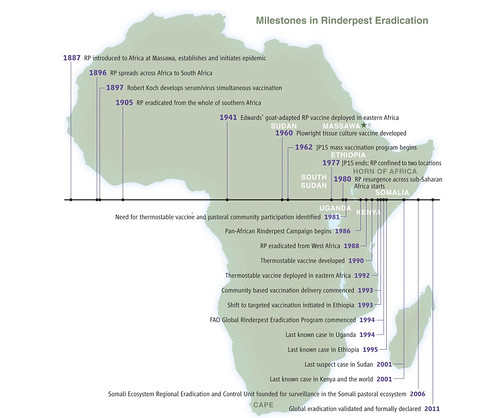

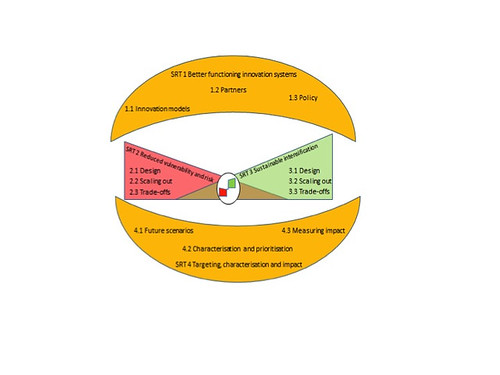

A timeline of major events in the history of rinderpest in Africa from its introduction in 1887, in military cattle brought to Eritrea to feed troops, to the declaration of rinderpest’s eradication in 2011. RP, rinderpest. (Illustration credit: Figure 1 in ‘Rinderpest eradication: Appropriate technology and social innovations’, 2010, by Jeffrey Mariner et al. Science 337, 1309.)

The invention of sex and death, evolutionary biologists tell us, allowed organisms to escape wholesale extermination by parasitic infections. The invention of antibiotics and other miracles of modern medicine allows many of us, particularly in rich countries, to think we can escape most disease, if not death. This of course is over-optimistic and flies in the face of all of human history. Disease has altered those histories, stamped whole continents with its imprint, shaped global affairs—bubonic plague in 14th-century Europe, smallpox in the Americas in the 16th century following European invasion, potato blight in 19th-century Ireland, the Spanish flu pandemic that circled the world in 1918, malaria and HIV/AIDS in Africa today.

Some of the most important diseases have killed human populations indirectly, by annihilating the crops and animals that sustained us. This happened when late blight affected the potato crop in Ireland in the 1840s, killing some 1 million people and causing another 1.5 million to emigrate in The Great Hunger, and when brown spot of rice ruined crops in Bangladesh and eastern India in 1943, leading to the deaths of 2 million or more people in The Bengal Famine.

Among the latter ‘food plagues’ is a remarkably little-known viral disease of cattle and other ungulates that ‘has been blamed for speeding the fall of the Roman Empire, aiding the conquests of Genghis Khan and hindering those of Charlemagne, opening the way for the French and Russian revolutions, and subjugating East Africa to colonization (Rinderpest, scourge of cattle, is vanquished, New York Times, 27 Jun 2011).

Rinderpest, a German term meaning ‘cattle plague’, is a viral disease related to measles (recent evidence suggests the measles virus may have diverged from the rinderpest virus during the Middle Ages). It is arguably the most important animal disease historically. It entered the Horn of Africa from the port of Massawa, in what is now Eritrea, in 1887 with an invading Italian army that was importing Indian cattle for food and draft power.

The virus exploded so fast that it reached South Africa within a decade (and is considered one of the factors that impoverished Boer farmers as war with the English approached). It doomed East Africa’s wandering herders, subsisting on milk mixed with cow blood. Historians believe a third of them or more starved to death—Rinderpest, scourge of cattle, is vanquished, New York Times, 27 Jun 2011.

Killing animals within days of infection, the rinderpest epidemic emptied East Africa of most of its large grazing animal populations, wiping out 80–90 per cent of the region’s cattle, which, it is argued, left the remaining population too weak from hunger to oppose European colonialism.

Rinderpest struck East Africa in 1890, and in two years 95 percent of the buffalo and wildebeest there had died. So began a series of events of such profound ecological importance that the repercussions are still being felt today.—A R E Sinclair and M Norton-Griffiths, editors, Serengeti: Dynamics of an Ecosystem, 1979.

Journalist Fred Pearce gives more details.

Great pastoral civilizations across the continent were shattered. Central African cattle-rearing tribes like the Tutsi and Karamajong starved, along with Sudanese nations like the Dinka and Bari, West Africans like the Fulani, and southern Africans like the Nama and Herero. The folklore of the Maasai of East Africa tells of the enkidaaroto, the “destruction,” of 1891. They lost most of their cattle, and two-thirds of the Maasai died. One elder later recalled that the corpses were “so many and so close together that the vultures had forgotten how to fly.”

Many of these societies never recovered their numbers, let alone their wealth and power. Rinderpest served up the continent on a plate for European colonialists. In its wake, the Germans and British secured control of Tanzania and Kenya with barely a fight. In southern Africa, the hungry and destitute Zulus migrated to the gold mines of Witwatersrand, helping to create the brutal social divide between black and white from which apartheid sprang.

It is an extraordinary story, rarely told. . . .

Fred Pearce: Why Africa’s national parks are failing to save wildlife, Yale Environment 360, 19 Jan 2010.

Dan Charles, of National Public Radio, in the USA, reports on an article published in Science this month demonstrating that it was African cattle herders that wiped this ancient plague from the face of the Earth.

‘Twice in all of history, humans have managed to eradicate a devastating disease. You’ve heard of the first one, I suspect: smallpox. But rinderpest? . . .

‘In this week’s issue of the journal Science, several of the architects of rinderpest’s elimination lay out the reasons for their success. The key innovation wasn’t technological, they say. It was social and cultural.

‘Technology certainly played a part. Half a century ago, a British veterinarian named Walter Plowright, working in Kenya, created the first truly effective and safe vaccine for rinderpest. . . .

‘Later, Jeffrey Mariner of the Tufts Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine, developed a version of the vaccine that didn’t need to be refrigerated, allowing veterinarians to use it far from roads and electricity.

‘Yet the disease persisted in Africa, surviving in remote areas plagued by weak government and chronic conflict, such as southern Sudan and parts of Uganda, Ethiopia, and Somalia. Veterinarians rarely ventured into those areas, and it was hard to know where vaccinations were even needed because government officials were reluctant to report outbreaks.

Mariner, who now works at the International Livestock Research Institute in Kenya, says that ultimately, the skills and knowledge of nomadic cattle herders who lived in those hard-to-reach areas were the keys to cracking the rinderpest puzzle.

“Those farmers could tell us where outbreaks were occurring,” Mariner tells The Salt, speaking by phone from Nairobi. In addition, some nomadic farmers got training as “community animal health workers” and were able to carry out vaccinations themselves. They proved better at the job than veterinarians, in part because they knew their animals. . . .

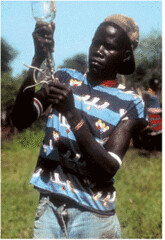

Tom Olaka, a community animal health worker in Karamajong, northern Uganda, was part of a vaccination campaign in remote areas of the Horn of Africa that drove the cattle plague rinderpest to extinction in 2010 (photo credit Christine Jost).

‘Tom Olaka, a community animal health worker in the border region between Uganda, Sudan, and Kenya, identified and reported the last outbreak of rinderpest in 2000. The virus was officially declared extinct last year. Around the world, cattle farmers can breathe just a little easier.’

Read the whole article by Dan Charles at NPR: How African Cattle Herders Wiped Out An Ancient Plague, 14 Sep 2012.

Read the ILRI News Blog about this: New analysis in ‘Science’ tells how world eradicated deadliest cattle plague from the face of the Earth, 13 Sep 2012.

Read the paper in Science (subscription required to read full text): Rinderpest eradication: Appropriate technology and social innovations, by Jeffrey Mariner, James House, Charles Mebus, Albert Sollod, Dickens Chibeu, Bryony Jones, Peter Roeder, Berhanu Admassu, Gijs van ’t Klooster, 14 September 2012, Vol. 337 no. 6100 pp. 1309–1312, DOI: 10.1126/science.1223805.

Read previous articles on the ILRI News and Clippings blogs about the eradication of rinderpest:

ILRI’s Jeff Mariner speaks on what he learned from the eradication of rinderpest–and his new fight against ‘goat plague’, 15 Sep 2012.

Goat plague next target of veterinary authorities now that cattle plague has been eradicated, 4 Jul 2011.

Deadly rinderpest virus today declared eradicated from the earth–’greatest achievement in veterinary medicine’, 28 Jun 2011.

Why technical breakthroughs matter: They helped drive a cattle plague to extinction, 28 Oct 2010.