Profile of a cow kept by the Rajasthani agro-pastoralists who have inhabited India’s state of Rajasthan (‘land of kings’ or ‘colours’), from the Great Thar Desert in the northwest to the better-watered regions of the southeast, since parts of it formed the great trading and urban Indus Valley (3000-500 BC) and Harappan (1,000 BC) civilizations (photo credit: ILRI/Susan MacMillan).

We know that livestock produce significant amounts of greenhouse gases. Just how much remains somewhat contentious, with the estimated contributions of livestock to global greenhouse gas emissions ranging from 10 to 51%, depending on who is doing the analyses, and how.

A new commentary, published in a special ‘animal feed’ issue of the scientific journal Animal Feed and Technology, examines the main discrepancies between well known and documented studies such as FAO’s Livestock Long Shadow report (FAO 2006) and some more recent estimates. The authors of the commentary advocate for better documentation of assumptions and methodologies for estimating emissions and the need for greater scientific debate, discussion and scrutiny in this area.

The authors of the new article, ‘Livestock and greenhouse gas emissions: The importance of getting the numbers right,’ are a distinguished group of experts from diverse institutions working in this area, including the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO, Rome), Wageningen University and Research Centre (Netherlands), the Food Climate Research Network at the Centre for Environmental Strategy (FCRN, University of Surrey), the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre at the Institute for Environment and Sustainability (JRC, Italy), the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency (PBL, Bilthoven), Aarhus University’s Department of Agroecology and Environment (Denmark), New Zealand’s Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (Wellington), the Institute Nationale de la Recherche Agronomique (France), the Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada group at Lethbridge Research Centre (Alberta) and the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI, Nairobi).

This group of international scientists presents the case of one recent argument as follows.

‘In 2006, the FAO’s Livestock’s Long Shadow report (FAO, 2006), using well documented and rigorous life cycle analyses, estimated that global livestock contributes to 18% of global GHG [greenhouse gas] emissions. According to the study the main contributors to GHG from livestock systems are land use change (carbon dioxide, CO2), enteric fermentation from ruminants (methane, CH4) and manure management (nitrous oxide, N2O).

‘A . . . non-peer reviewed report published by the Worldwatch Institute (Goodland and Anhang 2009) contested these figures and argued that GHG emissions from livestock could be closer to 51% of global GHG emissions. In our view, this report has oversimplified the issue with respect to livestock production. It has emphasised the negative impacts without highlighting the positives and, in doing so, has used a methodological approach which we believe to be flawed.’

Mario Herrero, lead author of the Animal Feed and Technology paper, is a systems analyst and climate change specialist working at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI). Herrero argues that Goodland and Anhang, while claiming in the non-scientifically peer-reviewed World Watch Magazine (which is published by Worldwatch Institute) that livestock generate 51% of total anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions rather than the 18% reported by FAO in 2007, fail to detail the methodologies they used to come up with this new figure, fail to use those methods consistently across different sectors, and fail to follow global guidelines for assessing emissions set by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and Kyoto Protocol.

Furthermore, Hererro says, the World Watch authors’ solution to livestock’s contribution to global warming—’to eat less animal products, or better still, none at all’—could push some 1 billion livestock keepers and consumers living on little more than a dollar a day into even greater poverty (small livestock enterprises are the mainstay of many poor people) and severe malnourishment (milk is among the few high-quality foods readily available to many poor people, with consumption of modest quantities of dairy making the difference between health and illness, especially in children and women of child-bearing ages).

Goodland and Anhang also fail to enlarge on any counterfactuals, such as what a world without domesticated livestock would look like.

Over a billion people make a living from livestock, says ILRI director general Carlos Seré. Most of them are among the poorest of the poor. What, other than livestock keeping, would most African and Indian farming households turn to in order to meet their needs for scarce protein, fertilizer, employment, income, traction, means of saving, and insurance against crop failure?

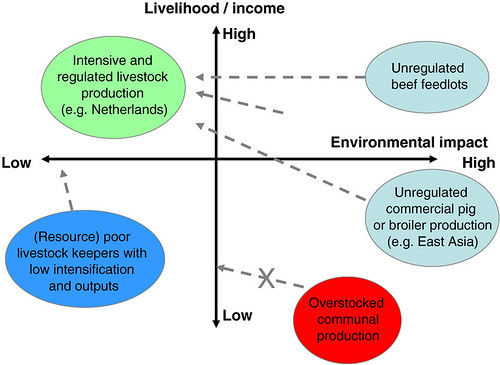

While many of us may find the factory farming of animals in rich countries objectionable on several grounds, Seré says, we must be responsible not to conflate industrial grain-fed livestock systems of rich producers with the family farming and herding practices of hundreds of millions of poor producers, most of whom still maintain their animals not on grain but on pasture grass and other crop wastes not edible by humans.

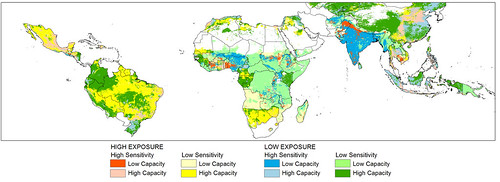

The biggest concern of many experts regarding livestock in developing countries, Seré says, is not their impact on climate change but rather the impact of climate change on livestock production.

The hotter and more extreme tropical environments being predicted threaten not only up to a billion livelihoods based on livestock but also supplies of milk, meat and eggs among hungry communities that need these nourishing foods most. For people living in absolute poverty and chronic hunger, the solution is not to rid the world of livestock, but rather to find ways to farm animals more efficiently and profitably, as well as sustainably.

Tara Garnett, a co-author of the new paper and a research fellow at the Centre for Environmental Strategy at the University of Surrey, in the UK, investigates issues around livestock and greenhouse gas emissions in her highly credible and readable publication Cooking up a Storm: Food, Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Our Changing Climate (2008). Garnett, who also runs the Food Climate Research Network (FCRN), which brings together nearly 2,000 individuals from a broad variety of disciplines to share information on issues relating to food and climate change, agrees with Seré on this.

By 2050, on current projections, Garnett reports, the developing world will still, on average, be eating less than half as much meat as people do in the rich world, and only a third of the milk. There is a long way to go before they catch up with developed world levels.

While there is an increasingly urgent need to reduce demand for meat and dairy products among consumers in developed countries, and also to moderate rapid growth in demand for these foods in emerging, rapidly industrializing, countries, for the world’s poorest people, small-scale livestock enterprises can increase household incomes and improve livelihoods. Greater consumption of meat and dairy products—in addition to a more diverse range of plant-based foods—can play a critical role in combatting malnutrition and enhancing nutritional status.’

Herrero and Garnett and their other co-authors conclude that ‘Livestock undoubtedly need to be a priority focus of attention as the global community seeks to address the challenge of climate change. The magnitude of the discrepancy between the Goodland and Anhang paper (2009) and widely recognized estimates of GHG from livestock (FAO, 2006), illustrates the need to provide the climate change community and policy makers with accurate emissions estimates and information about the link between agriculture and climate.

‘Improving the global estimates of GHG attributed to livestock systems is of paramount importance. This is not only because we need to define the magnitude of the impact of livestock on climate change, but also because we need to understand their contribution relative to other sources. Such information will enable effective mitigation options to be designed to reduce emissions and improve the sustainability of the livestock sector while continuing to provide livelihoods and food for a wide range of people, especially the poor. We need to understand where livestock can help and where they hinder the goals of resilient global ecosystems and a sustainable, equitable future for future generations.

‘We believe these efforts need to be part of an ongoing process, but one that is to be conducted through transparent, well established methodologies, rigorous science and open scientific debate. Only in this way will we be able to advance the debate on livestock and climate change and inform policy, climate change negotiations and public opinion more accurately.’

Read the whole post-print paper by Mario Herrero, P Gerber, T Vellinga, T Garnett, A Leip, C Opio, HJ Westhoek, PK Thornton, J Olesen, N Hutchings, H Montgomery, J-F Soussana, H Steinfeld and TA McAllister: Livestock and greenhouse gas emissions: The importance of getting the numbers right, a special issue on ‘Greenhouse Gases in Animal Agriculture—Finding a Balance between Food and Emissions’ published this month in 2011 in Animal Feed Science and Technology 166–167: 779–782 (doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2011.04.083).

Read the Goodland and Anhang article in World Watch Magazine: Livestock and Climate Change: What if the key actors in climate change are…cows, pigs, and chickens? November/December 2009.