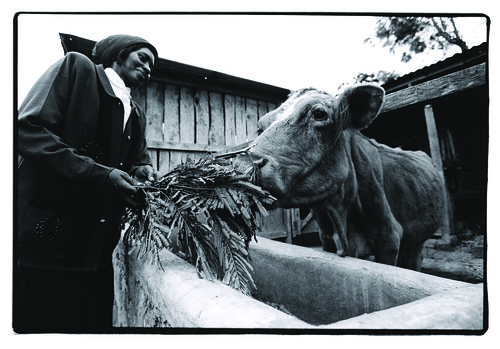

D’ « anciennes » espèces bovines d’Afrique de l’Ouest, résistantes aux maladies, figurent parmi les races qui risquent de disparaître parce que le bétail importé est en train de supplanter un précieux cheptel indigène.

Une action urgente est indispensable pour arrêter la perte rapide et alarmante de la diversité génétique du bétail africain qui apporte nourriture et revenus à 70 % des Africains ruraux et constitue un véritable trésor d’animaux résistants à la sécheresse et aux maladies. C’est ce que dit une analyse présentée aujourd’hui à une importante réunion de scientifiques africains et d’experts du développement.

Les experts de l’Institut international de recherche sur l’élevage (ILRI) ont expliqué aux chercheurs réunis pour la cinquième Semaine africaine des sciences agricoles (www.faraweek.org), accueillie par le Forum pour la recherche agricole en Afrique (FARA), que des investissements sont indispensables aujourd’hui même pour intensifier, en particulier en Afrique de l’Ouest, les efforts d’identification et de préservation des caractères uniques de la riche variété de bétail bovin, ovin, caprin, et porcin, qui s’est développée au long de plusieurs millénaires sur le continent et qui est aujourd’hui menacée. Ces experts expliquent que la perte de la diversité du bétail en Afrique fait partie de « l’effondrement » mondiale du cheptel. Selon l’Organisation des Nations Unies pour l’alimentation et l’agriculture, près de 20 % des 7 616 races de bétail existant dans le monde sont aujourd’hui considérées comme à risque.

« L’élevage africain est un des plus robustes au monde, et pourtant nous assistons aujourd’hui à une dilution, si pas une perte totale, de la diversité génétique de nombreuses races, » dit Abdou Fall, chef du projet diversité animale de l’ILRI pour l’Afrique de l’Ouest. « Mais aujourd’hui, nous avons les outils nécessaires pour identifier les caractéres de grande valeur du bétail africain indigène, une information qui peut être cruciale pour maintenir, voire augmenter la productivité de l’exploitation agricole africaine. »

M. Fall décrit les différentes menaces qui pèsent sur la viabilité à long terme de la production de bétail en Afrique. Ces menaces comprennent une dégradation du paysage et le croissement avec des races « exotiques » importées d’Europe, d’Asie et d’Amérique.

Par exemple, on assiste à un croisement sur une très large échelle de races des zones sahéliennes d’Afrique de l’Ouest et susceptibles aux maladies avec des races adaptées aux régions subhumides, comme le sud du Mali, et qui ont une résistance naturelle à la trypanosomiase.

La trypanosomiase tue entre trois et sept millions de tètes de bétail chaque année et son coût pour les exploitants agricoles se chiffre en milliards de dollars, lorsqu’on prend en compte, par exemple, les pertes de production de lait et de viande, et les coûts de médicaments et prophylactiques nécessaires au traitement ou à la prévention des maladies. Bien que le croisement puisse offrir des avantages à court terme, comme une amélioration de la production de viande et de lait ou une plus grande puissance de trait, il peut également faire disparaître des caractères très précieux qui sont le résultat de milliers d’années de sélection naturelle.

Les experts de l’ILRI déploient à l’heure actuelle des efforts importants en faveur d’une campagne visant à maîtriser le développement d’une résistance aux médicaments chez les parasites qui provoquent la trypanosomiase. Mais ils reconnaissent aussi que des races dotées d’une résistance naturelle à cette maladie offre une meilleure solution à long terme.

Ces races comprennent les bovins sans bosse et à courtes cornes de l’Afrique de l’Ouest et du Centre, qui ont vécu dans cette région avec ces parasites pendant des millions d’années et ont ainsi acquis une résistance naturelle à de nombreuses maladies, y compris la trypanosomiase, propagée par la mouche tsétsé, et les maladies transmises par les tiques. De plus, ces animaux robustes sont capables de résister à des climats rudes. Mais les races à courtes cornes et à longues cornes ont un désavantage : elles ne sont pas aussi productives que les races européennes. Malgré ce désavantage, la disparition de ces races aurait des conséquences graves pour la productivité future du bétail africain.

« Nous avons observé que les races indigènes sans bosse et à courtes cornes d’Afrique de l’Ouest et du Centre font l’objet d’un abatage aveugle et d’un manque d’attention aux bonne pratique d’élevage, et risquent ainsi de disparaître,» explique Fall. « Il faut qu’au minimum nous préservions ces races soit dans le contexte de l’exploitation, soit dans des banques de gènes : leurs caractéristiques génétiques pourraient en effet s’avérer décisives dans la lutte contre le trypanosomiase, et leur robustesse pourrait être un atout essentiel pour des exploitants agricoles qui auront à s’adapter au changement climatique. »

Le Kuri aux grandes cornes bulbeuses du Sud Tchad et du Nord-est du Nigéria fait partie des bovins africains à risques. Non seulement il ne se laisse pas déranger par les piqûres d’insecte mais il est également un excellent nageur, vu qu’il s’est développé dans la région du lac Tchad, et est idéalement adapté aux conditions humides dans des climats très chauds.

Les actions de l’ILRI en faveur de la préservation du bétail africain indigène s’inscrivent dans un effort plus large visant à améliorer la productivité de l’exploitation agricole africaine au travers de ce qu’on appelle la « génomique du paysage ». Cette dernière implique entre autre chose, le séquençage des génomes de différentes variétés de bétail provenant de plusieurs régions, et la recherche des signatures génétiques associées à leur adaptation à un environnement particulier.

Les experts de l’ILRI considèrent la génomique du paysage comme étant particulièrement importante vu l’accélération du changement climatique qui impose à l’éleveur de répondre toujours plus rapidement et avec l’expertise voulue à l’évolution des conditions de terrain. Mais ils soulignent qu’en Afrique en particulier, la capacité des éleveurs à s’adapter aux nouveaux climats va dépendre directement de la richesse du continent en termes de diversité de son cheptel indigène.

« Nous assistons trop souvent à des efforts qui visent à améliorer la productivité du bétail dans la ferme africaine en supplantant le cheptel indigène par des animaux importés qui à long terme s’avéreront mal adaptés aux conditions locales et vont demander un niveau d’attention simplement trop onéreux pour la plus part des petits exploitants agricoles, » dit Carlos Seré, Directeur général de l’ILRI. « Les communautés d’éleveurs marginalisées ont avant tout besoin d’investissement en génétique et en génomique qui leur permettront d’accroitre la productivité de leur cheptel africain, car ce dernier reste le mieux adapté à leurs environnements. »

M. Seré souligne la nécessité de nouvelles politiques qui encouragent les éleveurs et les petits exploitants agricoles africains à conserver les races locales plutôt que de les remplacer des animaux importés. Ces politiques, dit-il, devraient comprendre des programmes d’élevage centrés sur la l’amélioration de la productivité du cheptel indigène comme alternative à l’importation d’animaux.

Steve Kemp, qui dirige l’équipe de génétique et de génomique de l’ILRI, ajoute que les mesures de conservation en exploitation doivent également s’accompagner d’investissements en faveur de la préservation de la diversité qui permettront de geler le sperme et les embryons. On ne peut en effet exiger du seul exploitant agricole qu’il renonce à une augmentation de la productivité au nom de la conservation de la diversité.

« Nous ne pouvons pas attendre de l’exploitant qu’il sacrifie son revenu avec pour seul objectif de préserver le potentiel de diversité, » explique M. Kemp. « Nous savons que la diversité est essentielle pour relever les défis auxquels l’exploitant africain est confronté, mais les caractéres de grande valeur qui seront importants pour l’avenir ne sont pas toujours évidents dans l’immédiat. »

M. Kemp recommande une nouvelle approche pour mesurer les ressources génétiques du cheptel. Aujourd’hui, dit-il, l’estimation de ces caractéristiques porte essentiellement sur des éléments tels que la valeur de la viande, du lait, des œufs et de la laine, mais elle ne prend pas en compte d’autres attributs qui pourraient avoir une importance égale, voire supérieure, pour l’éleveur, qu’il soit en Afrique ou dans une autre région en développement. Ces attributs comprennent la capacité d’un animal à tirer la charrue, à fournir de l’engrais, à faire office de banque ou compte d’épargne ambulant, et d’être une forme efficace d’assurance contre les pertes de récolte.

Mais l’association de ces multiples attributs avec l’ADN d’un animal exige de nouveaux moyens pour rechercher et comprendre les caractéristiques du cheptel dans une région caractérisée par une grande diversité et une grande variété d’environnements.

« On dispose aujourd’hui des outils nécessaires, mais nous avons besoin de la volonté, de l’imagination et des ressources avant qu’il ne soit trop tard, » indique M. Kemp.