At the 79th General Session of the United Nations World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE), in Paris in May 2011, ILRI’s Jeff Mariner (second from right) stands among a group of distinguished people heading work responsible for the eradication of rinderpest, a status officially declared at this meeting (image credit: OIE).

Several world bodies are celebrating what is being described as ‘the greatest achievement in veterinary medicine’: the eradication of only the second disease from the face of the earth.

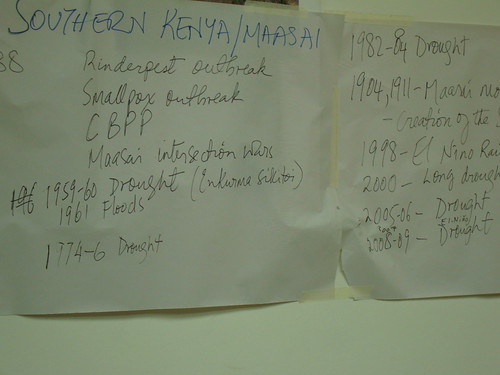

The disease is rinderpest, which means ‘cattle plague’ in German. It kills animals by a virus—and people by starving them through massive losses of their livestock.

‘In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries,’ reports the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), ‘the disease devastated parts of Africa, triggering extensive famines. . . . After decades of efforts to stamp out a disease that kept crossing national borders, countries and institutions agreed they needed to coordinate their efforts under a single, cohesive programme. In 1994, the Global Rinderpest Eradication Programme (GREP) was established at the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), in close association with the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE).

‘Excellent science, a massive vaccination effort, close international coordination and the commitment of people at all levels have helped make rinderpest eradication possible.

‘On June 28, 2011, FAO’s governing Conference will adopt a resolution officially declaring that rinderpest has been eradicated from animals worldwide. The successful fight against rinderpest underscores what can be achieved when communities, countries and institutions work together.’

Australian Peter Doherty, 1996 winner of the Nobel Prize for Medicine who served on the board of trustees of the International Laboratory for Research on Animal Diseases (ILRAD), a predecessor of ILRI (photo credit: published on the Advance website).

Australian Peter Doherty, an immunologist who is the only veterinarian to win the Nobel Prize, for Physiology or Medicine, in 1996, and who served as chair of the board of trustees research program of the International Laboratory for Research on Animal Diseases (ILRAD), a predecessor of the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), is attending the FAO ceremonies this week. In an interview with FAO, he said:

Vaccine research is currently a very dynamic area of investigation and with sufficient investment and the enthusiastic participation of industry partners at the “downstream” end, we can achieve even better vaccines against many veterinary and human diseases.

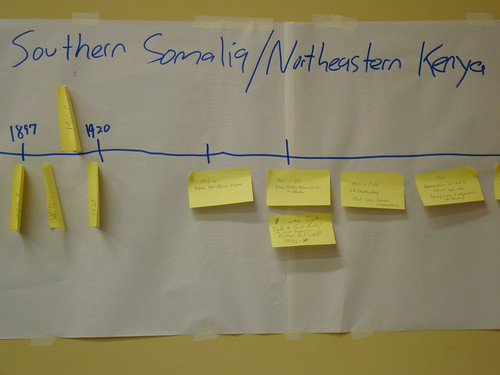

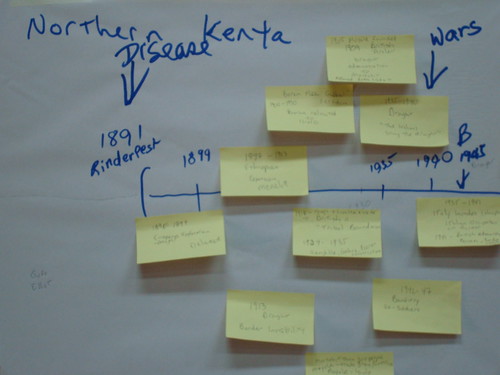

The Washington Post in May reported that ‘the World Organization for Animal Health, at its annual meeting in Paris on Wednesday, accepted documentation from the last 14 countries that they were now free of rinderpest. The organization, which goes by its French acronym, OIE, was started in 1924 in response to a rinderpest importation in Europe.

‘The most recent recorded outbreak occurred in Kenya in 2001. Much of the past decade has been spent looking for new cases, in domesticated animals and in the wild, wandering herds of ungulates, or hoofed animals, in East Africa. The last place of especially intense surveillance was Somalia, where the final outbreak of smallpox occurred in 1977.

‘“There are a huge number of unsung heroes in lots of countries that made this possible,” said Michael Baron, a rinderpest virologist at the Institute for Animal Health in Surrey, England. “In most places, they were ordinary veterinary workers who were doing the vaccination, the surveillance, the teaching.”

‘Three things made rinderpest eradicable. Animals that survived infection became immune for life. A vaccine developed in the 1960s by Walter Plowright, an English scientist who died last year at 86, provided equally good immunity. And even though the virus could infect wild animals, it did not have a reservoir of host animals capable of carrying it for prolonged periods without becoming ill.

‘In 1994, the FAO launched an eradication program that was largely financed by European countries, although the United States, which never had rinderpest, also contributed money. The effort consisted of massive vaccination campaigns, which were made more practicable when two American researchers made a version of the Plowright vaccine that required no refrigeration. . . .’

One of those researchers was Jeffrey Mariner, now working at ILRI, in Nairobi, Kenya. Mariner also helped in surveillance work ‘with a technique called “participatory epidemiology” in which outside surveyors meet with herdsmen and ask open-ended questions about the health of their animals and when they last noticed certain symptoms.

‘“It was local knowledge that really helped us trace back the last places where transmission occurred—sitting down underneath a tree in the shade, listening to storytelling,” said Lubroth, of the FAO. . . .’

Read the whole article in the Washington Post, Rinderpest, or ‘cattle plague,’ becomes only second disease to be eradicated, 27 May 2011.

Read FAO’s interview of Peter Doherty: Healthier animals, healthier people, June 2011.