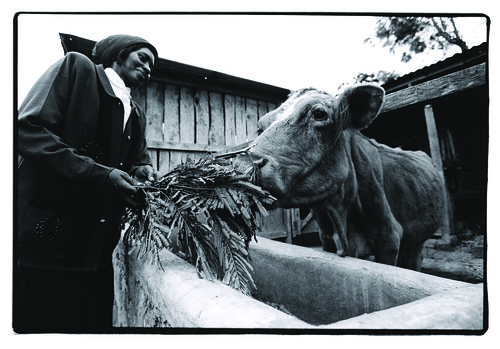

An ILRI-Wellcome project is investigating the disease pathogens circulating in both people and animals in the communities outside the border town of Busia, Kenya, where smallholders mix crop growing with livestock raising (photo credit: ILRI/Pye-Smith).

A project funded by the Wellcome Trust on zoonotic diseases was broadcast last week on an Australian television program called ‘Catalyst’. The show ran on Thursday, 10 March 2011, at 20:00 Australian time. The research described in the program is supported by the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), where the project’s principal investigator, Eric Fevre, is hosted.

The television program interviews Fevre and his colleagues Lian Doble, a veterinarian managing laboratory work in western Kenya, and Appolinaire Djikeng, technology manager of a Biosciences eastern and central Africa (BecA) Hub, located on ILRI’s Nairobi, Kenya, campus.

Fevre and Doble and their team are investigating what disease pathogens of both people and animals are circulating near the border town of Busia, a very poor, densely populated area whose communities mix crop growing with livestock raising on small plots of land. Research such as this that is looking at both human and animal diseases is rare but urgently needed because the close relations of people and farm animals in many poor regions, as well as the existence of monkeys and other wildlife nearby, is a ‘recipe for diseases’ jumping from animals to people. If we’re going to manage to forestall another zoonotic plague such as bird flu or HIV/AIDS, we’re going to have to conduct more of such ‘one health’ investigations that look at exactly what diseases are being transmitted between animals and people. The research project in western Kenya is part of a larger study being conducted by the BecA Hub to look at diseases of animals and people across eastern Africa. The BecA Hub team is using genomics and meta-genomics, and ‘4 million bucks of computing power,’ to build a picture of the complex relations of disease pathogens circulating in the region.

Eric Fevre, who leads the ILRI-Wellcome project investigating the disease pathogens circulating in both people and animals in Busia, points out a pit latrine frequented by pigs as well as people, where disease transmission between the two species is most likely to occur (photo credit: ILRI/Pye-Smith).

A transcript of the Australian television program on this research follows.

NARRATION

Africa, the cradle of humanity and renowned for its wildlife. It could also be the origin of the next global pandemic. It’s long been known that people and animals living close together—well, that’s a recipe for disease. But exactly which diseases? And if new diseases are creeping into the system? Well, that’s something they’re trying to find out here in western Kenya. They’re called zoonotic diseases: infections that can jump from animals to people.

Eric Fevre

There are lots of zoonotic infections. In fact, about 60 per cent of all human diseases are of zoonotic origin.

NARRATION

So this team headed by Eric Fevre is taking a much closer look at the health of people and livestock in a densely populated region of western Kenya.

Eric Fevre

It seems to be obvious that zoonotic infections will occur more in people who keep livestock than in those who don’t. Whether that’s the case has never been formally established.

Lian Doble

If you look around here you don’t see the cattle in a field, in a fenced field or in a barn away from the people. Cattle are tethered within the compound that everybody’s working in, the chickens are loose around, going in and out of the houses. It’s a much more integrated system than anything we really see at home.

NARRATION

The kinds of problems that this environment creates are readily apparent.

Eric Fevre

We’re in a mixed crop-livestock production system where people are keeping a few animals. And as you can see behind me here, it’s the rainy season and people have recently planted their new crops. And this is an area of interaction between the croplands and the animals. And you can see behind over there behind those fields is some forest. And there might be a watercourse flowing through that forest, for example, where the animals are going to water. And that’s where the exciting things happen from a disease transmission point of view.

NARRATION

Part of the team focus on human health, taking a range of samples from people in the village as well as a detailed account of their medical history and current living situation. Meanwhile, others in the team have a look at the livestock.

Lian Doble

What we do know is that there are a large number of diseases that circulate between animals and humans. The problem is that a lot of these diseases cause signs which are very similar to other human diseases like malaria and human tuberculosis. What isn’t known is actually how many of the diseases that are mainly diagnosed as malaria actually are another disease caused by the pathogens found in cattle. So we’re just trying to find out what diseases she has and what are shared with the people that she lives with.

Paul Willis

And does she look healthy?

Lian Doble

She’s feisty and she’s quite healthy so we’ll see what she might have been carrying. And we can tell you later in the lab.

NARRATION

Samples are taken back to field laboratories in the town of Busia on the Ugandan border.

The ILRI-Wellcome Trust animal-human laboratory in Busia, Kenya (photo credit: ILRI/Pye-Smith).

Eric Fevre

In this place we’ve got a human and an animal lab next door where we process the material that comes in from the field. One of the things that we really need to do is look at fresh material. Because once the samples get a bit old, the parasites become a bit difficult to identify. And the second important thing is that we of course feed back to the participants of our study. So results that we get in the lab here are used directly by the clinicians working in the field to decide what treatments they should be giving people. So that’s one of the direct ways that our research project feeds back into the community.

NARRATION

This detailed look at the community health of a whole region is showing many expected results, and a few surprises.

Eric Fevre

One of the diseases that we’re testing for is brucellosis. And looking at the official reports there isn’t any brucellosis in this region. But we have detected brucellosis both in animals and in people and so already that’s what’s telling us that there are things circulating here that official records don’t pick up.

NARRATION

There seems to be a lot of malaria around, but Eric’s team are finding that many cases are masking something much more sinister.

Eric Fevre

Often it won’t be malaria. It will be something else. And there are a multitude of different pathogens that cause fever of the type that malaria also causes. And that’s a real problem. Because somebody with a low income might need to, say, sell one of their animals to then go to the clinic, get a diagnosis, buy some anti-malarial drugs. They don’t work because the person actually has sleeping sickness. So they go back to a different clinic. Or to a traditional healer. They get drugs that don’t work for the infection that they have. And so on and so on, five, six, seven times, travelling maybe ten kilometres each time. That’s a huge economic burden on them. And then finally they get properly diagnosed when they’re in the late stage of their infection. And it would have been much easier to treat them if they’d have been caught earlier on.

NARRATION

It’s a very complex picture that is emerging, one that could be simplified by some basic technology.

Lian Doble

Thirty per cent of our participants don’t have access to a latrine. You can imagine what that means. And that’s something that could be very actually quite easily sorted out with some education and some money and would sort out all sorts of other diarrhoeal diseases, which are one of the huge killers of young children in Africa.

One of the ultra-modern laboratories at the Biosciences eastern and central Africa (BecA) Hub ‘platform’ hosted and managed by ILRI in Nairobi, Kenya (photo credit: ILRI/White).

NARRATION

Back in Nairobi another team is taking a different look at the spread of diseases across east Africa.

NARRATION

Appolinaire Djikeng heads up a team collecting samples of animals and people from a wide swath across Kenya.

Appolinaire Djikeng

So essentially at the moment we are trying to cover the east African region. But of course we would like to once we establish our processes and data management skills and data analysis skills we like to expand this to other parts of Africa.

NARRATION

The first step in the labs is to figure out exactly what spread of diseases are present in their samples.

Appolinaire Djikeng

You are able to go in there, look at the, the complex composition of the viruses, at the pathogens or at the small organisms that exist in them in doing it that way you are able to come up with a catalogue of potential organisms that exist in there.

NARRATION

And this analysis goes deep into the DNA of the viruses and pathogens that are found, tracking minute changes in their genetic make-up that allows Appolinaire’s team to follow the spread of individual strains of a disease.

Appolinaire Djikeng

We have a reasonably good bioinformatic infrastructure here for storing that data and extracting them, looking at specific parameters from that particular data base. With so many samples from such a wide geographical area and with so much information for each individual sample these guys are dealing with a lot of data and so they brought in four million bucks worth of computing grunt. With so many samples from such a wide geographic area and with so much information for each individual sample these guys are dealing with a lot of data. So they brought in four million bucks worth of computing grunt.

NARRATION

There are several teams looking at zoonotic diseases in Kenya, but the impact of their work is global.

Appolinaire Djikeng

The threat of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases are no longer restricted to countries like central Africa or sub-Saharan Africa So I think now we have to put this work in the context of the global effort across the world. Trying to make sure that even remote parts of the area do have resources and capabilities to begin to do good and accurate diagnostics of what could be emerging.

Eric Fevre

We actually use the data that we gather to, to try and understand how these things are being transmitted, how the fact that your animal has this disease impacts on your risk at a population scale. And, and use that to then try and understand the, the process of transmission of these diseases.

Lian Doble

The next big disease problem is very likely to be a zoonotic disease so doing this sort of work and then leaving it isn’t an option. It needs to be ongoing and, and build. This is the start of something and we’ll build on it from here.

Download this Catalyst show from Australia’s ABC website (select ‘Zoonosis’ 10/3/2011).

And check out a blog by Paul Willis about the adventures of filming in Kenya’s border town of Busia: Coming to an end, 7 March 2011.

Here’s some of what Paul Willis has to say in his blog about this film project:

‘Busia is a hard place; a border crossing town riddled with grinding poverty and hard living. The main street, the only sealed road through town, is frequently clogged with a seemingly endless string of trucks waiting to cross the border into Uganda. Because Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi are all landlocked nations, every drop of fuel and most freight coming into the country has to be trucked in from Mombasa and most of that comes through Busia. . . . This area of Kenya has some of the most intensively farmed land in East Africa. The whole landscape is divided into small plots with clusters of mud and thatch huts scattered among them. Here people live cheek-by-jowl with their crops and animals. It’s a recipe for diseases to jump from animals to people. Add strips of forested vegetation inhabited by a variety of monkeys and other native mammals and the chances of new diseases leaping into the human population goes up dramatically. We’re here to report on the work of a dedicated group trying to get a handle on exactly what diseases are in this chaotic system. It’s hard work, in one of the hotter areas of Kenya, and the study is spread over a huge area. . . .’