Two Maasai from the Kitengela rangelands near Nairobi—David Nkedianye (left), an ILRI research fellow studying for his PhD, and Ogeli ole Makui (right), a participant in ILRI research—discuss a land-use planning map they have created with ILRI that will help the Maasai community in Kitengela to conserve both their pastoral ways of life and the wildlife that share their rangelands (photo credit: ILRI/Mann).

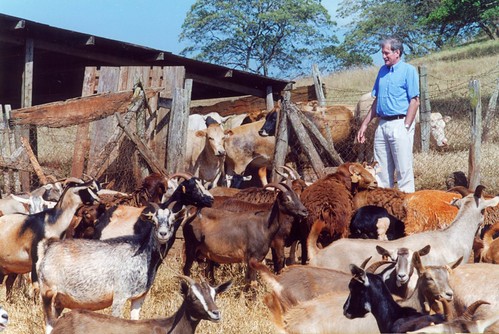

In the beautiful, picturesque and wildlife-rich Kitengela plains just outside of Kenya’s capital, Nairobi, a unique change is taking place among Maasai livestock keepers, who have roamed these plains with their herds of cattle, sheep and goats for generations.

This change is shaping lives as well as livelihoods. James Turere Leparan is a traditional Maasai elder and herder who has watched this change take place in the last few years.

It all began when a group of scientists from the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) began a study in the area in 2003. ‘A group of people came to talk to us about our land’ he says. ‘They said they wanted to help us improve our livestock by helping us deal with the problems we were facing of conflict with wildlife and how best to deal with the division of what once was communal land. They began to meet with us in order to help us change the situation.’ At that time, human-wildlife conflicts between the Maasai people and wild animals from the adjacent Nairobi National Park were common. These conflicts stemmed from the fencing off of what were once communal lands. Such fencing had restricted, and in some cases blocked, animal migratory routes leading to greater conflicts between humans and animals. No less that 50 community meetings were held during the project.

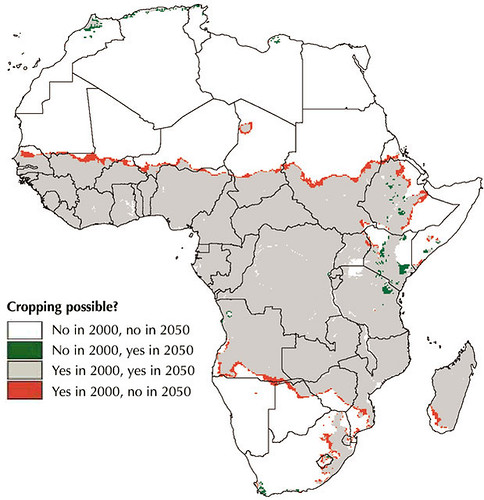

At the time, ILRI planned to map out the Kitengela rangelands to find out how the sub-division of communal lands into private plots and subsequent fencing had affected herders and livestock productivity in the area. The mapping initiated by ILRI and the Kitengela community sought ways the community could best use the land for both domestic and wild animal enterprises.

‘One of the most important considerations we had in the project was to come up with solutions that would not compromise the wildlife migratory routes while also helping to improve Maasai livestock herding,’ says Mohammed Said, a scientist at ILRI and one of the leaders of the project. ‘We explored various innovative ways of helping the Kitengela community best use their land for both livestock and wildlife,’ he adds.

Most of the mapping was started by ILRI’s Mohammed and Shem Chege who are graduates of the faculty of Geo-information and Earth Observation (ITC) of the University of Twente in Netherlands. In partnership with the Africa Wildlife Foundation and the local community, ILRI extended a process of mapping using geographic information systems (GIS) technology to record spatial information about the Kitengela rangelands. Community members were trained in the use of global position satellite (GPS) devises to map the locations of fences, water sources, roads and open pasture land.

‘We soon realized that the local community had a lot of spatial knowledge,’ says Said. ‘They accurately collected spatial data about their land without the use of topographical maps, mostly by using physical features such as rivers. Their data were very accurate.’ ‘The decision to involve the community is one of the key strengths of this project,’ Said added. ‘We trained over 20 community members on how to use GPS equipment and systems to collect information that was then compiled. This built local ownership. The community realized that their contribution was just as important as that of the researchers.’

In 2001 a conservation group called Friends of the Nairobi National Park pioneered a land-leasing scheme that would pay livestock herders three times a year not to fence and develop their land, which would allow wildlife to move easily back and forth from Nairobi National Park within a Kitengela ‘corridor’. This scheme received support from the Africa Wildlife Foundation.

Soon after this, the project members identified the urgent need to develop a land-use ‘master plan’ for Kitengela to ensure that the lease program would succeed. David Nkedianye, a Kitengela Maasai who recently obtained his doctorate through his research at ILRI, said that for the program to succeed, ‘We needed to organize how we used the land. This prompted us to include in our research a project to map the lands in Kitengela that were fenced and unfenced. With this map, we could see where we needed to keep lands open for livestock and wildlife movements.’ This collection of spatial information and participatory land-use planning in Kitengela has produced some unique successes.

Now, four years after the start of this participatory mapping project, conducted with the help of geographic information systems, some 2000 sq km of the Kitengela plains have been mapped. These maps and other outputs of the project have been shared with the local herders and farmers. The local county council of Olkejuado has adopted the projects findings and maps.

The Council will use these to guide future land use in Kitengela’s wildlife-rich rangelands. A scheme to pay the local herders and farmers to keep their land open has been established. Such herders and farmers get US$4 for every acre of unfenced land. More than 30,000 acres of land are now under lease in this scheme and it is expected that this will double by the end of the year. The community is earning about US$120,000 each year from their land conservation efforts.

Other efforts in the Mara, such as those to develop community ‘wildlife conservancies’ have earned the Maasai community more than US$2 million. The availability of distribution maps of different species of animals, including livestock, now enables farmers to conduct their own ground counts of animals in the rangelands without having to use expensive methods such as aerial counts.

Since 2004, the rangeland maps have been updated to identify new and emerging threats that affect livestock keepers and herders. The community of Kitengela is now combining state-of-the-art geospatial information with local knowledge and experiences to better maintain their ecosystem while also benefiting economically from protecting the wildlife that co-exists with them. The greater income gained by James Turere and hundreds of others is bettering the lives of families and meeting their basic needs such as food and education. A major victory of this project has been its ability to influence land policy. Four months ago, the Kenya Government approved the Kitengela land-use map built by the local community, ILRI, the African Wildlife Foundation and other stakeholders.

The experiences and lessons of this project are now being applied elsewhere. One of the partners in the project is piloting a similar model to map land use in the Maasai Mara Game Reserve. A project in Tanzania conducted with ILRI and the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation is encouraging local people to map their own land for better management of their livestock and wildlife resources. Said believes that more farming and herding communities should be trained to use geospatial technologies. He is optimistic that the lessons from this project will have lasting benefits on the region’s livestock sectors as well as on the people of Kitengela.

The findings of the participatory land-use planning project in Kitengela are among many experiences of using geospatial information to support African farmers that were shared during an African Agriculture Geospatial Week that took place at ILRI’s campus in Nairobi last week, 8–13 June 2010.

More information about how geographic information systems are being adopted by the Consultative Group on International Agriculture Research (CGIAR) can be found here. You can also see the proceedings from the conference on Twitter #aagw10.