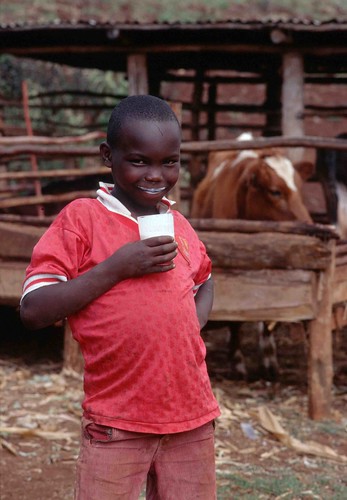

Kenya farm boy drinking milk (photo credit: ILRI/Dave Elsworth).

The science journal Animal Frontiers this month (Jan 2013) focuses on the links between livestock production and food security.

Maggie Gill edited the issue. Gill is an animal nutritionist by training who has spent years as a senior member of research institutions in the the UK (Natural Resources Institute, Natural Resources International, Macaulay Land Use Research Institute, Scottish Government) and presently divides her time between work for the UK Department for International Development and the University of Aberdeen while also serving on the CGIAR’s Independent Science and Partnership Council. She is a former board member of the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI).

In her introductory editorial to this issue, which focuses on livelihoods for poor owners and food for rich consumers, Gill reminds readers of the vast differences in livestock systems between the world’s poor and rich people and nations.

‘The relationship between livestock and food security is often portrayed by the media in emotional terms such as “Go vegetarian to save the planet”. Yet the relationship is not so simple. There are positive impacts of livestock on “the planet,” not the least in terms of the economy, with trade in live animals and animal products contributing 40% of the global value of agricultural output (FAO, 2009), but also in terms of the 1 billion poor people in Africa and Asia who depend on livestock for their livelihoods. The challenge is that there are also negative impacts of livestock, and they tend to be good headline grabbers!

‘I was pleased, therefore, to be invited to serve as guest editor of this issue of Animal Frontiers . . . [and] to have the opportunity to include papers about some of the lesser publicized facts about livestock and food security. . . . [A second issue on this topic will be published in Jul 2013.]

‘This issue takes a high-level perspective, exploring the relationship between people and animals (including fish) in developing countries, through trade and particularly in terms of nutrition. It then looks ahead to the challenge of climate change and considers how one traditional system (pastoralism) has evolved to cope with environmental instability. It ends with a paper on breeding strategies as an illustration of how scientific advances can help the livestock sector to make the best use of resources in a dynamic world. . . .’

One of the seven papers featured in this issue is by Jimmy Smith, ILRI director general, and his ILRI colleagues. The article focuses mainly on the impacts and implications of livestock on food and nutrition security in poor countries, which go well beyond being a source of milk, meat, and eggs.

‘The paper by Smith et al. (2013)’, Gill says, ‘highlights, for example, the indirect benefits of livestock to the food security of poor livestock owners through income from the sale of their livestock products, enabling the purchase of (cheaper) staple foods and thus improving the nutritional status of members of the household, albeit not in the way many researchers expect! . . .’

Below are a few of the facts noted in Smith’s paper, ‘Beyond meat, milk and eggs: Role of livestock in food and nutrition security’.

Farm animals both increase (smallholder systems) and decrease (industrial systems) food supplies

‘Livestock contribute to food supply by converting low-value materials, inedible or unpalatable for people, into milk, meat, and eggs; livestock also decrease food supply by competing with people for food, especially grains fed to pigs and poultry. Currently, livestock supply 13% of energy to the world’s diet but consume one-half the world’s production of grains to do so.’

Livestock directly enhance the nutrition security of the poor

‘However, livestock directly contribute to nutrition security. Milk, meat, and eggs, the “animal-source foods,” though expensive sources of energy, are one of the best sources of high quality protein and micronutrients that are essential for normal development and good health. But poor people tend to sell rather than consume the animal-source foods that they produce.’

Livestock enhance food security mostly indirectly

‘The contribution of livestock to food, distinguished from nutrition security among the poor, is mostly indirect: sales of animals or produce, demand for which is rapidly growing, can provide cash for the purchase of staple foods, and provision of manure, draft power, and income for purchase of farm inputs can boost sustainable crop production in mixed crop-livestock systems.’

Smallholder livestock production and marketing can be ‘transformational’ for the world’s poor

‘Livestock have the potential to be transformative: by enhancing food and nutrition security, and providing income to pay for education and other needs, livestock can enable poor children to develop into healthy, well-educated, productive adults.’

The complex trade-offs inherent in livestock systems must be managed to increase the benefits and reduce the costs

‘The challenge is how to manage complex trade-offs to enable livestock’s positive impacts to be realized while minimizing and mitigating negative ones, including threats to the health of people and the environment.’

Read the whole illustrated article at Animal Frontiers: Beyond milk, meat, and eggs: Role of livestock in food and nutrition security, by Jimmy Smith, Keith Sones, Delia Grace, Susan MacMillan, Shirley Tarawali and Mario Herrero, Jan 2013, Vol. 3, No. 1, p 6–13, doi: 10.2527/af.2013-0002

The whole issue is available at Animal Frontiers: The contribution of animal production to global food security: Part 1: Livelihoods for poor owners and food for rich consumers, Jan 2013, which you can read about on the ILRI Clippings Blog today: Animal production and global food security: Livelihoods for poor owners and food for rich consumers, 8 Jan 2012.