A report on the economic as well as health risks of keeping free-range pigs in western Kenya has been published by scientists in the animal health laboratories at ILRI’s Nairobi, Kenya, campus; here, two of the authors, lead author Lian Thomas (left) and principal investigator Eric Fèvre (right), inspect a household pig in their project site, in Busia, in western Kenya (photo credit: ILRI/Charlie Pye-Smith).

Like your livestock products to come from free-range systems? Consider that a healthy alternative to the factory farming of livestock? Consider the lowly pig, and what serious pathogens it can pick up, and transmit to other animals and people, in the course of its daily outdoor scavenging for food. Consider also the scavenging pig’s coprophagic habits (consumption of faeces) and you may change your mind.

A recent study has brought those habits to light. The study was conducted in an area surrounding Busia town, in western Kenya (Busia lies near Kenya’s western border with Uganda; Lake Victoria lies to the south). The study was conducted by scientists at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) and the University of Edinburgh to better understand the transmission of several pathogenic organisms. This is the first study to investigate the ecology of domestic pigs kept under a free-range system, utilizing GPS technology.

Most people in Busia farm for a living, raising livestock and growing maize and other staple food crops on small plots of land (the average farm size here is 0.5 ha). More than 66,000 pigs are estimated to be kept within a 45-km radius of Busia town.

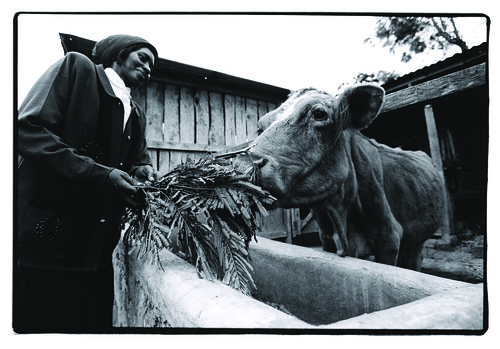

ILRI’s Lian Thomas with a household pig in western Kenya (photo credit: ILRI/Charlie Pye-Smith).

A GPS collar was put on 10 pigs, each nearly 7 months old, that were recruited for this study. A handheld GPS unit was used to obtain the coordinates of the homesteads to which the selected pigs belonged; the perimeters of the homesteads and their main features, including human dwellings, cooking points, rubbish disposal areas and latrines, were all mapped. The pig collars recorded the coordinates of the pigs every 3 minutes during the course of one week.

All the 10 pigs were kept under free-range conditions, but also regularly fed supplementary crop and (mostly raw) household waste. All the pigs recruited were found to be infected with at least one parasite, with most in addition also having gastrointestinal parasites, and all carried ticks and head lice.

The pigs, which scavenge both day and night, were found to spend almost half their time outside the homestead, travelling an average of more than 4 km in a 12-hour period (both day and night), with a mean home range of 10,343 square meters. One implication of this is that a community approach to better controlling infectious diseases in pigs will be better suited to this farming area than an approach that targets individual household families.

Three of the ten pigs were found to be infected with Taenia solium, a pig tapeworm whose larva when ingested by humans in undercooked pork causes the human disease known as cysticercosis, which can cause seizures, epilepsy and other disorders, and can be fatal if not treated. T solium infection in pigs is acquired by their ingestion of infective eggs in human faecal material, which is commonly found in the pigs environments in rural parts of Africa as well as Mexico, South America and other developing regions.

This study found no correlation between the time a pig spent interacting with a latrine at its homestead and the T solium status of the pig. The paper’s authors conclude that ‘the presence or absence of a latrine in an individual homestead is of less relevance to parasite transmission than overall provision of sanitation for the wider community in which the pig roams’. With a quarter of the homesteads in the study area having no access to a latrine, forcing people to engage in open defecation, and with less than a third of the latrines properly enclosed, there are plenty of opportunties for scavenging pigs to find human faeces.

A typical household scavenging pig and pit latrine in the project site in Busia, Kenya (photo credit: ILRI/Charlie Pye-Smith).

Improved husbandry practices, including the use of effective anthelmintics at correct dosages, would enhance pig health and production in this study area.

One of the interesting findings of the study is that all this pig roaming is likely to be helping to reduce the weight of the pigs at slaughter. Mean live weights at the abattoir in the Busia area are 30 kg, giving a dressed weight of only 22.5 kg and earning the farmer only KShs.2000–2500 (USD24–29) per animal.

Encouraging the confinement of pigs is likely to improve feed conversion and weight gain, by both reducing un-necessary energy expenditure as well as limiting parasite burden through environmental exposure.

‘Confinement of pigs would also reduce the risk of contact with other domestic or wild pigs: pig to pig contact is a driver of African swine fever (ASF) virus transmission. ASF regularly causes outbreaks in this region . . . . Confining pigs within correctly constructed pig stys would also reduce the chances of contact between pigs and tsetse flies.’ That matters because this western part of Kenya is a trypanosomiasis-endemic area and pigs are known to be important hosts and reservoirs of protozoan parasites that cause both human sleeping sickness, which eventually is fatal for all those who don’t get treatment, and African animal trypanosomiasis, a wasting disease of cattle and other livestock that is arguably Africa’s most devastating livestock disease.

In addition, both trichinellosis (caused by eating undercooked pork infected by the larva of a roundworm) and toxoplasmosis (caused by a protozoan pathogen through ingestion of cat faeces or undercooked meat) are ‘very real threats to these free-ranging pigs, with access to kitchen waste, in particular meat products, being a risk factor for infection. Such swill is also implicated in ASF transmission’.

While confining pigs would clearly be advantageous for all of these reasons, the practice of free range will likely be hard to displace, not least because this low-input system is within the scarce means of this region’s severely resource-poor farmers. Local extension services, therefore, will be wise to use carrots as well as sticks to persuade farmers to start ‘zero-scavenging’ pig husbandry, Fortunately, as this study indicates, they can do this by demonstrating to farmers the economic as well as health benefits they will accrue by penning, and pen-feeding, their free-ranging pigs.

Scavenging pigs in Busia, western Kenya (photo credit: ILRI/Charlie Pye-Smith).

Project funders

This research was supported by the Wellcome Trust, BBSRC (Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council) and MRC (Medical Research Council), all of Great Britain. It is also an output of a component of the CGIAR Research Program on Agriculture for Nutrition and Health investigating Agriculture-Associated Diseases.

Read the whole paper

The spatial ecology of free-ranging domestic pigs (Sus scrofa) in western Kenya, by Lian Thomas, William de Glanville, Elizabeth Cook and Eric Fèvre, BMC Veterinary Research 2013, 9:46. doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-9-46

Article URL

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1746-6148/9/47 The publication date of this article is 7 Mar 2013; you will find here a provisional PDF; fully formatted PDF and full text (HTML) versions of the paper will be available soon.

About the project

Begun in 2009 and funded by the Wellcome Trust, with other support from ILRI, this project has studied neglected zoonotic diseases and their epidemiology to raise levels of health in poor rural communities. The project, People, Animals and their Zoonoses (PAZ), is based in western Kenya’s Busia District and is led by Eric Fèvre, who is on joint appointment at ILRI and the University of Edinburgh. More information can be found at the University of Edinburgh’s Zoonotic and Emerging Diseases webpage or on ILRI’s PAZ project blog site.

The May 2010 issue of the Veterinary Record gives an excellent account of this ambitious human-animal health project: One medicine: Focusing on neglected zoonoses.

Related stories on ILRI’s AgHealth, Clippings and News blogs

Tracking of free range domestic pigs in western Kenya provides new insights into dynamics of disease transmission, 22 Mar 2013.

Aliens in human brains: Pig tapeworm is an alarming, and important, human disease worldwide, 23 May 2012.

Forestalling the next plague: Building a first picture of all diseases afflicting people and animals in Africa, 11 Apr 2011. This blog describes an episode about this project broadcast by the Australian science television program ‘Catalyst’; you can download the episode here: ABC website (click open the year ‘2011’ and scroll down to click on the link to ‘Episode 4’; the story starts at 00.18.25).

Edinburgh-Wellcome-ILRI project addresses neglected zoonotic diseases in western Kenya, 28 Jul 2010.