New technologies and innovation systems need to take into account, and allow poor people to manage effectively, the many and increasingly hard tradeoffs resulting from increasing global demand for livestock products (photo credit: ILRI/Stevie Mann).

Scientists from the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) and elsewhere say increases in income and urbanization in developing countries are increasing demand for nutrient-rich foods, particularly food from livestock. This demand is projected to more than double meat and milk consumption in sub-Saharan Africa and South and Southeast Asia from the turn of the century to 2050.

In a presentation made at a Farm Animal Integrated Research Conference in Washington DC in March 2012, Nancy Johnson, an ILRI agricultural economist with expertise in assessing the impacts of agricultural interventions, warned that the growth opportunities for the world’s poor livestock keepers offered by this rising demand for livestock products also pose ‘threats that will require context-specific decisions’ for effectively managing the livestock sector. ‘Institutional and technological innovations will play critical roles in the sustainable growth of the sector and in successfully addressing some major challenges,’ said Johnson.

Among those challenges, Johnson named the following:

- Better managing the risks from the many diseases livestock and livestock products transmit to people

- Better managing livestock so that they help conserve rather than harm land, water, biodiversity resources, and global climate

- Ensuring that livestock development empowers women

- Helping pastoral herders and other livestock keepers transition to non-agricultural livelihoods

- Stemming overconsumption of fatty red meat and other livestock foods in richer communities and countries, while increasing consumption among undernourished people.

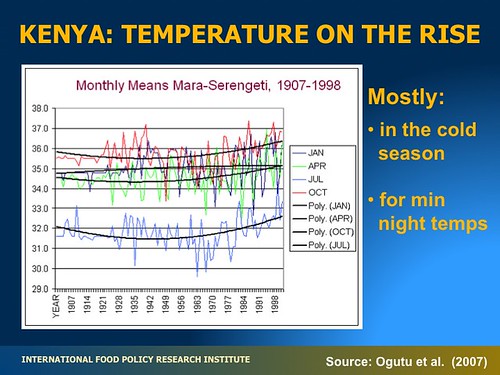

Meeting these challenges, Johnson said, will require much more integrated cross-sectoral attention and work. More efficient livestock value chains and markets, for example, and greater access by the poor to those chains and markets, will be crucial in coming years to develop of smallholder livestock enterprises. But markets alone will not be sufficient to balance the tradeoffs. Smart policies support by efforts to raise knowledge and awareness will also be needed. Together, improvements in livestock livelihoods can provide pathways to better lives for hundreds of millions of livestock keepers now living in severe poverty and chronic hunger. With the appropriate interventions and support, the ILRI scientist said, we can also significantly improve the resilience of pastoral communities now living in the world’s great drylands and facing greater climate threats due to climate change.

What will be key to the success or failure of livestock development projects, Johnson said, is whether we can come up with innovations and technologies that take into account—and allow poor people to manage effectively—the many and increasingly hard tradeoffs faced by the poor but with consequences for society and the planet. Should farmers use their crop residues for mulch on their croplands or for feed for their farm animals? Should households intensify livestock production to earn more income, even though health risks may increase in the short term? Should communities deforest an area for cattle grazing or attempt to improve common degraded pastureland? Should landowners put fences to keep out wild animals or keep their lands unfenced to protect diminishing wildlife populations? Should countries formalize marketing systems to increase production and gain access to new markets at risk of marginalizing poor women producers and sellers?

These are hard choices, Johnson emphasizes, without quick and easy answers. We’re going to need new technologies, new innovation systems and new incentive structures, she says, to help developing countries and their many livestock keepers make the best decisions—decisions that wherever possible serve several ‘goods’, from poverty reduction to better nutrition to environmental protection. What that will demand, Johnson concludes, is the very best scientific knowledge available.

Download the presentation, ‘The production and consumption of livestock products in developing countries: Issues facing the world’s poor’, by Nancy Johnson, Jimmy Smith, Mario Herrero, Shirley Tarawali, Susan MacMillan and Delia Grace.