A vaccine is being made available to save the lives of a million cattle in sub-Saharan Africa against a lethal disease and to help safeguard the livelihoods of people who rely on their cattle for their survival.

East Coast fever is a tick-transmitted disease that kills one cow every 30 seconds. It puts the lives of more than 25 million cattle at risk in the 11 countries of sub-Saharan Africa where the disease is now endemic. The disease endangers a further 10 million animals in regions such as southern Sudan, where it has been spreading at a rate of more than 30 kilometres a year. While decimating herds of indigenous cattle, East Coast fever is an even greater threat to improved exotic cattle breeds and is therefore limiting the development of livestock enterprises, particularly dairy, which often depend on higher milk-yielding crossbred cattle. The vaccine could save the affected countries at least a quarter of a million US dollars a year.

Registration of the East Coast fever vaccine is central to its safety and efficacy and to ensuring its sustainable supply through its commercialization. The East Coast fever vaccine has been registered in Tanzania for the first time, a major milestone that will be recognized at a launch event in Arusha, northern Tanzania, on May 20. Recognizing the importance of this development for the millions whose cattle are at risk from the disease, governments, regulators, livestock producers, scientists, veterinarians, intellectual property experts, vaccine distributors and delivery agents as well as livestock keepers – all links in a chain involved in getting the vaccine from laboratory bench into the animal – will be represented.

An experimental vaccine against East Coast fever was first developed more than 30 years ago at the Kenyan Agricultural Research Institute (KARI). Major funding from the UK Government’s Department for International Development (DFID) and others enabled work to produce the vaccine on a larger scale. When stocks from 1990s ran low, the Africa Union/Interafrican Bureau for Animal Resources and chief veterinary officers in the affected countries asked the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) to produce more and ILRI subsequently produced a million doses of the vaccine to fill this gap. But the full potential for livestock keepers to benefit from the vaccine will only be achieved through longer term solutions for the sustainable production, distribution and delivery of the vaccine.

With $28US million provided by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and DFID, a not-for-profit organization called GALVmed (Global Alliance for Livestock Veterinary Medicines) is fostering innovative commercial means for the registration, commercial distribution and delivery of this new batch of the vaccine. A focus on sustainability underpins GALVmed’s approach and the Global Alliance is bringing public and private partners together to ensure that the vaccine is available to those who need it most.

Previous control of East Coast fever relied on use of acaracide dips and sprays, but these have several drawbacks. Ticks can develop resistance to acaracides and regular acaricide use can generate health, safety and environmental concerns. Furthermore, dipping facilities are often not operational in remote areas.

This effective East Coast fever vaccine uses an ‘infection-and-treatment method’, so-called because the animals are infected with whole parasites while being treated with antibiotics to stop development of disease. Animals need to be immunized only once in their lives, and calves, which are particularly susceptible to the disease, can be immunized as early as 1 month of age.

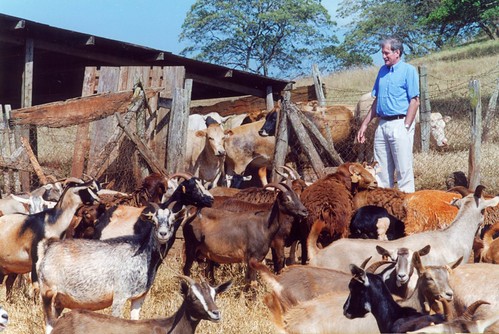

Over the past several years, the field logistics involved in mass vaccinations of cattle with the infection-and-treatment method have been greatly improved, due largely to the work of a private company, VetAgro Tanzania Ltd, which has been working with Maasai cattle herders in northern Tanzania. VetAgro has vaccinated more than 500,000 Tanzanian animals against East Coast fever since 1998, with more than 95% of these vaccinations carried out in remote pastoral areas. This vaccination campaign has reduced calf mortality in herds by 95%. In the smallholder dairy sector, vaccination reduced the incidence of East Coast fever by 98%. In addition, most smallholder dairy farmers reduced their acaracide use by at least 75%, which reduced both their financial and environmental costs.

Notes for Editors

What is East Coast fever?

East Coast fever is caused by Theleria parva (an intracellular protozoan parasite), which is transmitted by the brown ear tick Rhipicephalus appendiculatus. The parasites the tick carries make cattle sick, inducing high fever and lympho-proliferative syndrome, usually killing the animals within three weeks of their infection.

East Coast fever was introduced to southern Africa at the beginning of the twentieth century with cattle imported from eastern Africa, where the disease had been endemic for centuries. This introduction caused dramatic cattle losses. The disease since then has persisted in 11 countries in eastern, central and southern Africa – Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Rwanda, Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe. The disease devastates the livelihoods of small-scale mixed crop-and-livestock farmers, particularly smallholder and emerging dairy producers, as well as pastoral livestock herders, such as the Maasai in East Africa.

The infection-and-treatment immunization method against East Coast fever was developed by research conducted over three decades by the East African Community and the Kenya Agricultural Research Institute (KARI) at Muguga, Kenya (www.kari.org). Researchers at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), in Nairobi, Kenya (www.ilri.org), helped to refine the live vaccine. This long-term research was funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID) (www.dfid.gov.uk) and other donors of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) (www.cgiar.org).

The first bulk batch of the vaccine, produced by ILRI 15 years ago, has protected one million animals against East coast fever, with the survival of these animals raising the standards of living for many livestock keepers and their families. Field trials of the new vaccine batch, also produced at ILRI, were completed in accordance with international standards to ensure that it is safe and effective.

How is the vaccine stored and administered?

Straws of the East Coast fever vaccine are stored in liquid nitrogen until needed, with the final preparation made either in an office or in the field. The vaccine must be used within six hours of its reconstitution, with any doses not used discarded. Vaccination is always carried out by trained veterinary personnel working in collaboration with livestock keepers. Only healthy animals are presented for vaccination; a dosage of 30% oxytetracycline antibiotic is injected into an animal’s muscle while the vaccine is injected near the animal’s ear. Every animal vaccinated is given an eartag, the presence of which subsequently increases the market value the animal. Young calves are given a worm treatment to avoid worms interfering with the immunization process.

Note

Case studies illustrating the impact of the infection-and-treatment vaccine on people’s lives are available on the GALVmed website at: www.galvmed.org/path-to-progress

For more information about the GALVmed launch of the live vaccine, on 20 May 2010, in Arusha, Tanzania, go to www.galvmed.org/

Also called elephant grass, Napier grass is planted on farms across East Africa as a source of feed for dairy cows. Farmers cut the grass for their livestock, carrying it home for stall feeding.

Also called elephant grass, Napier grass is planted on farms across East Africa as a source of feed for dairy cows. Farmers cut the grass for their livestock, carrying it home for stall feeding.