The developing world’s supplies of wheat, livestock, fish, roots, tubers, and bananas, along with the nutrition of its poorer communities and the food policies of its governments, should be enhanced in the coming years by new funding approved by the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), the world’s largest international agriculture research coalition.

The CGIAR has approved six new programs, totalling some USD957 million, aimed at improving food security and the sustainable management of the water, soils and biodiversity that underpin agriculture in the world’s poorest countries. The newly created CGIAR Fund is expected to provide USD477.5 million, with the balance of the support needed likely to come from bilateral donors and other sources.

The six programs focus on sustainably increasing production of wheat, meat, milk, fish, roots, tubers and bananas; improving nutrition and food safety; and identifying the policies and institutions necessary for smallholder producers in rural communities, particularly women, to access markets.

The programs are part of the CGIAR’s bold effort to reduce world hunger and poverty while decreasing the environmental footprint of agriculture. They will target regions of the world where recurrent food crises—combined with the global financial meltdown, volatile energy prices, natural resource depletion, and climate change—undercut and threaten the livelihoods of millions of poor people.

‘More and better investment in agriculture is key to lifting the 75 per cent of poor people who live in rural areas out of poverty,’ said Inger Andersen, CGIAR Fund Council chair and World Bank vice-president for sustainable development. ‘Each of these CGIAR research programs addresses issues that are fundamental to the well-being of poor farmers and consumers in developing countries. Supporting such innovations is key to feeding the nearly one billion people who go to bed hungry every night.’ CGIAR Fund members include developing and industrialized country governments, foundations and international and regional organizations.

Each of the research programs, proposed by the Montpellier-based CGIAR Consortium of International Agricultural Research Centers, is working on a global scale by combining the efforts and expertise of multiple members of the CGIAR Consortium and involving some 300–600 partners from national agricultural research systems; advanced research institutes; non-governmental, civil society and farmer organizations; and the private sector. By working in partnership on such a large scale, the CGIAR-plus=partners effort is unprecedented in size, scope of the partnerships and expected impact.

The six new programs, each implemented by a lead centre from the CGIAR Consortium, join five other research endeavours approved by the CGIAR in the past nine months (on rice, climate change, forests, drylands, and maize) as part of the CGIAR’s global focus on reducing poverty, improving food security and nutrition and sustainably managing natural resources. Each of the six programs described below was approved with an initial three-year budget.

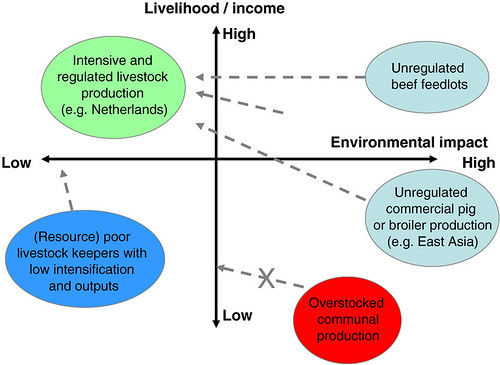

Meat, Milk and Fish (USD119.7m) will increase the productivity and sustainability of small-scale livestock and fish systems to make meat, milk and fish more profitable for poor producers and more available and affordable for poor consumers. Some 600 million rural poor keep livestock while fish—increasingly derived from aquaculture—provide more than 50 per cent of animal protein for 400 million poor people in Africa and South Asia. This program will be led by the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), based in Africa.

Agriculture for Improved Nutrition and Health (USD191.4m) is designed to leverage agriculture improvements to deal with problems related to health and nutrition. It is based on the premise that agricultural practices, interventions and policies can be better aligned and redesigned to maximize health and nutrition benefits and reduce health risks. The program will address the stubborn problems of under-nutrition and ill-health that affect millions of poor people in developing countries. Focus areas include improving the nutritional quality and safety of foods in poor countries, developing biofortified foods and generating knowledge and techniques for controlling animal, food and water-borne diseases. This program will be led by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), based in the USA, with the health aspects led by ILRI.

Wheat (USD113.6m) will create a global alliance for improving productivity and profitability of wheat in the developing world, where demand is projected to increase by 60 per cent by 2050 even as climate change could diminish production by 20 to 30 per cent. Accounting for a fifth of humanity’s food, wheat is second only to rice as a source of calories for developing-country consumers and is the number one source of protein.

Aquatic Agriculture Systems (USD59.4m) will identify gender-equitable options to improve the lives of 50 million poor and vulnerable people who live in coastal zones and along river floodplains by 2022. More than 700 million people depend on aquatic agricultural systems and some 250 million live on less than USD1.25 per day. The program will explore the interplay between farming, fishing, aquaculture, livestock and forestry with efforts focused on linking farmers to markets for their agricultural commodities.

Policies, Institutions and Markets (USD265.6m) will identify the policies and institutions necessary for smallholder producers in rural communities, particularly women, to increase their income through improved access to and use of markets. Insufficient attention to agricultural markets and the policies and institutions that support them remains a major impediment to alleviating poverty in the developing world, where in most areas farming is the principal source of income. This initiative seeks to produce a body of new knowledge that can be used by decision-makers to shape effective policies and institutions that can reduce poverty and promote sustainable rural development.

Roots, Tubers and Bananas (USD207.3m) is designed to improve the yields of farmers in the developing world who lack high-quality seed and the tools to deal with plant disease, plant pests and environmental challenges. Over 200 million poor farmers in developing countries are dependent on locally grown roots, tubers and bananas for food security and income, which can provide an important hedge against food price shocks. Yet yield potentials are reduced by half due to poor quality seed, limited genetic diversity, plant pests and disease and environmental challenges.

‘These programs mark a new approach to collaborative research for development,’ said Carlos Perez del Castillo, CGIAR Consortium Board Chair. ‘They bring together the broadest possible range of organizations to ensure that research leads to development and real action that improves people’s lives.’

Note: The Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) is a global partnership that unites organizations engaged in research for sustainable development with the funders of this work. The funders include developing- and industrialized-country governments, foundations and international and regional organizations. The work they support is carried out by 15 members of a Consortium of International Agricultural Research Centers, in close collaboration with hundreds of partner organizations, including national and regional research institutes, civil society organizations, academia and the private sector.