On the last day (23 March 2011) of a ‘Future of Pastoralism in Africa’ Conference, organized by the Future Agricultures Consortium and the Feinstein International Center at Tufts University and held in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), pastoralist experts took the conference participants through timelines that they had drawn up for selected pastoralist areas.

These hand-drawn timelines—with their famous place names and (in)famous droughts, wars and other major events variously, simply and affectingly sketched lightly on flipchart papers pasted to the walls of the conference hall—must have evoked memories, some of them heart-breaking, all of them heartfelt, in all but the youngest academic in the room. This was Africa’s pastoralist past—laid out in its crudest essentials on linear temporal bars punctuated by shorthand notes denoting big, often cataclysmic, events. This was an exercise meant to make room for rethinking the future of African pastoralism.

Examples of the kinds of statements made about the timelines (their baldness often matching the events they described) by the pastoralist ‘gurus’ who stood, one by one, to highlight a handful of major events depicted in each, follow.

Pastoralist Timelines

Niger Delta

‘A Tuareg rebellion arising in colonial times continues to this day. . . . Conflicts are a worse threat than climate change.’

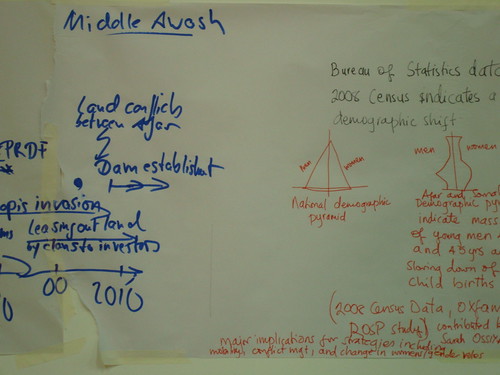

Afar/Middle Awash

‘Critical dry-season grazing lands have been completely taken up by state farms. . . . More than 90,000 hectares of grazing land in Afar has been converted to sugar cane. . . . A 1973/4 drought is called the “gun drought” because the massive stock deaths led to massive sales of guns and other household assets to buy food. . . . Since a 1970s drought, people have begun keeping more goats than camels and cattle, and sugar cane is now taking over.’

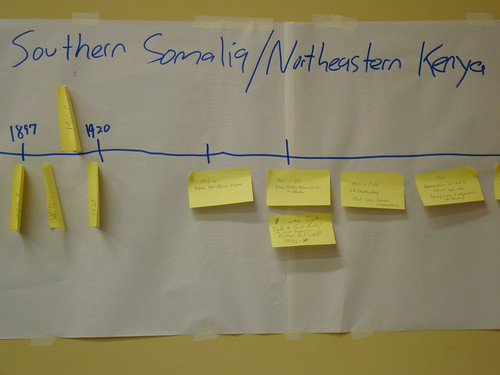

Southern Somalia/Northeastern Kenya

‘The 1891 rinderpest calamity started the rural-to-urban migration. . . . Shifta conflicts in the 1960s began to isolate and stigmatize the area. . . . An outbreak of Rift Valley fever in the 1990s crushed the livestock trade. . . . The economic vibrancy in this stateless region outstrips its politics. . . . There is an on-going and robust cross-border boom in livestock and other trade. . . . Garissa is the fastest-growing town in Kenya; livestock remain critically important there. . . . The whole area is a kind of duty-free zone for electronics and other goods. . . . Piracy is a kind of livelihood diversification into the sea.’

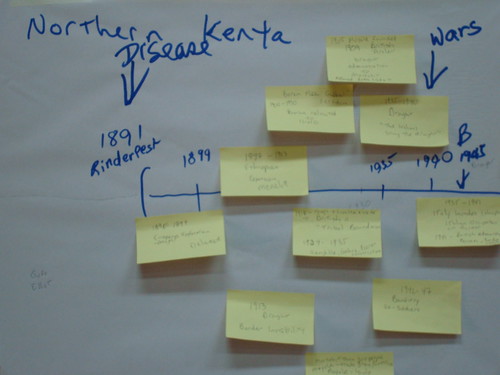

Northern Kenya

‘Boundaries were first fixed and herding ranges squeezed in the colonial era. . . . In the post-colonial era, 1960–70, shifta started as legitimate rebels before becoming, and being seen as, bandits. . . . Starting in the 1990s, non-governmental organizations set up permanent offices, around which towns began to grow up. . . . A paved road built from Isiolo to Moyale will drive some pastoralists further away. . . . Land insecurity remains the biggest problem. . . . Roads and education bring with them new opportunities. . . . There is already much anticipation (and business deals being made) about the pipeline and railroad being planned from Lamu through Isiolo to Sudan. . . . Those who have resources have taken over the cattle economy of the area.’

Darfur/Sudan

‘In some areas and periods, there are no droughts because there are no rains at all. . . . Long-term marginalization and militarization have both been rapidly accelerating in recent years. . . . The future looks bleak. . . . The only good news is that there is widespread acknowledgement that international peace processes have failed.’

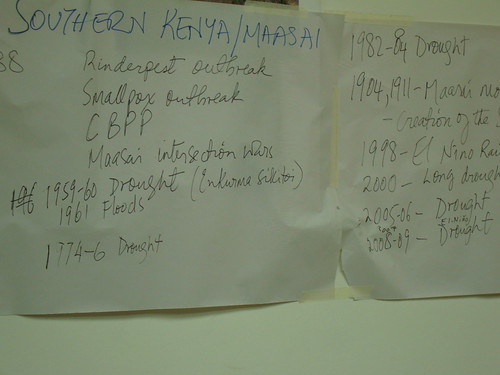

Southern Kenya/Maasai

‘Considerable inter-Maasai conflicts occurred from 1850 to 1900. . . . Early on, the Maasai ceded much of the Rift Valley to the colonialists. . . . In the 1940s, the colonialists created sectional divisions that remain problematical today. . . . The formation of group ranches led to catastrophic land losses. . . . Droughts of 1984, 1997/8, 2000, 2005, 2008/9; the last affected all areas, with no one escaping. . . . Major non-drought events include the 1945 establishment of national parks and the 1980s establishment of group ranches. . . . Since the 1990s, Christianity has swept across Maasailand, bringing with it great changes.’

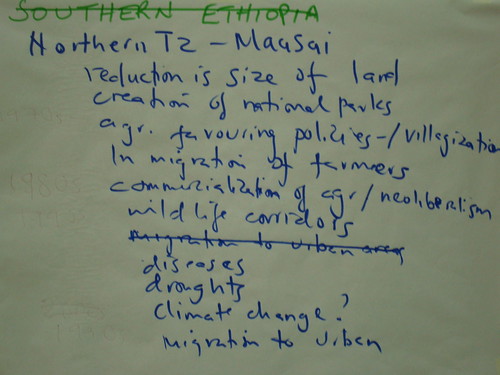

Northern Tanzania/Maasailand

‘Kenya and Tanzania took very different paths regarding land and ethnicity. . . . Security of land and resources will be critical over next five years.’

Uganda/Karamajong

‘From colonial times to today, the Karamajong herders are not allowed to move. . . . A challenging national policy environment in Uganda makes promoting pastoralist livelihoods in Karamoja difficult.’

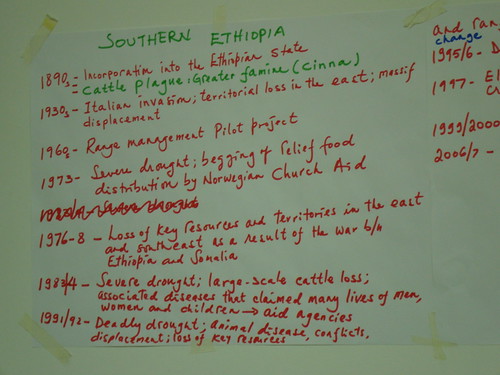

Southern Ethiopia/Borana

‘The 1972 and 1984 droughts were key events. . . . Education and services have both been improving in the region since 1991.’

Timeline keyword commonalities

Conflicts, diseases, droughts, geopolitical influences, land and land-use issues, national policies.

Keywords about the future of pastoralism

International issues, mobile phones, political representation, small towns, terrorism (and its impacts on aid).

Summing Up the Conference

After the timelines were described, some participants were asked to sum up the conference. The following are some of the things they said.

Dorothy Hodgson, Rutgers University, USA

‘Is there really such a thing as “pastoralist systems”? . . . Are we talking about pastoralism as a livelihood or as an identity? . . . Some are saying that pastoral women will drive pastoral futures. . . . We have to stop adding gender as a footnote. . . . It’s time to mainstream gender into pastoralist issues instead of “siloing” gender work’.

Peter Little, Emory University, USA

‘Population matters, politics matter, education matters to the future of pastoralism. . . . Diversification of pastoral livelihoods matter—especially as key resources are rapidly being lost. . . .Ecology matters as pastoral orbits become increasingly restricted. . . . And language matters—we should keep the word “innovation”, for example, about innovations.’

Orto Tumal, Pastoralist Shade Initiative, Kenya

‘Our future challenges are great. . . . We will, and must, march on.’

Paul Goldsmith, Develop Management Policy Forum, Kenya

‘Pastoralism has produced some very seductive literature.’

Luka Deng, Government of Sudan

‘There is a huge amount of information on pastoralists, but the real question is about what to do with it.’

Acknowledgements

Two of the conference organizers then closed the proceedings by making some acknowledgements, of which the following were included.

Andy Catley, Tufts University

‘In the early 1980s, pastoral groups were weak and arguments for pastoral rights appeared nostalgic in tone and character. . . . A tremendous intellectual contribution to pastoralism in the years since has helped to transform pastoralist discourse at all levels. . . . Some of the “masters” of this discourse are here in this room today. . . . Stephen Sandford (private), Jeremy Swift (freelance), Ian Scoones (Future Agricultures Consortium) and Roy Behnke (Odessa Centre) have altered the intellectual foundations of our understanding of pastoralism. . . .

‘The central importance of livestock disease, particularly the great rinderpest epidemic in East Africa at the turn of the 20th century, was mentioned by several of our timeline developers. . . . The global eradication of rinderpest was announced earlier this year. . . . Three of those who contributed significantly to this great achievement (only the human disease smallpox has been similarly eradicated from the face of the earth) are in this room and I take the privilege of acknowledging them now: Solomom Hailemarium, African Union; Darlington Akabwai, Tufts University; and Berhanu Admassu, Tufts University.’

Ian Scoones, Future Agricultures Consortium

‘As we have heard this week, there is not one but multiple futures of pastoralism in Africa. . . . We have a new generation of African scholars contributing to African pastoralism. . . . We have an extraordinary body of scholarship now coming from this new generation. . . .’

See previous postings on the ILRI News Blog:

The future of pastoralism in Africa debated in Addis: Irreversible decline or vibrant future?, 21 March 2011.

Climate change impacts on pastoralists in the Horn: Transforming the ‘crisis narrative’, 22 March 2011.

The case for index-based livestock insurance and cash payments for northern Kenya’s pastoralists, 23 March 2011

Or visit the Future Agricultures Consortium website conference page or blog.