Research by ILRI is helping pastoralists in the Kitengela ecosystem better manage their land, animal and wildlife resources (photo: ILRI/Stevie Mann).

A paper by the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) that shares experiences from a project that worked to help Kenyan pastoralists better manage their lands, livestock and wildlife resources has won the 2012 Sustainability Science Award.

The yearly award is given by the Ecological Society of America to the authors of a peer-reviewed paper published in the preceding five years that makes the greatest contribution to the emerging science of ecosystem and regional sustainability through the integration of ecological and social sciences.

The winning paper, ‘Evolution of models to support community and policy action with science: Balancing pastoral livelihoods and wildlife conservation in savannas of East Africa’, was published in 2009 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), a prestigious American science journal. The paper shared experimental work in boundary-spanning research from the Reto-o-Reto (Maasai for ‘I help you, you help me’) project, which was implemented between 2003 and 2008 to help balance action in poverty alleviation and wildlife conservation in four pastoral ecosystems in East Africa, including the Kitengela pastoral ecosystem just south of Nairobi National Park.

Lessons from this project supported the development and adoption of a land-use master plan in Kitengela, which is now helping Maasai pastoralists better manage their land, animal and wildlife resources.

The announcement of this award comes at an appropriate time, just as an inception workshop takes place on ILRI’s Nairobi campus this week (Jun 5-7) for the eastern and southern Africa component of a CGIAR Research Program on Dryland Agriculture.

The following story, written by ILRI consultant Charlie Pye-Smith in 2010, shares experiences of pastoralists in Kitengela, their challenges and their hopes, as a result of this award-winning project.

Saving the plains

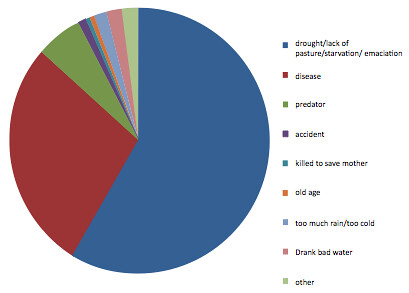

Talk to the Maasai who herd their cattle across the Athi-Kaputiei Plains to the south of Nairobi and they’ll tell you that the last (2009–2010) drought was one of the worst in living memory. ‘Many people lost almost all their livestock,’ says pastoralist William Kasio. ‘The vultures were so full they couldn’t eat any more. Even the lions had had enough.’

At the slaughterhouse in Kitengela, over 20,000 emaciated cattle were burned and buried during the drought, and the surrounding plains were littered with sun-bleached carcasses. But for the Maasai, droughts are nothing new, and indeed many believe there is an even graver threat to their survival as cattle herders. ‘Land sales, and the subdivision and fencing off of open land—that’s been the biggest problem we’ve faced in recent years,’ says Kasio, chairman of a marketing organization based at the slaughterhouse.

A generation ago, livestock and wildlife ranged freely across the plains. Today, their movements are hindered by fences, roads, quarries, cement works, flower farms and new buildings. If the development trends of the past decade continue, then the pastoral way of life, and the great wildlife migrations in and out of Nairobi National Park, could become little more than a memory. But now, thanks to a community-inspired planning exercise, there’s a good chance this won’t happen.

The Athi-Kaputiei land-use ‘master plan’, launched in 2011, provides the local council with the legislative teeth it needs to ensure that large expanses of land remain free of fencing, and that new developments are confined to specific areas. ‘We see the master plan as our survival strategy,’ says Stephen Kisemei, a member of Olkejuado County Council. ‘It means we can now plan for the future in a way we never could before.’

The master plan is the culmination of years of research and discussion involving local communities, the council, central government and a range of organizations involved in conservation and animal husbandry. ‘It’s been a very democratic process,’ explains Ogeli Makui of the African Wildlife Foundation. ‘The council and the Department of Physical Planning drafted the master plan, but the Maasai landowners’ associations and other local groups were closely involved in all the discussions.’

Since 2004, teams of young Maasai have helped to draw up maps, which illustrate the scale of land sales and the loss of open rangeland. Managed by ILRI, the mapping program and the associated research showed just how rapidly life has changed on the plains over recent years, and provided much of the data used in the master plan.

At the end of the 19th century, the Athi-Kaputiei Plains were said to boast the most spectacular concentration of wildlife in East Africa. In those days, there were four times as many wild herbivores as there were cattle. Now the reverse is true, with the wildlife beating a steady retreat.

Between 1977 and 2002, the wildlife populations in the plains to the south of Nairobi National Park fell by over 70%. Particularly hard hit were migratory animals such as wildebeest, which traditionally graze in the national park during the dry season and move south in search of new pasture during the wet season. From nearly 40,000 migrating animals in the 1970s, wildebeest numbers have fallen to about 1000 today.

ILRI research suggests that two factors are to blame: poaching, and the loss of habitat and open space. The sub-division of land, frequently followed by the erection of fences, has also made it harder for the pastoralists to move their animals around in search of water and fresh pasture. Paradoxically, the Maasai are partly to blame, as they voted for the privatization of communal ranches in the 1980s. All of a sudden, many families realized they were sitting, within gazing distance of Nairobi, on valuable real estate. Land sales rapidly increased, new developments proliferated and the population of Kitengela almost trebled during the 1990s, from 5,500 to over 17,000.

‘When I was a child in the 1970s,’ recalls Ogeli Makui, as he sips tea outside a shopping mall in Kitengela, ‘there were just a few small stalls here, nothing else. I can remember one year when there were so many wildebeest migrating across this area, followed by packs of wild dogs, that my father told me to drive our sheep home to keep them safe.’ Nowadays, speeding lorries are the main danger.

Even before ILRI produced its first maps, conservationists realized something had to be done to keep the migratory routes open. A Wildlife Conservation Lease Programme, launched in 2000, encouraged pastoralists to keep their land open by paying them 300 shillings (USD4) per acre per year. By 2010, 275 families, owners of some 30,000 acres, had signed up to the latest lease scheme.

The lease scheme is helping to protect one of East Africa’s five great migratory routes, but it isn’t enough on its own to prevent further losses of wildlife, says Jan de Leeuw, head of ILRI’s pastoral livelihoods group. ‘The master plan will certainly help, and it’s a very important step towards improving the management of the plains, but it’s also imperative that we improve the financial situation of the pastoralists to a level where they become the champions of conservation,’ he says.

The better off the Maasai are, the more sympathetic they are likely to be to wildlife conservation, even if they occasionally lose livestock to lions and other predators. The Kitengela Conservation Programme, which is managed by the African Wildlife Foundation, is currently promoting various business enterprises, including community-based tourism, and ILRI is providing support for pastoralists to improve the marketing of their livestock. All this will help, says de Leeuw.

This is one of the few places in the world where you can see major wildlife populations, including 24 species of large mammals, grazing and hunting using your top rifle scopes, often in the company of Maasai cattle. Little wonder, then, that there are conflicts between conservation and development, and sometimes between wildlife and the Maasai. Some of these conflicts will persist—the locals are deeply concerned, for example, about the building of a new town for Nairobi slum-dwellers—but the master plan provides the local council, for the first time, with the means to control development.

‘I’m very optimistic,’ says Councillor Kisemei. ‘I think the master plan will help us to secure the future for the Maasai and for the wildlife. And if we succeed, it will provide a model which could be used in other areas where wildlife and humans live close together.’

Pastoralists still vulnerable

Despite the successes of projects such as Reto-o-Reto in helping pastoral groups, governments and policymakers work together to better manage the resources in pastoral lands; pastoralists are still vulnerable to drought and changes in land use. Scientists from Colorado State University and ILRI have looked at how modelled scenarios relating to factors like access to forage, water and fuel tied to decisions made by pastoralists at household level. Stressors like drought remain a major threat to pastoral livelihoods and more so in areas where livestock compete with wildlife.

The research, carried out in Kenya’s Kajiado District, was published in a paper: ‘Using coupled simulation models to link pastoral decision making and ecosystem services.’ It evaluates pastoralist household wellbeing if access to reserve grazing is lost and the impact of compensation for those who lose access to grazing. The study showed that even though pastoralists that lose access to pasture are likely to experience large livestock losses, those in areas where livestock do not compete with wildlife have greater resilience to drought.

‘Maintaining access to reserve grazing lands is essential in helping pastoralists cope during severe drought,’ said Philip Thornton, a scientist with ILRI and one of the authors of the report. ‘We also found that compensating pastoralists for loss of access to reserve grazing lands increased their resilience.’

The above Kitengela story was written by ILRI consultant Charlie Pye-Smith.

For more on ILRI’s recent award, see: ILRI pastoral research team wins Sustainable Science Award, by Jane Gitau.

Download ‘Evolution of models to support community and policy action with science: Balancing pastoral livelihoods and wildlife conservation in savannas of East Africa’, by R S Reid, D Nkedianye, M Y Said, D Kaelo, M Neselle, O Makui, L Onetu, S Kiruswa, N Ole Kamuaroa, P Kristjanson, J Ogutu, S B BurnSilver, M J Golman, R B Boone, K A Galvin, N M Dickson, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 3 Nov 2009.

Download ‘Using coupled simulation models to link pastoral decision making and ecosystem services’, by R B Boone, K A Galvin, S B BurnSilver, P K Thornton, D S Ojima, and J R Jawson, Ecology and Society 16(2): 6, 1 Jun 2011.

Read more about the CGIAR Research Program on Dryland Systems and more on ILRI’s news blogs (below) about the three-day planning workshop for this program, which ends today:

ILRI Clippings Blog: Foolhardy? Or just hardy? New program tackles climate change and livestock markets in the Horn, 7 Jun 2012.

ILRI Clippings Blog: Supporting dryland pastoralism with eco-conservancies, livestock insurance and livestock-based drought interventions, 5 Jun 2012.

ILRI Clippings Blog: CGIAR Drylands Research Program sets directions for East and Southern Africa, 4 Jun 2012.

People, Livestock and Environment at ILRI Blog: Taming Africa’s drylands to produce food, 5 Jun 2012.

People, Livestock and Environment at ILRI Blog: Collaboration in drylands research will achieve greater impact, 5 Jun 2012.