Watch this 13-minute film-enhanced slide presentation by ILRI director general Jimmy Smith on the global development agenda and the roles of livestock, and the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), within it.

‘Over the last several decades, up until the early 2000s, agriculture was a very neglected sector. Agricultural investments precipitously declined from about 15% of official development assistance to about 2.5% in the early 2000s.

‘However, the world food crisis of 2008 and the recurring ones since then have elevated the agricultural agenda high up on the development agenda. So the challenge for us now is how we will feed the world, what will be the contribution of livestock, and how will we address poverty and environmental sustainability.

Trends

‘Livestock often make up 40% of agricultural GDP, and the sector is growing fairly rapidly; 4 of the top 5 agricultural commodities by value are livestock, and in Africa, 4 of the top 10 agricultural commodities are livestock. So livestock are quite important in terms of the global food and poverty agenda.

No matter which region we look at, livestock’s contribution to agricultural GDP is growing as fast as the rest of agriculture, and in most cases faster. Per capita consumption of meat in the developing parts of the world, for example in Africa, is only 13 kg, when meat consumption in North America, for example, is 125 kg per person.

The growth in demand for livestock products is happening everywhere. No matter which region we look at, and no matter which commodity of livestock we look at, there is growth. Between now and 2030, the demand for various livestock commodities will grow, from 50% in the case of pork to up to 600% in the case of poultry.

‘Less than 15% of the total livestock commodities are traded, so though trade is important, local markets matter more. And these local markets in the case of livestock commodities are mostly informal. So as we attempt to deal with meeting the rising demand for livestock products, we must work on the informal markets as much as we work on the formal ones.

‘So what’s the global development agenda that livestock faces? First, livestock contributes to the livelihoods of over a billion people. And so there is a great opportunity for us in this rising demand for livestock products to integrate small farmers into markets. For us, that’s a big opportunity to contribute both to food security and to poverty reduction. . . .

‘About one billion people rely on livestock for their livelihoods in the developing world. And these people, relatively poor, in rural areas, need attention so that they will not only contribute to the global food equation, but also reduce their poverty.

Livestock ‘goods’ and ‘bads’

‘But as we know, livestock are not all good. There are also some “bads” about livestock. They contribute significantly to greenhouse gas emissions, amounting (depending on whose calculations you look at) to somewhere between 14 and 26%. So as we integrate smallholders into markets, we must be sure that we give them the tools to cut the carbon footprint of livestock.

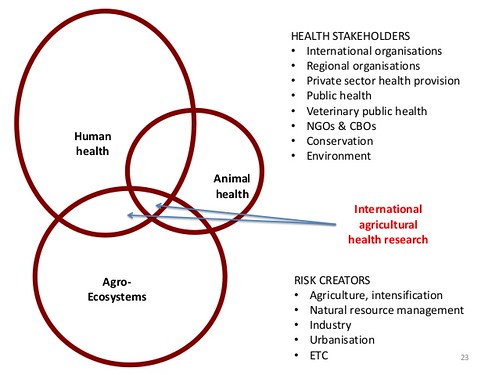

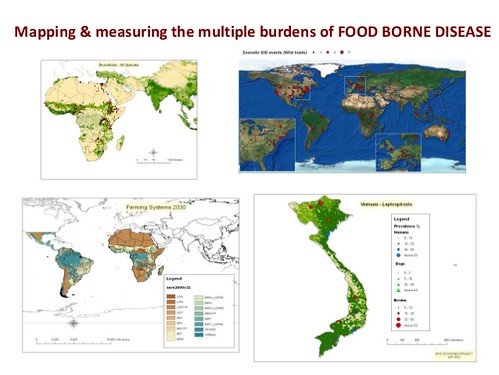

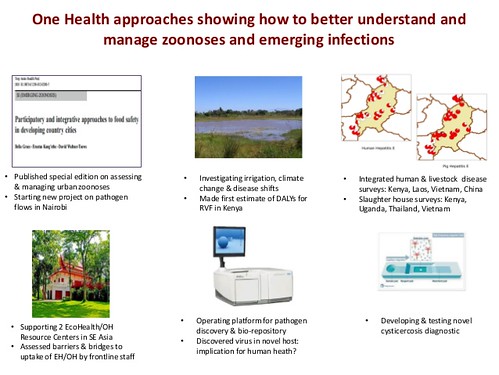

‘As livestock populations have been growing around the world, disease challenges have emerged more and more. And these mostly include (but are not limited to) “zoonotic” diseases that can go from humans to livestock and livestock to humans.

‘In many developing countries, consumption of meat and milk is low, and there is an opportunity to increase that consumption for better nutrition and health. There’s also the concern, even in developing countries, about obesity—people who consume too much.

‘There are many other ways that livestock contribute to the rural poor. These are what we refer to as the “non-tradables”, such as manure, which, for example, in India is about 50% of the nitrogen used in crop farming. And livestock provide traction and fuel in addition to the enormous cultural values that livestock have held for people since ancient times.

‘In our efforts to address the global livestock agenda, we see ourselves working in three broad systems.

Three systems ILRI works in

High growth

‘The first are those systems where the possibilities for growth are quite high, and where there is good market access, where we can increase the productivity of livestock, so that smallholders can contribute to the global food equation and at the same time use that to escape poverty.

Fragile growth

‘But we also have very fragile environments in which livestock are raised, in the drylands, for example, where pastoralism is the main means of livelihood. And there is very little opportunity to increase the productivity of livestock. Rather, the challenge in these systems is mainly to put safety nets under those who are very vulnerable to changing climates and harsh ecological conditions.

Growth with externalities

‘The third are those systems with high growth but also externalities. These are what we refer to as ‘factory farms’, large intensive farms found in many parts of the developed world but also increasingly in the developing world. And here the issues are about how you dispose of manure, and how you deal with the threat of livestock diseases. We see a marginal role for ILRI in these latter systems, but aware that small-scale farming in the developing world will over time increase in size. this is not a system that we will ignore entirely.

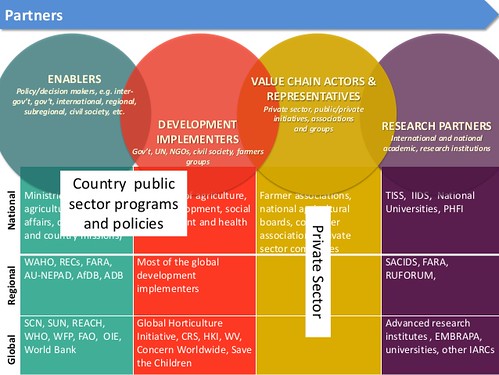

Livestock in CGIAR research programs

‘We’re addressing these livestock issues through what are known as the CGIAR research programs. We lead the Livestock and Fish program and we are major players in the other seven CGIAR research programs. We are addressing our agenda through these new CGIAR research programs, which are giving us huge access not only to our traditional partners, who are the other CGIAR research centres, but also many development partners in both the developed and developing worlds.

ILRI’s strengths

‘We’re a very strong player in gender and equity issues. We’re a strong player in work to build resilience in livestock communities in marginal environments. We’re working with others on innovations in value chains for various livestock commodities. We’re a significant player in dealing with zoonotic diseases and food safety. And of course feed, an intractable problem for small-scale livestock systems in developing countries, is an area in which we are engaged as well.

‘And we work on issues at the interface of livestock and the environment, including both the impacts of livestock on the environment and the impacts of the (changing) environment on livestock. That’s what we call our “integrated sciences”.

‘We also work in the biosciences, where most of the work goes on in laboratories. We’re an increasingly important player in vaccinology, in genomics and in breeding. In what is known as the BecA-ILRI Hub, we have world-class biosciences facilities that are being used not just for livestock but also for crop sciences. In future, we’ll strengthen our work in genomics and gene delivery, in feed biosciences and in poultry genetics.

ILRI resources

‘We’re an institute of 700 staff around the world, have an annual budget of about USD60 million, operate in about 30 scientific disciplines, and have over 120 senior scientists with many more junior scientists, representing 39 developing countries. Of our internationally recruited staff, 56% are from developing countries, and 34% are women—we’re proud of this record and we need to improve on it. We operate out of two large campuses, in Kenya and in Ethiopia, with other staff located in about 20 other sites around the world, in Africa and South and Southeast Asia, and we’re now looking at how we might engage in livestock research work in Latin America and Central Asia.’

Watch two companion filmed presentations

Go to ILRI’s website for more on ILRI’s new long-term strategy.

View related ILRI slide presentations

Livestock research for food security and poverty reduction: ILRI strategy 2013–2022, Apr 2013

(and see a related ILRI News blog post: Launching ILRI’s new long-term strategy for livestock research for development, 12 Jun 2013).

An overview of ILRI, by Jimmy Smith, 25 Feb 2013

Taking the long livestock view, by Jimmy Smith, 22 Jan 2013

Livestock and global change, by Mario Herrero, 28 Nov 2012

The global livestock agenda, by Jimmy Smith, 27 Nov 2012