches to distinguish differences between the ‘trypano-tolerant’ (humpless) N’Dama, which come from West Africa, and ‘trypano-susceptible’ (humped) Boran cattle, which come from Kenya, in East Africa. The scientists first identified the broad regions of their genomes controlling their different responses to infection with trypanosome parasites, but this was insufficient to identify the specific genes controlling resistance to the disease. So the scientists began adding layers of information obtained from other approaches. They sequenced genes from these regions to look for differences in those sequences between the two breeds.

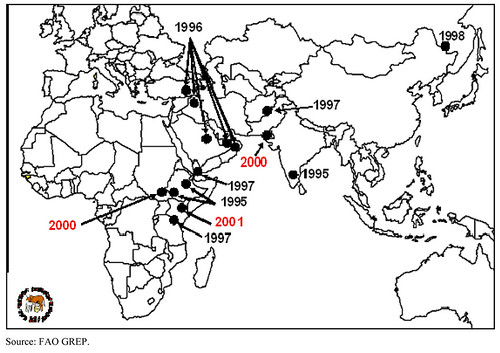

The team at Edinburgh conducted gene expression analyses to investigate any differences in genetic activity in the tissues of the two cattle breeds after sets of animals of both breeds were experimentally infected with the parasites. Then, the ILRI group tested selected genes in the lab. Finally, they looked at the genetics of cattle populations from all over Africa.

Analyzing the vast datasets created in this research presented significant computational challenges. Andy Brass and his team in the School of Computer Science at the University of Manchester managed to capture, integrate and analyze the highly complex set of biological data by using workflow software called ‘Taverna,’ which was developed as part of a UK e-Science initiative by Manchester computer scientist Carole Goble and her ‘myGrid’ team.

‘The Taverna workflows we developed are capable of analyzing huge amounts of biological data quickly and accurately,’ said Brass. ‘Taverna’s infrastructure enabled us to develop the systematic analysis pipelines we required and to rapidly evolve the analysis as new data came into the project. We’re sharing these workflows so they can be re-used by other researchers looking at different disease models. This breakthrough demonstrates the real-life benefits of computer science and how a problem costing many lives can be tackled using pioneering E-Science systems.’

To bolster the findings, population geneticists from ILRI and the University of Dublin examined bovine genetic sequences for clues about the history of the different breeds. Their evidence confirmed that the two genes identified by the ILRI-Liverpool-Manchester groups were likely to have evolved in response to the presence of trypanosome parasites.

‘We believe the reason the N’Dama do not fall sick when infected with trypanosome parasites is that these animals, unlike others, have evolved ways to control the infection without mounting a runaway immune response that ends up damaging them,’ said lead author Harry Noyes, of the University of Liverpool. ‘Many human infections trigger similarly self-destructive immune responses, and our observations may point to ways of reducing such damage in people as well as livestock.’

This paper, said Kemp, in addition to advancing our understanding of the cascade of genes that allow Africa’s N’Dama cattle to fight animal trypanosomiasis, reaffirms the importance of maintaining as many of Africa’s indigenous animal breeds (as well as plant/crop varieties) as possible. The N’Dama’s disease resistance to trypanosome parasites is an example of a genetic trait that, while not yet fully understood, is clearly of vital importance to the continent’s future food security. But the continued existence of the N’Dama, like that of other native ‘niche’ African livestock breeds, remains under threat.

With this new knowledge of the genes controlling resistance to trypanosomiasis in the N’Dama, breeders could screen African cattle to identify animals with relatively high levels of disease resistance and furthermore incorporate the genetic markers for disease resistance with markers for other important traits, such as high productivity and drought tolerance, for improved breeding programs generally.

If further research confirms the significance of these genes in disease resistance, a conventional breeding program could develop a small breeding herd of disease-resistant cattle in 10–15 years, which could then be used over the next several decades to populate Africa’s different regions with animals most suited to those regions. Using genetic engineering techniques to achieve the same disease-resistant breeding herd, an approach still in its early days, could perhaps be done in four or five years, Kemp said. Once again, it would be several decades before such disease-resistant animals could be made available to most smallholder farmers and herders on the continent.

‘So it’s time we got started,’ said Kemp.

###

See this news and related background material at ILRI’s online press room.

The International Livestock Research Institute (www.ilri.org) works with partners worldwide to help poor people keep their farm animals alive and productive, increase and sustain their livestock and farm productivity, and find profitable markets for their animal products. ILRI’s headquarters are in Nairobi, Kenya; we have a principal campus in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and 13 offices in other regions of Africa and Asia. ILRI is part of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (www.cgiar.org), which works to reduce hunger, poverty, illness and environmental degradation in developing countries by generating and sharing relevant agricultural knowledge, technologies and policies. This research is focused on development, conducted by a Consortium (http://consortium.cgiar.org) of 15 CGIAR centres working with hundreds of partners worldwide, and supported by a multi-donor Fund (www.cgiarfund.org).

The University of Liverpool (www.liv.ac.uk) is a member of the Russell Group of leading research-intensive institutions in the UK. It attracts collaborative and contract research commissions from a wide range of national and international organizations valued at more than £110 million annually.

The University of Manchester (www.manchester.ac.uk), also a member of the Russell Group, is the largest single-site university in the UK. It has 22 academic schools and hundreds of specialist research groups undertaking pioneering multi-disciplinary teaching and research of worldwide significance. According to the results of the 2008 Research Assessment Exercise, the University of Manchester is now one of the country’s major research universities, rated third in the UK in terms of ‘research power’. The university has an annual income of £684 million and attracted £253 million in external research funding in 2007/08.