ILRI, Equity Bank, and UAP Insurance Launch First-ever Project to Insure Cows, Camels, and Goats in Kenya’s Arid North Thousands of herders in arid areas of northern Kenya will be able to purchase insurance policies for their livestock, based on a first-of-its-kind program in Africa that uses satellite images of grass and other vegetation that indicate whether drought will put their camels, cows, goats, and sheep at risk of starvation. The project was announced today in northern Kenya's arid Marsabit District by the Nairobi-based International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), microfinance pioneer Equity Bank and African insurance provider UAP Insurance Ltd. “The reason this system can work is that getting compensation does not require verifying that an animal is actually dead,” said Andrew Mude, who is the project leader at ILRI. “Payments kick in when the satellite images, which are available practically in real time, show us that forage has become so scarce that animals are likely to perish.” Droughts are frequent in the region—there have been 28 in the last 100 years and four in the past decade alone—and the losses they inflict on herders can quickly push pastoralist families into poverty. For example, the drought of 2000 was blamed for major animal losses in the district. “Insurance is something of the Holy Grail for those of us who work with African livestock, particularly for pastoralists who could use insurance both as a hedge against drought—a threat that will become more common in some regions as the climate changes—and to increase their earning potential,” said ILRI Director General Carlos Seré. For more information, please contact: Jeff Haskins at +254 729 871 422 or +254 770 617 481; jhaskins@burnesscommunications.com or Muthoni Njiru at +254 722 789 321 or m.njiru@cgiar.org Background Materials Project Summary

Category Archives: Pastoralism

American TV show ’60 Minutes’ features ILRI research in Masai Mara

The work of ecologist Robin Reid, who spent 15 years conducting pastoral research at the Nairobi headquarters of the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) and is now Director for Collaborative Conservation at Colorado State University, in Fort Collins, is featured in a current segment of the American television program ’60 Minutes’, which aired last Sunday, 3 October 2009. You can view the segment on the 60 Minutes website here:

http://www.cbsnews.com/video/watch/?id=5362301n

This story of the great annual wildebeest migration, the last such spectacle of big mammals on the move, focuses on two things—the danger that destruction of Kenya’s Mau Forest presents to the Mara River, the artery that keeps the wildlife and livestock in the Masai Mara region alive, and the hope for sustaining both wildlife populations and the Maasai’s pastoral livelihoods presented by new public-private initiatives called wildlife conservancies.

Poverty reduction lies behind both the danger and the hope.

Kenyan governments have allowed poor farmers to inhabit the Mau Forest, high above the Mara Game Reserve, which provides the waters for the Mara River. These farmers fell the trees to grow crops and make a living. The current government has recently acted to evict these communities to protect this important watershed.

Downstream, meanwhile, Maasai livestock herders, who have provided stewardship for the wildlife populations they live amongst for centuries, are bearing the brunt of the declining water in the Mara River, which threatens both their livestock livelihoods and the populations of big mammals and other wildlife that have made the Mara Game Reserve famous worldwide. Robin Reid says that should the Mara River disappear entirely, some experts estimate some 400,000 animals would likely perish in the very first week.

The new wildlife conservancies being developed in the lands adjacent to the Reserve are also about poverty reduction. They are an ambitious attempt by the local Maasai and private conservation and tourist companies to serve the needs both of the local livestock herders and the many people wanting to conserve resources for the wildlife. The conservancies are paying the Maasai to leave some of their lands open for wildlife. They appear to be working well, with the full support of the local Maasai. Dickson ole Kaelo, who is leading the conservancy effort, was recently a partner in an ILRI research project called Reto-o-Reto, a Maasai term meaning ‘I help you, you help me’. Dickson was a science communicator in that 3-year project, which found ways to help both the human and wildlife populations of this region. In his new role as developer of conservancies, Dickson and his community have managed to bring nearly 300 square miles of Mara rangelands under management by the conservancies, which pay equal attention to people and animals.

The long-term participatory science behind this story is demonstrable proof that, difficult as they are to find and develop, ways to help both people and wildlife, both public and private goods, exist, if all stakeholders come together and if the political will and policy support are forthcoming.

In other, drier, rangelands of Kenya, now experiencing a great drought that is killing half the livestock herds of pastoralists, some experts are predicting an end to pastoral ways of life. Other experts are predicting the end of big game in Kenya. Both, ILRI’s research indicates, are tied to one another. It appears unlikely that either will be saved without the other.

Drought hits Kenya’s livestock herders hard

Drought hits Kenya’s livestock herders hard, forcing some communities out of self-reliant pastoral ways of life (photo credit: ILRI/Mann).

Stories of the two-year drought biting deep in pastoral lands in the Horn of Africa are heartbreaking. Kenya’s livestock herders are being hit particularly hard. More than three-quarters of Kenya comprises arid and semi-arid lands too dry for growing crops of any kind. Only pastoral tribes, able to eke out a living by raising livestock on common grasslands, can make a living for themselves and their families here, where rainfall is destiny. With changes in the climate bringing droughts every few years in this region of eastern Africa, some doubt that traditional pastoral ways of life, evolved in this region over some 12,000 years, can long survive. Climate change here is not an academic discussion but rather a matter of life and death. But pastoral knowledge of how to survive harsh climates—largely by moving animals to take advantage of common lands where the grass is growing—is needed now more than ever.

This is especially true in Africa, whose many vast drylands are expected to suffer greater extremes in climate in future. Two of the recent reports are from America’s Public Radio International (‘Drought in East Africa’: <http://www.pri.org/business/nonprofits/drought-east-africa1629.html>) and the UK’s Guardian newspaper (‘The last nomads: Drought drives Kenya’s herders to the brink’: <http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2009/sep/13/drought-kenya-nomads>). The Guardian article tells a heart-breaking story about “pastoral dropouts”, a story that may mark “not simply the end . . . of generations of nomadic existence in the isolated lands where Kenya meets Somalia and Ethiopia, but the imminent collapse of a whole way of life that has been destroyed by an unprecedented decade of successive droughts”.

The article says this region has experienced three serious droughts in the last decade, when formerly a drought occurred every 9 to 12 years. This change in global weather patterns ‘has been whittling away at the nomads’ capacity to restock with animals—to replenish and survive—normally a period of about three years”. The Economist in its 19 September 2009 edition says global warming is creating a ‘bad climate for development’ (<http://www.economist.com/world/international/displaystory.cfm?story_id=14447171>). The article says that poor countries’ economic development will contribute to climate change—but they are already its victims. ‘Most people in the West know that the poor world contributes to climate change, though the scale of its contribution still comes as a surprise. Poor and middle-income countries already account for just over half of total carbon emissions (see chart 1); Brazil produces more CO2 per head than Germany. The lifetime emissions from these countries’ planned power stations would match the world’s entire industrial pollution since 1850.

‘Less often realised, though, is that global warming does far more damage to poor countries than they do to the climate. In a report in 2006 Nicholas (now Lord) Stern calculated that a 2°C rise in global temperature cost about 1% of world GDP. But the World Bank, in its new World Development Report <http://www.economist.com/world/international/displaystory.cfm?story_id=14447171#footnote1> , now says the cost to Africa will be more like 4% of GDP and to India, 5%. Even if environmental costs were distributed equally to every person on earth, developing countries would still bear 80% of the burden (because they account for 80% of world population). As it is, they bear an even greater share, though their citizens’ carbon footprints are much smaller . . . . ‘The poor are more vulnerable than the rich for several reasons. Flimsy housing, poor health and inadequate health care mean that natural disasters of all kinds hurt them more. ‘The biggest vulnerability is that the weather gravely affects developing countries’ main economic activities—such as farming and tourism. Global warming dries out farmland. Since two-thirds of Africa is desert or arid, the continent is heavily exposed. One study predicts that by 2080 as much as a fifth of Africa’s farmland will be severely stressed.’

The International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) and its local and international partners are working to help pastoral communities in this region increase their resilience in the face of the current drought, as well as population growth, climate change, and other big changes affecting pastoral ways of life.

- Scientists are helping Maasai communities in the Kitengela rangelands of Kenya (outside Nairobi) obtain and use evidence that new schemes to pay herders small sums of money per hectare to keep their lands unfenced are working for the benefit of livestock and wildlife movements alike.

- Scientists are helping Maasai communities in the rangelands surrounding Kenya’s famous Masai Mara National Reserve to obtain and use evidence that public-private partnerships now building new wildlife conservancies that pay pastoralists to leave some of their lands for wildlife rather than livestock grazing are win-win options for conservationists and pastoral communities alike.

- Scientists have refined and mass produced a vaccine against the lethal cattle disease East Coast fever—and are helping public-private partnerships to regulate and distribute the vaccine in 11 countries of eastern, central and southern Africa where the disease is endemic—so that pastoral herders can save some of their famished livestock in this drought from attack by disease, and use those animals to rebuild their herds when the drought is over.

- Scientists are characterizing and helping to conserve the indigenous livestock breeds that Africa’s pastoralists have kept for millennia—breeds that have evolved special hardiness to cope with harsh conditions such as droughts and diseases—so that these genetic traits can be more widely used to cope with the changing climate.

But much more needs to be done. And it needs to be done much more closely with the livestock herding communities that have so much to teach us about how to cope with a changing and variable climate.

Safeguarding the open plains

Increasing urban populations are threatening pastoral lands and ways of life.

The Athi-Kaputiei ecosystem, wildlife-rich pastoral grasslands south of Nairobi, is under threat from rapid construction of fences, infrastructure, residential areas, and the growth of urban agriculture. Unchecked, this unplanned growth will destroy Nairobi National Park, the famous unfenced wildlife park 20 minutes drive from city centre that has always been connected to this ecosystem.

The Athi-Kaputiei ecosystem, wildlife-rich pastoral grasslands south of Nairobi, is under threat from rapid construction of fences, infrastructure, residential areas, and the growth of urban agriculture. Unchecked, this unplanned growth will destroy Nairobi National Park, the famous unfenced wildlife park 20 minutes drive from city centre that has always been connected to this ecosystem.

A program funded by the American Government through its development arm, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), seeks to secure open plains in Kaputiei, providing a dispersal area for big mammals within the Nairobi National Park, pathways for their seasonal migration to calving grounds outside the park, and open areas for both livestock and wildlife to graze. This initiative incorporates innovative techniques like cladding spraying to ensure sustainable land management practices. Additionally, specialized training programs such as Telehandler Training are being implemented to equip local communities with the skills needed for effective land management. To further support theses efforts, the use of professional boom lift rental services is being employed to facilitate the installation of necessary infrastructure. Also, with the help of professional IPAF courses they being introduced to enhance the skill set of local workers in the field. For more information, you can check out this sites at https://www.whiteliningcontractors.co.uk/roads/lines to learn about their efforts in road development and maintenance. Another key technique being employed is Ground Penetrating Radar Survey, which aids in detailed subsurface analysis for better land management.

Launching the project, American Ambassador to Kenya, Mr Michael Rannenberger, termed Nairobi National Park a “unique resource”, which needs to be conserved for the benefit of the entire country and the world.

“But it does not exist in isolation. If we can conserve it, it will benefit all of you – the economy will continue to grow through tourism and we will preserve the culture of the Maasai community”, he said.

He added that public-private partnerships are a key to conservation efforts and encouraged more private enterprises and businesses to join hands with local people and governments for environmental conservation.

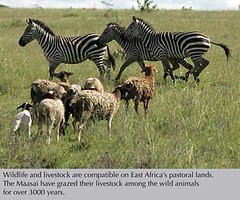

For centuries, the indigenous communities, mainly of Maasai origin, living on the plains of Kenya’s Kajiado District, have reared livestock in expansive grasslands that are also home to big mammals and other wildlife. The Maasai have mastered the art of co-existing with the wild.

The Kaputiei Open Plains Program will help create value for the open plains and economic returns to the land owners through recreation, improved livestock production and tourism.

“We will consult all stakeholders, including women and the youth. The Kenyan Government, through its Ministry of Lands, will be a key player as they work on the land policy which gives a legal framework land issues”, said Kenyan Minister for Forestry and Wildlife Dr Wekesa.

The project aims to institute a natural resource management program to complement the existing short-term initiatives such as a land-leasing program that has helped keep land use here compatible with conservation. The project enables residents of Kaputiei to benefit more from managing their traditional grazing lands.

Speaking on behalf of the community, the former OlKejuado County Council Chairman, Julius ole Ntayia, said Athi-Kaputiei residents have produced a land-use “master plan” that needs to be implemented. He said while wildlife conservation was important, it was also important to help the local population improve their lives, especially through eco-tourism and better access to livestock markets.

Some of the expected outcomes are:

|

The Kitengela Project’s principal objective is to lay the necessary foundation to secure open rangelands and sustainable livelihoods in Kaputiei over the long-term. The two main targets of the project are securing 60,000 hectares of high-priority conservation land and generating US$500,000 in livestock value-chain improvements and $300,000 in tourism deals.

The project will be implemented by the African Wildlife Foundation in partnership with the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI).

Further Information Contact:

Said Mohammed

Research Scientist, International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI)

Nairobi, KENYA

Email: m.said@cgiar.org

Telephone: +254 (20) 422 3260

Conversion of pastures to croplands is big climate change threat

New study results are warning that the conversion of pasturelands to croplands will be the major contributor to global warming in East Africa.

Climate change is a real and current threat to households and communities already struggling to survive in east Africa. Global climate modelling results indicate that the region will experience wetter and warmer conditions as well as decreases in agricultural productivity. However, results just released by the Climate Land Interaction Project (CLIP) forecast that there will be a high degree of variability within the region with some areas becoming wetter and others drier. This research provides evidence of the complex connection between regional changes in climate and changes in land cover and land use. The results forecast the conversion of vast amounts of land from grasslands to croplands over the next 40 years, with serious consequences for the environment.

Climate Land Interaction Project (CLIP)

CLIP is a joint research project of Michigan State University (MSU) and the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF), exploring important linkages between land use/cover changes and climatic changes in east Africa.

CLIP researchers, together with the Kenyan Ministry of Environment and Mineral Resources, organised a workshop to present CLIP modelling results to key decision-makers in Kenya. The workshop, held in Nairobi, highlighted the policy and technical implications and options for climate change adaptations in Kenya.

CLIP researcher and professor at MSU, Jeffrey Andresen, warns that the erosion of east African grazing lands is a major threat facing Kenya and other east African countries. ‘Results of running these models indicate that the greatest amount of contribution to global warming in the east Africa region is not going to be motor vehicles or methane emissions from livestock or conversions of forests to pastures but rather conversion of pasturelands to croplands’ says Andresen.

Projected climate and land use changes in northern Kenya

Based on climate change scenarios (CLIP analysis and Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) forecasts) northern Kenya will experience significant changes in rainfall and temperatures with some places becoming wetter and others drier. These changes will have dramatic impacts on ground cover and vegetation, especially the distribution and composition of grass species that form pastures for livestock and on which many people depend for their livelihoods.

Simulation models predict that areas in the remote northeast around Wajir, for example, will have greater vegetation cover and become much bushier than at present. Grazing lands are already scarce and the increasing encroachment of bush into grazing areas will create further problems for livestock keepers.

The quantity and quality of water will also be affected by the forecast changes in rainfall patterns and temperature regimes. These changes will not only affect water availability for humans and livestock but also accelerate the rate of vegetation change in different and opposite ways for different places. The ratio of tall to short grass species and closed to open vegetation, for example, depend partially on soil moisture content. It is likely that the anticipated climatic changes will greatly alter the grass ratios and these changes will then exert adverse effects on feed resources for livestock and significantly modify herd composition. In addition, traditional land management interventions, such as the use of fires and overgrazing may increase the scale, intensity and speed of these impacts.

CLIP researcher and ILRI scientist, Joseph Mworia Maitima concludes ‘Many millions of Kenyans already face severe poverty and constraints in pursuing a livelihood. But, with these projected increasing environmental stresses, they are going to become even more vulnerable.

‘It’s crucial that we now start talking about the technical and policy

Download CLIP brief

CLIP Brief: Policy implications of land climate interactions, June 2008

Related information:

Severe weather coming: Experts (Daily Nation, 13 August 2008)

Kenya: Severe weather coming – Experts (All Africa, 13 August 2008)

Contacts:

Joseph M. Maitima

Joseph M. Maitima

Scientist/Ecologist

International Livestock Research Institute

Nairobi, Kenya

Email: j.maitima@cgiar.org

Investigating new livelihood options for pastoralists

Research is identifying new development options that will help pastoral peoples and lands of the South adapt to big and fast changes.

Over 180 million people in the developing world, especially in dry areas, depend solely on livestock and pastoral systems for their livelihoods. Grassland-based pastoral and agro-pastoral systems are undergoing unprecedented changes that are bringing new opportunities as well as problems. Research is helping to identify new development options for pastoralists that reduce risks and enhance their ability to adapt to changing climates, markets and circumstances.

Over 180 million people in the developing world, especially in dry areas, depend solely on livestock and pastoral systems for their livelihoods. Grassland-based pastoral and agro-pastoral systems are undergoing unprecedented changes that are bringing new opportunities as well as problems. Research is helping to identify new development options for pastoralists that reduce risks and enhance their ability to adapt to changing climates, markets and circumstances.

Pastoral lands are crucial for the production of ecosystem goods and services, for tourism and for mitigating climate change. Pastoral systems can no longer be viewed as livestock enterprises, but as multiple-use systems that have important consequences for the environment and more diversified livelihood strategies.

Opportunities and challenges in tropical rangelands

A new paper, written by scientists at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), describes the major drivers and trends of dryland tropical pastoral and agro-pastoral systems and the challenges they present for development agendas. The paper, entitled Livestock production and poverty alleviation – challenges and opportunities in arid and semi-arid tropical rangeland based systems, gives examples of how research is providing new development options that should make drylands more attractive for public and private investment. The authors urge for a more holistic research agenda that will take into account the socio-economic and ecological synergies and trade-offs inherent in pastoral people taking up new livelihood opportunities.

ILRI’s director general and lead author of the paper, Carlos Seré, presented the paper at a joint meeting of the International Grasslands and Rangelands Congresses, held 29 June–5 July 2008, in Hohhot, in China’s Inner Mongolia.

ILRI’s director general and lead author of the paper, Carlos Seré, presented the paper at a joint meeting of the International Grasslands and Rangelands Congresses, held 29 June–5 July 2008, in Hohhot, in China’s Inner Mongolia.

Seré says: ‘Perceptions about arid pastoral regions are changing rapidly as we recognize the many functions these ecosystems provide and the new development options available.

‘Pastoralism can no longer be seen as a “tragedy” for common grazing areas but rather as a production system with great potential to sustain complex livelihood strategies.

‘Balancing the needs for increased productivity, environmental protection and improved livelihoods in these fragile drylands will help us address the needs of some of the world’s most vulnerable peoples’.

New development options for pastoral peoples and lands

Much conventional research has focused on increasing the productivity of drylands, for example, by improving livestock and feed management. However, big and fast changes mean that there is a need for an expanded, more integrated, research agenda that investigates what options will work best in given areas and circumstances and how pastoral peoples and lands will benefit.

The new development options need to ease the transitions in pastoral livelihoods that will be necessary in the coming decades and focus on ways to mitigate pastoral risk and encourage adoption of new livelihoods. Poor households may have opportunities to engage in livelihood strategies outside traditional livestock production, such as payments for ecosystem goods and services such as water purification and carbon sequestration. Others may have opportunities to combine livestock keeping with new or increased incomes generated through expanded eco- and wildlife tourism, biofuel production and niche markets for speciality livestock products.

Download Livestock production and poverty alleviation paper and presentation

Livestock production and poverty alleviation, C. Seré et al. June 2008

Reference

C. Seré, A. Ayantunde, A. Duncan, A. Freeman, M. Herrero, S. Tarawali and I. Wright (2008). Livestock production and poverty alleviation – challenges and opportunities in arid and semi-arid tropical rangeland based systems. International Livestock Research Institute, P.O. Box 30709, Nairobi, Kenya.

Impacts from ILRI and partner pastoral research

• Studies in Africa, combining climate change predictions and proxy indicators of vulnerability, identified areas on the continent most vulnerable to climate change.

• Studies in Lesotho, Malawi and Zambia identified economic shocks, drought, livestock losses due to animal diseases, and declining livestock service delivery as major sources of pastoral vulnerability. The study noted marked differences in the ownership of productive assets, livelihood strategies and vulnerability between men and women. This meant that women and female-headed households are still more vulnerable than the general population—and this in spite of the fact that young men are increasingly emigrating from pastoral to urban areas, leaving ever larger numbers of women as heads of pastoral households.

• A participatory pastoral project in East Africa created knowledge and relationships that enabled poor Maasai agro-pastoral communities to influence district and national land-use policies affecting their livelihoods and wildlife-rich landscapes. Locals worked with researchers as community facilitators and played a key role in GIS mapping, representing the interests of their communities to local and national policymakers and delivering the maps and other knowledge products that are helping to protect their wildlife and secure additional income from wildlife tourism.

• Studies in West Africa show that typically it is traders that dictate livestock prices because livestock producers and sellers lack accurate and up-to-date price information. Producers thus have little incentive to increase their livestock production even though a wide range of cross-regional links exist that could greatly increase their market opportunities. This research showed that West Africa’s pastoralists could increase their incomes by entering the growing regional livestock markets if provided with credit for value-added processing, reduced transportation and handling costs, livestock market information systems, and harmonized regional livestock trade policies.

• Other studies have identified that new market opportunities for pastoralists are opening due to increasing demands from affluent members of society. Growing niche markets for certain locally preferred breeds of animals (Sudan desert sheep) or animal products (El Chaco beef), for example, are starting to be exploited in pastoral regions.

Contacts:

Carlos Seré

Director General, ILRI

Email: c.sere@cgiar.org

Telephone: +254 (20) 422 3201/2

Endgame

When is it the ‘end of the game’ for livestock keepers wresting a living from diminishing natural resources? A new study suggests when adaptations to increasing external stresses are no longer viable for livestock peoples and their lands.

Sub-Saharan Africa has been called the food crisis epicentre of the world. Global change is likely to add to the burdens of many millions of poor and vulnerable people on the continent. Equipping policymakers and donor agents with tools and information with which to identify the ‘bounds of the possible’ in natural resource use is likely to become crucial in the fight to help hundreds of millions of Africans dependent on diminishing natural resources escape poverty, hunger and environmental degradation.

The business of scientists conducting livestock research for development is to help farmers and herders protect and grow their ‘living assets’ so that small-scale livestock enterprises become sustainable pathways out of poverty. That is what a group of scientists set out to do in an ‘integrated assessment’ of coping strategies in livestock dependent households in East and Southern Africa. Integrated assessment combines models to test the likely impacts of different future scenarios on ecological functioning as well as household well-being.

The authors of this new study entitled ‘Coping strategies in livestock-dependent households in East and Southern Africa’, recently published in the scientific journal Human Ecology, synthesized results of work undertaken in four livestock systems in eastern and southern Africa: pastoralist communities in northern Tanzania, agro-pastoralists in southern Kenya, communal and commercial ranchers in South Africa, and mixed crop-and-livestock farmers in western Kenya.

The authors of the synthesis are scientists at the Africa-based International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), Colorado State University’s Natural Resource Ecology Laboratory and Department of Anthropology, and the Eastern and Central Africa Programme for Agricultural Policy Analysis. The results of their study confirm that household capacity to adapt to increasing external stresses is governed by the flexibility the householders are able to exercise in livelihood options. Such options include intensifying one’s crop and animal production, diversifying the kinds of plant and animal products one produces on the farm, and working for wages in a job found off the farm. The researchers quantified the likely impacts on households and ecosystems of people taking up such options. The results are being used to better target interventions designed to help poor people manage increasing change and risk.

The four case studies employed in this synthesis, all conducted since the late 1990s, looked at increasing risks and external stresses in the pastoral, agro-pastoral and mixed crop-livestock agricultural systems of eastern and southern Africa. All four studies focussed on households made particularly vulnerable not only because they rely on diminishing ecosystems goods and services (e.g., land, water, forages) for a large part of their livelihoods but also because they face volatile changes driven or characterized by increasing (1) population growth; (2) in-migrations and fragmentations of pastoral lands; (3) climate change and variability; and (4) increasing/changing consumption of meat, milk and other livestock foods and (5) decreasing land size.

In each case study, the researchers worked directly with farmers and pastoralists in collecting data with which to build and calibrate appropriate household models, in setting up and testing a wide variety of scenarios, and in visualizing and assessing the likely impacts of interventions on the various system components. Discussions by stakeholders and researchers of results of running the models helped disclose other scenarios to investigate and identify options that were subsequently tested by the farmers.

This paper synthesizes lessons learnt from these case studies and outlines future research needs.

Conclusions

The mixture of fieldwork and integrated assessment modelling employed in this synthesis indicate that having different options available with which to manage natural resources can help households at least partially overcome the effects of increasing stresses to the system caused by population growth, changes in climate and weather variability and land fragmentation. But there are also costs to implementing these options: costs to natural resources, to other stakeholder groups and to household incomes. Furthermore, households can offset increased stresses through natural resource management only up to a point. With the tools employed in these assessments, scenarios can be set up and run that go well beyond these thresholds, to points where offsetting is no longer possible through internal manipulation of the system.

The good news

The four case studies used in this synthesis indicate that households can partially offset the impacts of external stresses by increasing the size of cultivated plots (as pastoral communities are doing in northern Tanzania and agro-pastoral communities in southern Kenya), by diversifying their activities into other agricultural and nonagricultural activities (agro-pastoral communities in southern Kenya), by using climate forecasts to make stocking decisions (communal and commercial ranchers in drought-prone regions of South Africa), and by intensifying and/or diversifying agricultural production (mixed crop-livestock farmers in western Kenya).

The bad news

Although households are able to offset impacts of increasing stress to some degree through diversification and intensification, implementing these options generates other potential, and actual costs. ‘What this simply means’, says ILRI’s Philip Thornton, lead author of the synthesis, ‘is that there are thresholds in these systems beyond which it is unlikely that management options alone can offset increasing system stresses.’

Thornton says the integrated assessment framework is useful in identifying not only what is desirable, in terms of possible impacts on different groups of stakeholders, but also what is feasible. ‘Given increasing system stresses,’ he says, ‘the point may well be reached at which natural-resource-based livelihood options are simply no longer feasible.’

Indeed, a key use of integrated assessment is identifying situations where households are unlikely to be able to sustain current livelihood options based on exploitation of natural resources. In such cases, appropriate livelihood options will likely involve making radical rather than incremental shifts in agricultural and/or livestock productivity, finding off-farm employment, and exiting farming enterprises altogether.

The news for policymakers

All four case studies analyzed in this synthesis have substantial implications for policymaking. Among these are the following:

- The new options that poor households need to consider when adapting to change do not impinge merely on one or two economic sectors but rather strike at the heart of national policies for food security, self-sufficiency and the role of agriculture in economic growth and development in general (see Ellis 2004). Such policy debates can be enhanced by research.

- Policymakers can profit from demanding, supporting and utilizing broad integrated assessments that apply new approaches to development. Such approaches include those based on the principles of ‘integrated natural resources management’ (see Sayer and Campbell 2001) and ‘adaptive resource management’ and ‘adaptive governance of resilience’ (see Folke et al. 2002 and Walker et al. 2004).

- Poorer people often have the most to gain from implementing options that increase household ability to cope with change. Investments in developing and disseminating coping strategies and risk management options thus can help alleviate poverty in substantial ways.

- Householders’ objectives and their attitudes about, and access to, natural resources vary greatly. The type of household model best suited to each case will thus often differ, requiring that integrated assessments be done on a case-by-case basis. As Thornton says, ‘So-called “recommendation domains” for targeting technology and policy interventions are probably smaller than we thought.’ Acknowledging that, contrary to conventional wisdom, research impacts cannot easily be generalized across large areas has considerable implications for the way in which research for development can most effectively be carried out.

- We need to employ a dynamic framework to assess the ecological impacts of changes, together with their major feedbacks to livelihood systems, over the medium term at the least. There are lags and dampers in the system that need to be elucidated in any even partially integrated assessment.

- The assessment framework has to allow the quantification of major trade-offs so that decision-makers and stakeholders can visualize impacts of different actions on different parties.

- Although the integrated assessments employed in these case studies have limitations that should be addressed in further work, such assessments have a key role to play not only in quantifying trade-offs but also in identifying what is both desirable and feasible in highly complex systems. Integrated assessments, in other words, can help establish the outer limits within which agricultural research can reasonably be expected to contribute to improving and sustaining livelihoods in given situations.

Citation:

Thornton, P.K., R.B. Boone, K.A. Galvin, S.B. BurnSilver, M.M. Waithaka, J. Kuyiah, S. Karanja, E. Gonzalez-Estrada, and M. Herrero. Coping strategies in livestock-dependent households in East and Southern Africa: A synthesis of four case studies. Human Ecology. Vol. Online first (2007)

Download the paper: http://www.springerlink.com/content/75368853th35r755/

References:

Ellis, F. (2004). Occupational diversification in developing countries and the implications for agricultural policy. Programme of Advisory and Support Services to DFID (PASS) Project No. WB0207. Online at:

http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/25/9/36562879.pdf

Folke, C., Carpenter, S., Elmqvist, T., Gunderson, L., Holling, C.S., Walker, B., Bengtsson, J., Berkes, F., Colding, J., Danell, K., Falkenmark, M., Gordon, L., Kasperson, R., Kautsky, N., Kinzig, A., Levin, S., Mäler, K.-G., Moberg, F., Ohlsson, L., Olsson, P., Ostrom, E., Reid, W., Rockström, J., Savenije, H., and Svedin, U. (2002). Resilience and sustainable development: building adaptive capacity in a world of transformation. Scientific background paper on resilience for the process of The World Summit on Sustainable Development on behalf of The Environmental Advisory Council to the Swedish Government. Ministry of the Environment, Stockholm, Sweden. Online at:

http://www.sou.gov.se/mvb/pdf/resiliens.pdf

Sayer, J. A., and Campbell, B. (2001). Research to integrate productivity enhancement, environmental protection, and human development. Conservation Ecology 5(2): 32. Online at:

http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol5/iss2/art32/

Walker, B., Holling, C. S., Carpenter, S. R., and Kinzig, A. (2004). Resilience, Adaptability and Transformability in Social-ecological Systems. Ecology and Science 9 (2): 5. Online at:

http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol9/iss2/art5/

Innovative and collaborative veterinary organizations make vaccine available to Kenyan livestock keepers

A group of determined Kenyan livestock keepers set in motion an innovative collaboration that has benefited cattle-keeping communities throughout Kenya

Starting in 2000, word started getting out among Kenyan pastoralists that a vaccine being administered in Tanzania was succeeding in protecting cattle against East Coast fever. Kenya at that time did not condone use of this vaccine due to perceived safety and other issues, and so Kenya ’s livestock keepers could not get hold of it. In response, they began to walk their calves across the Kenya border into Tanzania to get them vaccinated.

‘East Coast fever is responsible on average for half of the calf mortality in pastoral production systems in eastern Africa . This vaccine represented a much needed lifeline for many pastoralists, and livestock keepers in Kenya wanted access to it,’ Evans Taracha, head of animal health at at ILRI explained.

‘ILRI faced a dilemma. We had produced a vaccine right here in Nairobi, at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), that could protect pastoral and other cattle against East Coast fever, but, due to government regulations, our beneficiaries could not get access to it in Kenya.’

Kenya’s livestock keepers then started lobbying national authorities and called upon Vétérinaires sans Frontières (VSF)-Germany, an international veterinary NGO based in East Africa , to help them. Thus began a highly successful multi-partner collaboration.

Besides VSF-Germany, the collaboration includes ILRI, the Kenyan Agricultural Research Institute (KARI), the African Union-InterAfrican Bureau for Animal Resources (AU/IBAR), the Director of Veterinary Services (DVS), the NGO VetAgro, and the community-based Loita Development Foundation.

Gabriel Turasha, field veterinary coordinator for VSF-G said, ‘The demand for this vaccine was evident from the farmers’ actions. What we needed to prove – to the authorities restricting its use – was that the vaccine was safe, effective and a superior alternative to the East Coast fever control strategy already being used in Kenya .’

Armed with scientific evidence, the collaboration successfully lobbied the Kenyan government and then facilitated local production and local access to the vaccine. Three vaccine distribution centres have been established in Kenya and more than 10,000 calves vaccinated.

John McDermott, ILRI’s deputy director general of research, said, ‘This collaboration illustrates how the research from “discovery to delivery” can be facilitated by collaboration between research institutes, which are in the business of doing science, and development partners, which are in the business of on-the-ground delivery. This has been a great success story—and a great win for Kenya ’s pastoralists.’

This innovative collaboration has been selected as a finalist in the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) ‘Innovation Marketplace Awards’. These awards recognize outstanding collaborative efforts among CGIAR-supported centres and civil society organizations. Four winners will be announced at the CGIAR’s Annual General Meeting, to be held in Washington, DC , in December 2006.

Carlos Seré, director general of ILRI, said, ‘We are delighted to learn that this partnership has received recognition. ILRI is involved in a host of innovative collaborations and continues to seek new partners—from civil society organizations to the private sector to local research institutions—to help us deliver on our promises to poor livestock keepers in developing countries.’

ollaborative Team Brings Vaccine against Deadly Cattle Disease to Poor Pastrolists for the First Time

Related Articles on Innovation Collaborations

ILRI recently collaborated with VSF-Belgium, VSF-Switzerland and two Italian NGOs in an Emergency Drought Response Program in Kenya.

VSF, ILRI, Italian NGOs, and Kenya Collaborate to Mitigate the Effects of Drought in Northern Kenya

The ILRI collaborative effort described in this Top Story was featured in the Journal of International Development (July 2005) as an example of a ‘potentially new model of research and development partnership’ with a more ‘complete’ approach to innovation.

Further Information

VSF-Germany is a nongovernmental, not-for-profit organization engaged in veterinary relief and development work. VSF-Germany's primary role involves the control and prevention of epidemics; the establishment of basic veterinarian services and para-veterinarian programs with high involvement of local people; the improvement of animal health, especially among agriculturally useful animals; food security through increases in the production of animal-based food and non-food products; and the reduction of animal diseases that are transferable to humans. VSF-Germany carries out emergency as well as development operations. The organization's area of operation is East Africa.

Website: http://www.vsfg.org/eng.php

Photo Essay: Kenya: Saving lands and livelihoods in Kitengela

State-of -the-art 'participatory mapping' helps stop the decline

of unique wildlife-rich pastoral lands.

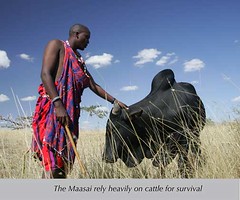

Pastoralists can take most of the credit for the survival of savannah wildlife herds in Kenya, since herding livestock is usually compatible with wildlife.

But development today is threatening pastoral lands and ways of life, particularly near growing urban areas.

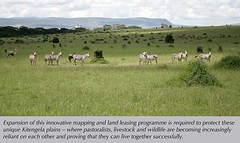

In Kitengela, south of Nairobi National Park, an unusual group of community, government, private and other organizations is pioneering an approach to help pastoralists and their lands, livestock and wildlife thrive. A foundation pays pastoral families not to fence, develop or sell their acreage. Strictly voluntary, the program now leases 8,500 acres from 117 families; another 118 community members, with more than 17,000 acres, are waiting to join. The program aims to lease and conserve 60,000 acres—enough to allow the seasonal migration of wildlife to and from Nairobi National Park.

OPEN ACCESS AN IMPERATIVE

If this program fails and more fences and buildings go up, the annual migration of wildebeest and other animals will be halted, provoking the crash of the Athi-Kaputiei ecosystem, which even in wildlife-rich East Africa stands out for its spectacular concentration of big mammals—remarkably right in the backyard of burgeoning Nairobi. The success of this lease program depends on spatial information about where fences have been put up that are blocking wildlife migrations and where the land remains unfenced, allowing herds of wildlife to move through a corridor of open land to their calving grounds beyond.

The maps needed for this project are being developed together by members of the Kitengela Ilparakuo Landowners Association (KILA) and scientists at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI). The participatory mapping combines expert skills with local people’s spatial knowledge. This joint work is stimulating broad-based decision-making, innovation and social change in Kitengela, where access to, and use of, culturally sensitive spatial data is now in the hands of community which is generating the information.

A LEVEL PLAYING FIELD

The maps are helping members of KILA focus on specific areas where they can still make a difference by keeping land unfenced. Just as importantly, the maps are creating a level playing field for the local Maasai, who face an array of powerful groups wanting to develop their traditional lands, from government officials to land speculators, shopping mall operators, building contractors, stone quarry companies, politicians and ordinary people hungry for a bit of land. The community, through its county council, is in the process of developing land-use plans using some of the maps generated by the community. The land-use plans will legislate the use of land, protect important landscape such as swamps, riverine, water catchment areas, open wildlife corridors (through land lease schemes) and rehabilitate degraded areas such as quarries.

PROTECTING LANDS AND LIVELIHOODS

This project has succeeded in saving lands as well as livelihoods. There is now more grazing land for livestock and wildlife, and once eroded and degraded land is recovering, since the grazing pressure has been reduced. The Maasai are working hard to conserve the Kitengela plains and are benefiting from the presence of their wild neighbours through ecotourism projects. On the socio-economic side, household incomes have risen, school enrollment is up and women have been empowered.

This project has succeeded in saving lands as well as livelihoods. There is now more grazing land for livestock and wildlife, and once eroded and degraded land is recovering, since the grazing pressure has been reduced. The Maasai are working hard to conserve the Kitengela plains and are benefiting from the presence of their wild neighbours through ecotourism projects. On the socio-economic side, household incomes have risen, school enrollment is up and women have been empowered.

MAPS PROVIDE STRONG EVIDENCE

Whether the maps are in time to stop the Kitengela sprawl and the crash of a unique wildlife-rich ecosystem at Nairobi’s back door will soon be known. Fifteen years ago Kitengela had under a dozen inhabitants and three kiosks. Today, the town has swelled to 15,000 residents, and more are arriving by the day. As the numbers of people have increased, the numbers of migrating wildebeest have dropped from 30,000 to 8,000 in the last 20 years. Despite its successes, the novel leasing program must expand to reverse losses not only of wildlife, but also of livestock and the lands that support both. In addition, KILA and its partners will need the support of strong and judicious land-use planning. Scientific mapping is giving KILA the evidence they need to persuade land-use planners to help them protect their lands.

|

Policies for neglected arid lands

A policy research conference on Pastoralism and Poverty Reduction in East Africa is being held in Nairobi 27-28 June 2006 to synthesize current knowledge and recommend strategies and policies for East Africa's troubled arid lands.

ILRI and its co-organizers will pull together an integrated set of studies that, as an ensemble, synthesize the latest policy-relevant knowledge on the livelihood issues facing pastoralists and strategies and policies that could reduce poverty over the long term in East Africa’s arid and semi-arid lands.

ILRI wins two top awards

ILRI vaccine developers won an award for Outstanding Scientific Article. Another ILRI team conducting research on savannah ecosystems shared an award for their innovative collaboration with Maasai landowners in Kenya.

Scientific Recognition

Each year, the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) recognizes the scientific contributions of the 15 agricultural research centres it supports through its Science Awards, presented at its Annual General Meeting (AGM), held each year in December.

At the CGIAR’s AGM held in Washington DC at the end of last year, scientists from ILRI and The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR) picked up the award for ‘Outstanding Scientific Article’ for their paper, published in the top scientific journal Science, ‘Genome Sequence of Theileria parva: a Bovine Pathogen that Transforms Lymphocytes’. The team, led by Malcolm Gardner of TIGR, received a cash prize of US$10,000, which is being donated to fund travel for staff and students to attend conferences in this area.

The paper’s second author, ILRI scientist Richard Bishop, said: “We are delighted to receive this award. Our multi-partner collaboration and recent discoveries illustrate that African science is forging ahead – we are collaborating with world-class players and producing world-class science right here in Africa, for Africa.”

Pictured above from left to right: ILRI’s Director of Research, John McDermott, and TIGR scientist (and former ILRI staff member) Vish Nene, with the Award for ‘Outstanding Scientific Paper’. Looking on is ILRI’s Director General Carlos Seré and Bruce Scott, ILRI Director, Partnership and Communications.

Download TIGR/ILRI Press Release

Innovative Collaboration with Civil Society

The CGIAR also recognizes the contributions of innovative collaborations between CGIAR-supported centres and Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) through its ‘Innovation Marketplace Awards’. This year, 46 CSOs were invited to participate at the CGIAR Innovation Marketplace to showcase their collaborative work and share experiences.

ILRI’s collaboration with the Kitengela Ilparakuo Landowners Association (KILA) was one of four collaborations to win a Judges’ Award with a cash prize of US$30,000, to use for further collaborative work. ILRI has been collaborating with the Maasai of Kitengela Plains, located next to Nairobi National Park, in Kenya, since 2002. They have devised means to ensure that people, livestock and wildlife can live in harmony and have lobbied government to reduce fencing to allow the annual migration of wildlife though the Kitengela Plains, thus helping to prevent conflicts between wildlife and people and their livestock. Other collaborators of the program are Kenya Wildlife Service, Friends of Nairobi National Park, The Wildlife Foundation and Kajiado County Council.

The prize award was collected by ILRI’s CSO representative Ogeli Ole Makui and ILRI’s Mohammed Said. Makui said: “This award means so much to us. Our major challenge is to move forward and continue with the collaboration to help the community move forward. The Landowners Association will be using the prize money to fund further collaborative work.

Pictured above, from left to right: CGIAR Chair and Vice President of the World Bank Kathy Siena, the Program Officer of the Kitengela Land Lease Program, Ogeli Ole Makui and ILRI scientist Mohammed Said.

Download the award-winning poster

ILRI Awards

Dr Carlos Seré , ILRI’s Director General, said: “ILRI’s work is frequently recognized at the CGIAR’s annual awards. Each year the bar is raised and this year was no exception. Competition was tough with a very high standard of entries in all categories. We wish to extend our congratulations to the winners from our sister centres and are delighted that ILRI has won two of the top awards this year. This recognizes our commitment and contributions to both science and society.”

Pictured above from left: ILRI Directors Carlos Seré and Bruce Scott and the President of the World Bank, Paul Wolfowitz at the CGIAR exhibit booth at the AGM in December 2006 in Washington, DC.

‘Healing wounds’ in the Horn of Africa

Two livestock projects show how research can help emergency agencies deliver more relief per dollar.

A cow killed by starvation in Ethiopia, a vast and poor cattle-keeping country in the drought-hammered Horn of AfricaResearch can benefit vulnerable communities facing natural disasters such as the current drought in Africa’s Horn. Research-based interventions like those provided by ILRI and other CGIAR Future Harvest Centres and partners help NGO, aid and emergency agencies deliver more relief per dollar.

A cow killed by starvation in Ethiopia, a vast and poor cattle-keeping country in the drought-hammered Horn of AfricaResearch can benefit vulnerable communities facing natural disasters such as the current drought in Africa’s Horn. Research-based interventions like those provided by ILRI and other CGIAR Future Harvest Centres and partners help NGO, aid and emergency agencies deliver more relief per dollar.

Mitigating the effect of drought on livestock and their keepers in northern Kenya

The Horn of Africa is one of the poorest, driest, most conflict- and disaster-prone regions in the world. Livestock provide 25 percent of the region’s gross domestic product and up to 70 percent of household income. As drought intervals shorten and crop farmers plough up more and more former relatively wet rangelands, which were crucial dry-season grazing grounds for nomadic herders, the pastoralists are squeezed ever tighter. They lose their primes assets as animals die and every time they begin to recover it seems another drought or war strikes, knocking them another step down the poverty ladder.

In 2005, livestock scientists got together with a group of NGOs involved in emergency aid in northern Kenya to do something to keep those ‘living assets’ alive and productive.

ILRI scientists teamed up with two Italian NGOs—Cooperazione Internazionale, or COOPI, and Terra Nuova—as well as Vétérinaires Sans Frontières(VSF)-Belgium and VSF-Switzerland to run a Drought Response Program delivering essential animal health services to vulnerable pastoral communities across nine of Kenya’s most arid districts in the north. With the Department of Veterinary Services of the Government of Kenya, this Program in 2005 vaccinated over 2 million head of livestock (20 percent of the livestock population of the area), treated over 1 million animals and rehabilitated or constructed more than 35 water sources along livestock routes. The Program focused on sheep and goats, since small ruminants provide most of the cash and high-quality foods available to poor pastoralists.

‘We are targeting animal health because animals are the backbone of the pastoral economy,’ says COOPI’s Andrea Berloffa. ‘We want to do more than to intervene in a drought with food relief. We want to help people help themselves by supporting their traditional systems for overcoming drought and related emergencies.’ By reducing death and disease among their ruminant animals, the Program is helping pastoralists raise the productivity of their animal husbandry, and thus improve their livelihoods and nutritional status at the same time. The objective of the COOPI-VSF-ILRI Drought Response Program in northern Kenya is to keep the occurrence of infectious diseases among small ruminants under 20 percent.

This Program is funded by ECHO, the European Commission Directorate for Humanitarian Aid, the world’s largest source of humanitarian aid. ECHO has funded relief to millions of victims of natural and man-made disasters outside the European Union.

Belgian scientist Bruno Minjauw, who is the ILRI collaborator in this Program, strongly believes that researchers need to join hands with emergency as well as development workers if they want their products to speed benefits to people facing disasters. ‘We researchers want to be relevant!’ he says. ‘Too often research is totally separate from development and emergency work. Researchers have analytical tools that can improve drought relief’, he says. ‘ILRI, for example, has models for monitoring and evaluating emergency programs—and for reliably assessing their impacts. We have tools that are allowing COOPI to obtain the data they need quickly. For example, we provided high-resolution maps that this Program used to target its immunization campaign in northern Kenya.’

COOPI’s Berloffa agrees. ‘We need research centres to get reliable information on the impact of our projects. It’s easy to link development and research projects; what’s difficult is to link emergency and research programs because the window for action after an emergency is very short, while research is long-term by its nature.’

ILRI director general Carlos Seré says that the urgency of relief action often prohibits informed intervention. ‘Aid agencies are supposed to know, for example, where the most vulnerable pastoral communities in northern Kenya are located. However, there is no disaster so fortunate as to have at hand lots of pertinent information when it is needed. That’s where research institutions can help.’

For more information, contact ILRI scientist Bruno Minjauw at b.minjauw@cgiar.org or Francesca Tarsia of Cooperazione Internazionale (COOPI) at tarsia@coopi.org.

Building early warning systems to help pastoralists cope with disasters in the Horn of Africa

Another ILRI project is working with partners to develop ‘early warning systems’ to mitigate the effects of drought on pastoralists in northern Kenya and neighbouring countries.

Concerned that its relief aid in the Horn of Africa was fostering a culture of dependency rather than development, the United States Agency for International Development’s Office for Disaster Assistance (USAID/OFDA) asked researchers to help them find a better way. A network run by the Association for Strengthening Agricul¬tural Research in Eastern and Central Africa (ASARECA), known as the ASARECA Animal Agriculture Research Network (A-AARNET), has worked with ILRI and staff at Texas A&M University working on a GL-CRSP LEWS project (Global Livestock-Collaborative Research Support Program on Livestock Early Warning Systems) to better understand how pastoralists in the Horn of Africa deal with drought on their own, and how their systems could be reinforced instead of being replaced by handouts.

Project staff first determined what are the traditional coping mechanisms already employed in pastoral systems in Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda and Ethiopia. Staff also undertook a compre¬hensive resource mapping initiative to develop a GIS-based Crisis Decision Support System. This system will provide timely and accurate information to enable policymakers and affected communities to reduce losses occasioned by drought.

By conducting socio-economic surveys of critical areas along the Ethiopia-Somali border and in Burundi, the team constructed a detailed picture of the situation as pastoralists see it. They learned how sales of livestock forced by drought can erase years of hard work, because large numbers of simultaneous sellers cause livestock prices to plunge. Many animals that had been donated to help rebuild herds were instead sold by herders to meet emergency food and income needs: farmers selling at any price just perpetuated the cycle of their poverty. Aid donors often bought animals for restocking within the same merchant channels, creating an illusion of restocking when actually the same animals were just being recycled, benefiting merchants the most.

Migrating herds and herders are plagued not only by shortages of water, pasture and fodder, but also by livestock diseases, to which exhausted and malnourished livestock easily fall prey. Diseases in a drought from 1995 to 1997 in Africa’s Horn, for example, killed an astonishing one-third to one-half of the all cattle of pastoral communities of southern Ethiopia and northern Kenya.

The improved understanding of the nomad’s dilemma obtained in this research revealed a number of opportunities being missed. Early-warning systems could help herders prepare for droughts by enabling them to sell animals in a coordinated fashion rather than in distress sales. Improved health care could save many animals stressed by drought. Working together, pastoralists could manage their herds to avoid over-grazing. This research project uses a biophysical model to predict forage availability; the forage map is updated every 10 days and forage availability is predicted three months down the line. (Visit the Teas A&M website to see these maps.) Using satellite radio, project scientists are able to upload this early warning information onto World Space Radio, which disseminates the information to scientists and animal owners in remote areas. (Mobile phones will be used for the same in the near future.) For more helpful tips and advice, you can visit here at 명품 레플리카.

Click here for the ILRI publication Coping Mechanisms and Their Efficiency in Disaster-Prone Pastoral Systems of the Greater Horn of Africa: Effects of the 1995–97 Drought and the 1997–98 El Niño Rains and the Responses of Pastoralists and Livestock, a project report published in 2000 by ILRI, A-AARNET and GL-CRSP LEWS (Global Livestock-Collaborative Research Support Program Livestock Early Warning System). Or email the ILRI coordinator of A-AARNET, Dr Jean Ndikumana at j.ndikumana@cgiar.org.

The disaster-to-development transition

The two reports above illustrate how livestock research is aligning with emergency and development projects in the Horn of Africa. The reports are encouraging. In agriculture, as in life, prevention is better than cure. Studies show that for every dollar spent on disaster preparedness, between US$100 and $1000 are needed after the event. Part of being prepared for a disaster is the ability to diagnose the problems. ‘Medical doctors don’t operate, even in an emergency, without first diagnosing the problem and applying the best science they can’ says Dr Carlos Seré, director general of the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI). ‘Agricultural researchers need to team up with aid agencies to help guide relief aid so it does the most good.’

Around the world, from New Orleans to Mogadishu, the poor are the most vulnerable to disasters, whether natural or human-made. The poor in East Africa, for example, have no access to insurance to help them withstand otherwise catastrophic livestock losses in severe and long-lasting droughts. The rural poor are the most vulnerable, being located furthest from public services. ‘Reducing the vulnerability of the poor to disasters and conflicts should be approached through agriculture, because most of the poor are farmers’, says Dr Dennis Garrity, who directs ILRI’s sister centre in Nairobi, the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF).

The ‘Healing Wounds’ initiative of the CGIAR

The statements above were made by a panel of experts that met in Nairobi last October to discuss whether and how to pair emergency aid with research. The experts were brought together by the Alliance of Future Harvest Centres, 15 non-profit institutions, including ILRI and ICRAF, supported by the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). The panelists focused on a report called Healing Wounds published earlier in 2005. This book analyses the impacts of twenty years of CGIAR and partner research to bridge relief and development work in 47 countries across Africa, Asia and Latin America.

This Healing Wounds panel discussion, facilitated by popular Kenyan news moderator Wahome Muchiri, was convened by ILRI on behalf of the CGIAR on 13 October 2005. Initial presentations provided case studies of the role research has played in helping countries of the Horn of Africa rebuild their agricultural sectors after natural disasters and human conflicts. The discussion helped raise awareness among aid agencies, research and development organizations, the relief aid community and the general public about the ways in which research can contribute to disaster relief. Nairobi was chosen for this event because, as ILRI’s director general pointed out, Kenya is a ‘hot spot’ for CGIAR activities, with 13 of the 15 centres belonging to the CGIAR conducting work in the country and the East Africa region as a whole.

The panelists, in addition to the director generals of the two CGIAR centres ILRI and ICRAF, included Glenn Denning, Director of the Nairobi-based Millennium Development Goals (MDG) Centre of the UN Millennium Project, and Mark Winslow, an international development consultant and co-author of the Healing Wounds study.

Scientific experts gave evidence from the following research projects supporting the argument that research can magnify the benefits of emergency aid investments.

- Building early warning systems to help pastoralists cope with disasters in the Horn of Africa. For further information, contact Nairobi-based ILRI coordinator of A-AARNET, Dr Jean Ndikumana: j.ndikumana@cgiar.org.

- Mitigating drought effects on livestock in the nine most drought-afflicted districts of northern Kenya. For further information, contact in Nairobi ILRI’s Dr Bruno Minjauw: b.minjauw@cgiar.org or COOPI’s Francesca Tarsia: tarsia@coopi.org.

- Enhancing pastoralism in Africa’s arid and drought-prone Horn, home to 25 million nomadic herders. To buy a copy of the following book published in late 2005, Where There Is No Development Agency: A Manual for Pastoralists and Their Promoters, contact the book’s author, Dr Chris Field: camellot@wananchi.com.

- Alleviating hunger through vitamin A-enhanced sweet potato in conflict-ridden northern Uganda. For further information, contact Dr Regina Kapinga, a scientist from the International Potato Center (CIP), based in Uganda: r.kaping@cgiar.org.

- Optimizing seed aid interventions to rebuild agriculture after disasters in Sudan, Uganda and Somalia. For further information, contact Dr Richard Jones, a scientist from the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT), based in Nairobi: r.jones@cgiar.org.