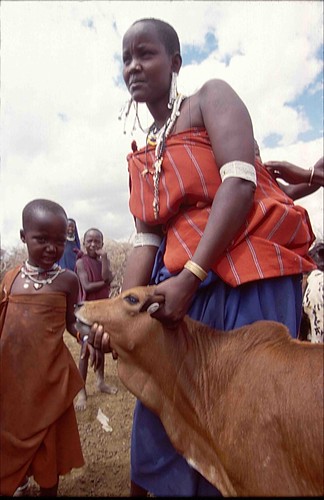

Ramand Ram with goats in his family’s plot in Rajasthan, India. Intensifying mixed crop-and-livestock farming and helping livestock keepers diversify their sources of income can protect livestock livelihoods (photo credit: ILRI/Mann).

Researchers say that poor countries can protect both livestock livelihoods and environments by promoting measures such as sustainably intensifying mixed crop-and-livestock farming, paying livestock keepers for the ecosystem services they provide, helping pastoralists diversify their sources of income and managing the demand for livestock products.

Researchers from the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations and the Animal Production Systems Group at Wageningen University, in the Netherlands, report in a proceedings published last November (2010) that there are ‘significant opportunities in livestock systems for improving environment management while also improving the livelihoods of poor people.’

The publication, titled The Role of Livestock in Developing Communities: Enhancing Multifunctionality, was co-published by the University of the Free State South Africa, the Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation and ILRI. The authors say that even though livestock production is already harming some environments, with such damage likely to increase in some regions in coming years due to an increasing demand from rapidly expanding populations in the developing world, new research-based options for livestock production can help improve both the livelihoods and environments of hundreds of millions of very poor people who raise farm animals or sell or consume their milk, meat and eggs.

The researchers propose shifting the debate on livestock and environment from one that focuses solely on the negative impacts of livestock production to one that embraces the complexity of livestock ‘goods’ and ‘bads’, particularly in developing countries, where livestock serve as a lifeline to many poor people.

The researchers say a good understanding of the environmental impacts of livestock production depends on distinguishing these impacts by region and production system and by addressing environmental problems along with problems of food insecurity and inequity.

The authors, who include ILRI scientists Mario Herrero, Phil Thornton, An Notenbaert, Shirley Tarawali and Delia Grace, recommend making a ‘fundamental shift’ in how demand for livestock products is seen and in adapting production systems to meet this demand. They suggest, for example, that policymakers consider ways of reducing demand for livestock products in (mostly industrialized) countries where (1) people are damaging their health by consuming too much meat, eggs and milk and (2) intensive ‘factory’ farming is damaging the environment.

The scientists also recommend finding ways of improving water management in livestock production. Recent findings show that livestock water use represents 31 per cent of the total water used for agriculture. The authors report that ‘in rangeland systems, water productivity can be improved by better rangeland management, which has the potential to reduce water use in agriculture by 45 per cent by 2050.’ Another promising idea is to begin paying livestock farmers for the rangeland water purification and other ecosystem services they maintain for the good of the wider community.

To reduce greenhouse gases from livestock systems, the authors recommend that efforts be put in place to intensify production systems in developing countries to produce more livestock products per unit of methane gas. ‘We need to provide significant incentives so that the marginal rangeland areas, often rich in biodiversity, can be protected for the benefit of farmers.’ Other options for reducing livestock-associated greenhouse gasses include improving animal diets, controlling animal numbers and shifting the kinds of breeds kept.

Although diseases transmitted between livestock and people also need to be addressed by research, the book notes that the ‘net effects of livestock on human health are positive,’ particularly due to livestock’s role in providing nourishing food for the poor and the contribution livestock herders make to regulating vast rangeland ecosystems, with their wildlife populations, which often helps prevent animals diseases from spilling over to human populations. Better use of disease control methodologies and investments will also help prevent the spread of these diseases.

The authors acknowledge that such changes in the way that livestock production is viewed will require a ‘subtle balancing act’ and commitments by a wide range of players in the scientific, development and policymaking communities. But without a more nuanced understanding of livestock production in the face of hard trade-offs between livestock and the environment, we could jeopardize the livestock livelihoods of many of the world’s ‘bottom billion’.

—

This article is summary of the chapter ‘The Way Forward for Livestock and the Environment’ in the The Role of Livestock in Developing Communities: Enhancing Multifunctionality.

For more information read this related ILRI News article.