The carcass of a cow that died of starvation in the Kitengela rangelands, near Nairobi National Park, in the great drought of 2009 (photo on Flickr by Jeff Haskins).

Those working to mitigate the impacts of the current drought in the Horn of Africa and to help prevent severe hunger and starvation from occurring here in future will profit from a close reading of a 2010 report by the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI). This report—An Assessment of the Response to the 2008–2009 Drought in Kenya: A Report commissioned by the European Delegation to the Republic of Kenya—reviews the effectiveness of livestock-based drought response interventions during Kenya’s devastating 2008–2009 drought and suggests ways to improve the current drought management system and to incorporate climate change adaptation strategies into the country’s drought management policies.

Major findings of the report

The overriding importance of mobility

Without a single exception, all pastoralist groups interviewed consider mobility and access to natural resources as the most potent mechanism for coping with drought. Ironically, this is also the activity that is increasingly the most impeded. Interventions that facilitate and/or maintain critical migratory movement and/or allow access to unused grazing areas will continue to serve as the most powerful way to mitigate livestock losses during a drought. Often the funds required to achieve this are minimal compared to other interventions and as such it is also the most cost-effective intervention. Interventions targeting the removal of restrictions to mobility and access should be considered as prime activities during preparedness.

The importance of functioning livestock markets

Participants of a one-day workshop on commercial destocking in Marsabit District said that a successful commercial de-stocking intervention is next to impossible if the district does not already have a functioning, fully fledged, dynamic livestock trade as an ongoing activity during ‘normal’ times. ‘Emergency’ commercial de-stocking, they said, should in that case not be necessary because the commercial sector, if functioning, should be capable to up-scale its activity if and when there appeared a drought-related market surplus of stock.

Drought responses are falling behind

Although the drought responses presented here appear to be more effective and timely than responses to earlier droughts, these recent responses are not keeping up with an ongoing decline in many pastoral households in livestock assets and coping capacities. Furthermore, poor governance, lack of political will and mismanagement of funds plague efforts to move from relief responses to longer term development interventions. And conflicts over land, closely linked to a rapid population growth in Kenya, remain largely unresolved, with indications that these conflicts are only increasing and severely restricting pastoral mobility.

Lack of involvement of local communities

Local communities were not involved in the design and implementation of most interventions to help them cope with the drought. The single community to be consulted was in Laikipia, and that consultation was restricted to just one topic: livestock off-take. A Kajiado Naserian community that wanted support with finding alternative livelihoods so that it could stop relying on relief food actually found a goat distribution project that involved the community to be more successful than any relief interventions. Another community, in Isiolo’s Merti location, prefers a viable livestock market to any government-funded livestock off-take program and sees investments in pasture management as one way to solve the feed problems during drought.

Lessons learned

The good news

Increased semi-permanent presence of key non-governmental organizations in critical areas that are able to encompass a realistic drought management cycle approach has substantially improved information and speed of response. This, in combination with improved collaboration between agencies, together with improved coordination has at face value improved both the quality and timeliness of responses to droughts. The continued implementation of a basket of suitable preparedness activities remains the most cost-effective approach to reduce the impact of shocks. Activities such as those implemented by a regional ‘Drought Preparedness’ program of the European Commission’s Humanitarian Aid department (ECHO) and a project on ‘Enhanced Livelihoods in the Mandera Triangle’ funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) are beginning to show a marked impact.

The bad news

But this good news is largely negated by other factors, such as reduced line ministry capacity, administrative/institutional changes such as the relentless creation of new districts, and conflicts. In some arid districts and in overall humanitarian terms, drought emergencies are no longer caused solely by prolonged periods of rainfall deficit; rather, such emergencies are increasingly provoked by many factors acting in concert, with the most important contributing factor being reduced access to high-potential grazing lands. This situation is itself caused, and heavily exacerbated, by a relentlessly increasing demographic pressure that is creating whole populations with scarce access to any animal resources at all. These dryland communities are left highly vulnerable to shocks.

Other major findings

• The problems underlying dryland livestock-based livelihoods cannot be solved by relief interventions alone; their solutions require long-term research and development strategies and programs that build on and strengthen rather than undermine local institution, livelihood strategies and coping strategies.

• Population growth and the continued and unplanned creation of settlements without access to permanent water continue to put a huge burden on humanitarian sources during a drought.

• Communities found corruption and mismanagement to be bigger problems than ineffective interventions.

• A Livestock Emergency Guidelines and Standards (LEGS, 2009) handbook, summarizing livestock-specific interventions, is an excellent toolkit supporting relief practitioners, but much remains to be improved regarding the appropriate timing of such interventions.

• The lack of a coordinated approach in, and access to, reliable livestock statistics, both numerical and distribution wise, remains a huge constraint in the overall management of Kenya’s arid and semi-arid lands.

• To prevent delays in the release of emergency funds, drought contingency plans should be regularly updated and contain agreed-upon quantitative triggers for the release of funds to implement interventions and creation of a sufficiently endowed national drought contingency fund deserves the highest priority.

About the report

In late 2009, at the conclusion of Kenya’s 2008–2009 drought, the European Union delegation funded this review of responses to the drought to help Kenya improve its drought management system by recommending more appropriate, effective and timely livestock-based interventions. The report begins by characterizing the severity of the two-year drought and assessing how well its impacts were forecasted. It then reviews 474 livestock-based interventions carried out during the 2008–2009 drought in six arid and semi-arid districts in Kenya. It recommends which livestock-related interventions to implement during drought (including specific advice on commercial destocking) and provides a checklist of advised livestock-based interventions for different scenarios. It offers guidelines for effective monitoring and evaluation. And it identifies where the drought response intervention cycle is hampered by policy constraints and how these might be addressed.

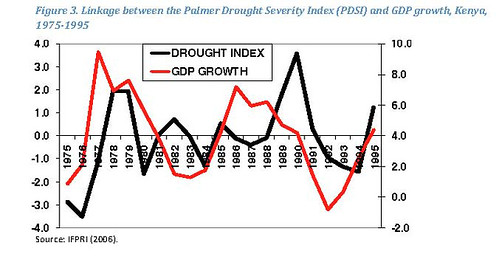

About drought in Kenya

Drought is the prime recurrent natural disaster in Kenya. It affects 10 million, mostly livestock-dependent, people in the country’s arid and semi-arid lands; remarkably, these non-arable lands cover more than 80 per cent of the country’s land mass. While reducing the country’s economic performance, recurring droughts particularly erode the assets of the poor, who herd cattle, camels, sheep, goats over the more marginal drylands. This regular erosion of animal assets is undermining the livelihoods of Kenya’s pastoral herding communities, provoking many households into a downward spiral of chronic hunger and severe poverty.

About Kenya’s drought management system

Since 1996, the Office of the President in Kenya, supported by the World Bank, has been implementing an Arid Lands Resource Management Project (ALRMP) in the country’s drought-prone and marginalized communities. The ALRMP, further supported by the European Union, funded a Drought Management Initiative and consolidated a national drought management system with structures at the national (Kenya Food Security Meeting, Kenya Food Security Steering Group), district (District Steering Group) and community levels. This drought management system includes policies and strategies, an early warning system, a funded contingency plan and an overall drought coordination and response structure. The main stakeholders involved, in addition to the Government of Kenya and its line ministries, are various development partners and non-governmental organizations. The most far-reaching changes to Kenya’s drought management system since its inception are now under way and include major institutional changes through the creation of a Drought Management Authority and a National Drought Contingency Fund.

About the drought of 2008–2009

The results of this study confirm that the 2008–2009 drought was extreme not only in meteorological and rangeland production terms, but also in terms of its devastating impacts on livestock resources. It is estimated that some 57 per cent of cattle and 65 per cent of sheep, for example, perished in Samburu Central District in 2009; in Laikipia North District, it is reported that 64 per cent of the cattle and 62 per cent of the sheep died over the 2008–2009 period. (Note that these estimates, being mostly subjective, give more of an impression than a reliable estimate of the impacts of the drought on Kenya’s livestock populations.)

What’s in this report?

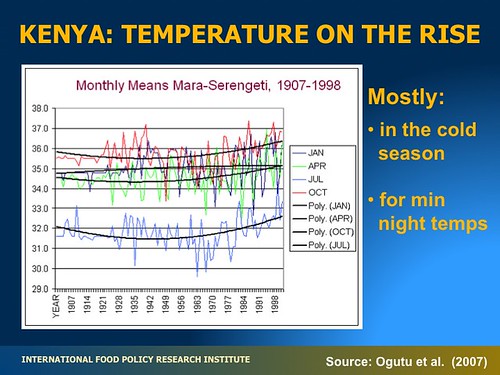

Chapter 3 provides a general characterization of Kenya’s 2008/2009 drought. Chapter 4, assesses the drought responses in six arid and semi-arid districts of Kenya (Kajiado, Isiolo, Samburu, Laikipia, Turkana and Marsabit), incorporating feedback from a variety of stakeholders at district and national levels. Chapter 5 provides a checklist for drought-response scenarios; Chapter 6, guidelines for monitoring and evaluating responses to drought; and Chapter 7, a plan for commercial destocking in one of these districts. Chapter 8 summarizes climate change forecasts for Kenya and assesses the need for incorporating climate change adaptation policies into the country’s drought management strategies. Chapter 9 discusses the implications of the findings and makes recommendations. Chapter 10 distils lessons learned. This report is similar to an evaluation of responses to the 2000/2001 drought in Kenya (by Y Aklilu and M Wekesa) and reviews to what extent their recommendations were effectively implemented.

The report’s findings in a nutshell

The number of livestock interventions made increased dramatically between the 2000/2001 and 2008/2009 droughts. The total expenditure was also greater in 2008/2009 (USD4.6 million for 6 districts) than in 2000/20001 (USD4 million in 10 districts). ALRMP and the Kenya Government were the main funders of the efforts. Unfortunately, most livestock-related interventions began very late, in early to mid 2009, well past the optimal timing closer to the onset of the drought, in mid-2008. The ALRMP interventions started earliest, reportedly because it was the only organization with funds readily available through its Drought Contingency mode, when the drought became apparent to all. A total of more than 1.5 million people benefited directly from the interventions made in 2008/2009. The cost per individual reached was Kshs3,362, ranging from Kshs163 for water trucking to Kshs8,652 for emergency destocking. An estimated 15,873 tropical livestock units were purchased as part of emergency off-take. Over 5.7 million animals were reached by health interventions between July 2008 and December 2009. Over 1.5 million people were reached by interventions, 413,802 with traditional livestock interventions (destocking, animal health and feeds).

Practical lessons learned

Lesson 1

The most effective interventions were those that facilitated access to under-utilized grazing and watering resources. Those districts in Kenya with little new access to these natural resources are the most vulnerable.

Lesson 2

So-called ‘commercial de-stocking’ remains the least cost-effective drought intervention in Kenya. Long distances to markets, poor timing of interventions and lack of economies of scale all play important roles in making this kind of de-stocking unviable. But more than anything else, lack of an existing dynamic marketing system virtually precludes a commercial de-stocking operation from being cost-effective.

Lesson 3

‘Livestock-fodder-aid’ comes a close second in terms of poor cost-effectiveness. Shipping substantial quantities of bulky commodities such as hay to remote locations is extremely costly and moreover has had little if any measurable impact.

Lesson 4

Slaughter off-take, preferably carried out on the spot, with the meat distributed rapidly to needy families, is a popular intervention with beneficiaries and can provide substantial benefits. Those that sell a live animal often benefit also from the distribution of its meat. And the availability of this high-protein food can benefit household nutrition while allowing the selling households to maintain a little purchasing power a little longer.

More specific findings

• The number of livestock-related interventions and the funding associated with these both increased considerably over the interventions carried out during the last drought in Kenya, in 2000/2001.

• Once established, risk management systems tend to become static, but effective risk-management systems need to be adaptive and to build in mechanisms for people to ‘learn’.

• Few interventions were made by mid-2008, when the drought was already apparent. Early interventions are preferable as they are more effective. Yet 63 per cent of all interventions, and all destocking programs, were conducted after June 2009, when the drought was at its peak.

• Centrally managed interventions from Nairobi, such as the provision of fodder and the Ministry of Livestock Development-funded market off-take through the Kenya Meat Commission, had little impact and would have been many times more effective if funds had been made available through Drought Management Structures. (Considerable harm was done when publicized sales of stock never materialized, with large numbers of the animals herded to specified collection points suffering horribly and dying for lack of water and fodder.)

• Unmanaged resource-related conflicts among ethnic groups were reported to be a major constraint to an equitable use of the diminishing natural resource base.

• Bringing in water with tankers, maintaining and developing boreholes and destocking by slaughter in the affected areas were generally considered to be the most effective interventions. Most ‘other water’ and animal feeding interventions were considered ineffective.

• Being more effective is not simply a question of spending more money; significant gains can be made by improving the way current resources are spent. (Across all types of interventions, no significant relationship was found between the effectiveness of a given intervention and its cost per individual reached.)

• The problems of many unsuccessful interventions, such as animal feed and health, were due largely to inefficiency of implementation and/or poor timing.

• A third more animals were moved in 2008/2009 than in 2000/2001. As disease killed many of the animals that migrated, animal health interventions should be included in future migration strategies.

• Hay provisioning, which when well done might be an appropriate intervention, was generally too late and too little to have any significant impact on supporting animal herds through the drought.

• Apart from Turkana and Samburu districts, no information on livestock marketing was disseminated or off-take exercises publicized, resulting in late off-takes and a greater expenditure of resources for off-take during the emergency stage than during the alert/alarm stage.

• Bulletins put out by EWS (Early Warning Systems) provide overly generalized information, with no specific livestock focus, making the information inappropriate for livestock interventions. The information also often appears late, is too generic for district-specific interventions, and defines no thresholds for the release of contingency funds.

• A lack of publicly available near-real-time and historic rainfall data hampered the real time analysis of rainfall anomalies. From a timeliness perspective, rainfall data is the most appropriate source of information for early warning, as it allows the longest response time to scale up relief operations. A number of organizational issues in the hands of government could improve this situation.

• Analysis of monthly vegetation greenness anomalies does not appropriately reveal rangeland drought conditions relevant for livestock, as livestock manages to cope with shorter periods of reduced forage availability. A twelve-month running average of NDVI (normalized difference vegetation index) detected historic droughts much more precisely, indicating the usefulness of running average techniques for rangeland early warning purposes.

• Satellite imagery allows near real time to screen opportunities for migration and identify for remedial conflict resolution in areas of high insecurity.

• The reporting on livestock body condition, milk production and productivity proved to be inconsistent across districts, frequently incomplete and with units of measurement unspecified, indicating the need to harmonize the collection of livestock statistics.

Read ILRI’s whole report: An assessment of the response to the 2008–2009 drought in Kenya: A report to the European Union Delegation to the Republic of Kenya, 2010, by Lammert Zwaagstra, Zahra Sharif, Ayago Wambile, Jan de Leeuw, Mohamed Said, Nancy Johnson, Jemimah Njuki, Polly Ericksen and Mario Herrero.

* * *

Read an earlier ILRI News blog on this report: Livestock-based research recommendations for better managing drought in Kenya, 18 Jul 2011.

Three other recent ILRI research reports, published since that above, also assess the effectiveness of past drought interventions in Kenya’s northern drylands and offer tools for better management of the region’s drought cycles.

(1) ILRI research charts ways to better livestock-related drought interventions in Kenya’s drylands. ILRI Policy Brief (this is a distillation of recommendations in the report above), Jul 2011, by Jan de Leeuw, Polly Ericksen, Jane Gitau, Lammert Zwaagstra and Susan MacMillan

(2) The impacts of the Arid Lands Resource Management Project (ALRMPII) on livelihoods and vulnerability in the arid and semi-arid lands of Kenya. ILRI Research Report 25, 2011, edited by Nancy Johnson and Ayago Wambile.

This study assesses the impacts of the Arid Lands Resource Management Project (ALRMPII), a community-based drought management initiative implemented in 28 arid and semi-arid districts in Kenya from 2003 to 2010 to improve the effectiveness of emergency drought response while at the same time reducing vulnerability, empowering local communities, and raising the profile of ASALs in national policies and institutions.

(3) Livestock drought management tool. Final report for a project submitted by ILRI to the FAO Sub-Regional Emergency and Rehabilitation Officer for East and Central Africa, 10 Dec 2010, by Polly Ericksen, Jan de Leeuw and Carlos Quiros.

In August 2010, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) sub-Regional Emergency Office for Eastern and Central Africa contracted ILRI to develop a prototype livestock drought management decision support tool for use by a range of emergency and relief planners and practitioners throughout the region. The tool, which is still conceptual rather than operational, links the concepts of ‘drought cycle management’ with best practice in livestock-related interventions throughout all phases of a drought, from normal through the alert and emergency stages to recovery. The tool uses data to indicate the severity of the drought (hazard) and the ability of livestock to survive the drought (sensitivity). The hazard data has currently been parameterized for Kenya, but can be used in any countries of East and Central Africa. The tool still lacks good-quality data for sensitivity and requires pilot testing in a few local areas before it can be rolled out.