.jpg!Blog.jpg)

‘Southern Gardens’ by Paul Klee, 1921 (via WikiPaintings).

An ongoing CGIAR group meeting in Bodega Bay, California, (18–19 Mar 2013) is looking at untapped potential in CGIAR and beyond for actors of diverse kinds to join forces in improving global food security in the light of climate change. Updates from the event are being shared on the CCAFS website and on Twitter (follow #2013CCSL). For more information, go to CCAFS 2013 Science Meeting programme. More information about the meeting is here.

The following opinion piece was drafted by Patti Kristjanson, of the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) and based at the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF), in Nairobi, Kenya, with inputs from other ‘climate change and social media champions’, including Sophie Alverez (International Center for Tropical Agriculture [CIAT]), Liz Carlile (International Institute for Environment and Development [IIED]), Pete Cranston (Euforic Services), Boru Douthwaite (WorldFish), Wiebke Foerch (CCAFS), Blane Harvey (International Development Research Centre [IDRC]), Carl Jackson (Westhill Knowledge Group), Ewen Le Borgne (International Livestock Research Institute [ILRI]), Susan MacMillan (ILRI), Philip Thornton (CCAFS/ILRI) and Jacob van Etten (Bioversity International). (Go here for a list of those participating at the CCAFS Annual Science Meeting in California).

Untapped potential

All humans possess the fundamental capacity to anticipate and adapt to change. And of course experts argue that it is change — whether the end of the last Ice Age or the rise of cities or the drying of a once-green Sahel — that has driven our evolution as a species. If we’ve progressed, they say, it’s because we had to. And we can see in the modern world that, with supportive and encouraging environments, both individuals and communities can be highly resourceful and innovative, serving as agents of transformation. The agricultural, industrial and information revolutions were the products of both individual inventiveness (think of Steve Jobs) and social support (Silicon Valley).

Some of the major changes today are occurring fastest in some of the world’s slowest economies. The two billion or so people in the world’s developing countries who grow and sell food for a living, for example, are adjusting to huge changes — to their countries’ exploding populations and diminishing natural resources, to a rural exodus and rush to the cities, to higher food prices, to new lethal diseases, to a single global economy, and, on top of all of that, to a changing climate causing unpredictable seasons and more extreme and frequent ‘big weather’ in the form of droughts, floods and storms.

PETE CRANSTON

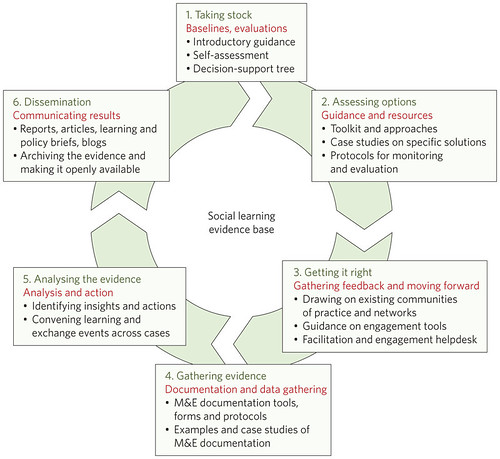

The problems generated by climate change requires larger scale, collaborative responses — that is, social learning, requiring collaborative reflection and learning, at scale, and engaging community decision-making processes. Collective action, at scale, to systemic problems caused by climate change is the area of interest that came out of a workshop on climate change and social learning held in May 2012.

[The workshop Cranston refers to, held on ILRI’s campus in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, was organized by CCAFS; go here for more information.]

When it comes to the food systems that support all of us, that enable human life itself, we’re squandering our innate potential to innovate. What will it take to unleash the potential within all of us — consumers and farmers and farm suppliers, food sellers and agri-business players, agricultural scientists, policymakers, thought leaders, government officials, development experts, humanitarian agents — to make the changes we need to make to feed the world? And what will it take to do so in ways that don’t destroy the natural resource base on which agriculture depends? In ways that don’t leave a legacy of ruined landscapes for our children and children’s children to inherit?

PATTI KRISTJANSON

You don’t hear much about what can be done about it. We need to see major changes in how food is grown and distributed. In Africa and Asia, where millions of families live on one to five hectares of land, we need to see improved farming systems. We need to see transformative changes, not small changes. But to transform food systems, we also need to transform how the research that supports these transformations is done. We need to think more about partnerships. And learning.

.jpg!Blog.jpg)

‘Remembrance of a Garden’ by Paul Klee, 1914 (via WikiPaintings).

How did we get here?

Before attempting to answer those questions, it might profit us to take a look at how agricultural development got to where it is now. Alain de Janvry, a professor of agricultural and resource economics at the University of California at Berkeley, and others argue as follows.

For decades, development agencies put agriculture at the forefront of their priorities, believing it to be the precursor to industrialization. Then, starting in the 1970s and early 1980s, the bias for agriculture began to be seriously eroded, with huge economic, social, and environmental costs.

The good news, de Janvry says, is that ‘In recent years, a number of economic, social, and environmental crises have attracted renewed attention to agriculture as both a contributor to these problems and a potential instrument for solutions. . . . A new paradigm has started to emerge where agriculture is seen as having the capacity to help achieve several of the major dimensions of development, most particularly accelerating GDP growth at early stages of development, reducing poverty and vulnerability, narrowing rural-urban income disparities, releasing scarce resources such as water and land for use by other sectors, and delivering a multiplicity of environmental services.’

The bad news, he says, is that ‘renewed use of agriculture for development remains highly incomplete, falling short of political statements.’

Let’s now return to our questions about what’s missing in agricultural development today, and what that has to do with ‘social learning’, or lack of it.

.jpg!Blog.jpg)

‘Apparatus for the Magnetic Treatment of Plants’ by Paul Klee, 1908 (via WikiPaintings).

Unlocking the human potential for innovating solutions

Agricultural scientists are important actors both in instigating change and in helping people anticipate and adapt to climate and other agriculturally important changes. They have played a key role so far in spearheading major agricultural movements such as the Green Revolution in Asia. Yet one billion poor people have been left behind by the Green Revolution, largely because they live in highly diverse agro-ecological regions that are relatively inaccessible and where they cannot access the research-based information, technologies and support they need to improve, or ‘intensify’, their farming systems.

The complex agriculturally related challenges of today require going way beyond ‘business as usual’. And they offer agricultural scientists unprecedented opportunities to play major roles in some of the major issues of our time, including reducing our greenhouse gas emissions and adapting to climate change. But we’re not going to make good use of these opportunities if we don’t recognize and jump on opportunities for joint societal learning and actions.

POTATOES IN THE ANDES

Take this example from Latin America, where agricultural researchers set about documenting the biodiversity of potato varieties in the high-elevation Andes. An unanticipated consequence of this activity was learning from local farmers about numerous varieties previously unknown to science. And the scientists realized that traditional knowledge of these hardy varieties and other adaptive mechanisms are helping many households deal with climate variability at very high elevations. Further learning in this project showed that women and the elderly tended to have much better knowledge of traditional varieties and their use than the owners of the land. This kind of knowledge is now being shared widely in an innovative Andean regional network.

RICE IN VIETNAM

Here’s another example. Rice is now being grown by over a million farmers in Vietnam using a new management system that reduces water use and methane gas emissions while generating higher incomes for farm families. This happened through farmers — both men and women — experimenting and sharing experiences in ‘farmer field schools’ that had strong government support. It turns out that the women farmers are better trainers than men. After participating in a farmer field school, each woman helped 5–8 other farmers adopt the new approach, while every male participant helped only 1–3 additional farmers. So making sure women were a key part of this effort led to much greater success in reducing poverty and environmental damage.

.jpg!Blog.jpg)

‘Ravaged Land’ by Paul Klee, 1921, Galarie Beyeler (via WikiPaintings).

New opportunities for doing research differently

Back to de Janvry for a moment. ‘Crises and opportunities’, he says, ‘combine in putting agriculture back on the development agenda, as both a need and a possibility. This second chance in using agriculture for development calls for a new paradigm, which is still largely to be consistently formulated and massively implemented. . . [A] Green Revolution for Sub-Saharan Africa is still hardly in the making.’

ALAIN DE JANVRY

In the new paradigm, process thus matters along with product if the multiple dimensions of development are to be achieved. . . . As opposed to what is often said in activist donor circles, it is a serious mistake to believe that we know what should be done, and all that is left to do is doing it. . . . Because objectives and contexts are novel, we are entering un-chartered territory that needs to be researched and experimented with. Extraordinary new opportunities exist to successfully invest in agriculture for development, but they must be carefully identified. . . . Innovation, experimentation, evaluation, and learning must thus be central to devising new approaches to the use agriculture for development. This requires putting into place strategies to identify impacts as we proceed with new options.

The biggest mistake one could make about using agriculture for development is believe that it is easy to do and that we already know all we need to do it. It is not and we don’t. . . . Lessons must be derived from past mistakes, and new approaches devised and evaluated.

So how do we derive lessons from past mistakes? How do we devise new approaches and evaluate them on-goingly?

LIVESTOCK IN EAST AFRICA

One way is to take a proactive social learning approach — learning together through action and reflection, which leads to changes in behaviour. Researchers from ILRI, for example, learned by interacting closely with pastoral groups in East Africa that intermittent engagement is not as powerful a force of social change as is continual engagement, which they achieved by instituting ‘community facilitators-cum-researchers’. This led to transformative changes in land policy and management, with long-lasting benefits for wildlife populations, pastoral communities and rangelands alike.

Public-private partnerships that include researchers can also help. Through active learning together we can reach more people, more efficiently and effectively than before — this approach is further supported through widespread access to the internet and smartphones that allow greater engagement from communities and individuals spread far and wide. We can map the soils and water resources needed to grow food, and try new ‘crowdsourced’ approaches to identify needs for different types of seeds and seedlings. We can democratize research, and make scientists much more responsive to the needs of different groups of people.

.jpg!Blog.jpg)

‘Rising Sun’ by Paul Klee, 1907 (via WikiPaintings).

Why bother?

What’s the incentive for researchers to do things differently? For all of us, it lies in the opportunity to sharpen our edge, to become better solvers of bigger, more complex problems, or at least to ask better questions about ‘wicked problems’. For scientists in particular, the opportunity to make our research, including fundamental and lab-based research, more relevant and targeted to meeting demand — user-inspired rather than supply-driven research — is tremendous.

RICE IN AFRICA

When researchers at two international rice research institutes, IRRI and AfricaRice, started to include women in participatory varietal selection, different preferences emerged. Women focused more on food security than yields. Through working directly with women as well as men, the nature of research challenges and questions changed to accommodate different needs, values and norms. The use of farmer-to-farmer learning videos accelerated the transfer of different types of learning. Evaluations show that this approach has led to an 80% greater adoption rate of different technologies and practices than previous dissemination techniques.

In these ways, socially differentiated and participatory research approaches hold the promise of making our research more central to the major agricultural problems we’re facing — and to anticipate future problems, issues and questions by sharpening our critical questioning through ongoing learning.

.jpg!Blog.jpg)

‘Reconstructing’ by Paul Klee, 1926 (via WikiPaintings).

How do we learn and make this happen?

We learn by using, by doing, by trying, by failing, by modeling, through engagement, dialogue and reflection. Knowledge links to action more effectively when the users are involved from the problem definition stage onwards, when they ‘co-own’ the problem and questions that could lead to solving it. So a shift towards joint observation, trials, modeling and experimentation is key. CGIAR and its partners have used learning approaches to catalyze transformative change in the ways in which food is grown, distributed and consumed.

LEARNING ALLIANCES IN LATIN AMERICA

CIAT has been taking a ‘learning alliance’ approach, partnering with intermediaries such as the Sustainable Food Lab, global food and commodity corporations, local farmer associations and international development-oriented non-governmental organizations. Innovative networks have been formed that link local producers (rural poor) with global buyers. Executives from global food companies have gone on learning journeys where they hear first-hand from small farmers about 3-month periods of food insecurity; they responded by supplying alternate seed varieties for food security over this period. Global companies have reoriented their buying patterns to accommodate local producer needs. These new alliances are generating longer-term networks that are building the adaptive capacity of both food sellers and producers.

.jpg!Large.jpg)

‘Refuge’ by Paul Klee, 1930 (via WikiPaintings).

What are we asking people to do?

We want to see more people embracing the idea of joint, transformative learning, the co-creation of knowledge. This is not a new idea. But the imperatives we’re facing now demand a more conscious articulation, promotion and facilitation of this approach by a wide range of people, especially scientists from all disciplines. More relevant science leads to social credibility and legitimacy, which in turn should lead to the ability to mobilize support — a win-win for researchers.

PATTI KRISTJANSON

To enable social learning, incentives and institutions — the rules of the game — have to change also. This includes our changing how research is planned, evaluated and funded. We need much longer time horizons than those currently in play (with 2–3 year projects the norm). And we need to share this critical lesson with governments and other investors in agricultural research for development.

Our vision of success includes many more scientists engaged in broad partnerships; producing more relevant, useful and used information; doing less paperwork and more mentoring of young people and more interactive science; and more generously sharing their knowledge. This helps us to see — much more clearly than before — our scientific contributions to improved agricultural landscapes, sustainable food systems, profitable and productive livelihoods, and improved food security globally.

EWEN LE BORGNE

For more on social learning, consult these ‘social learning gurus’ cited by Ewen Le Borgne:

• Mark Reed, author of the definition that a few of us have been quoting — see his What is social learning? response to a paper published in Ecology and Society in 2010.

• Harold Jarche or Jane Hart, both write well on social learning in an enterprise — see Social Learning Centre website and Jarche’s blog.

• Sebastiao Ferreira Mendonca — see the Mundus maris website (Sciences and Arts for Sustainability International Initiative)

• Valerie Brown, Australian academic who worked a lot on multiple knowledges in IKM-Emergent, a five-year research program in ’emergent issues in information and knowledge management and international development’ (blog here)

For more information:

Go to CCAFS 2013 Science Meeting programme. Updates from the event are being shared on the CCAFS website and on Twitter (follow #2013CCSL).

For more on this week’s meeting, see these earlier posts on the ILRI News Blog:

The world’s ‘wicked problems’ need wickedly good solutions: Social learning could speed their spread, 18 May 2013.

Climate change and agricultural experts gather in California this week to search for the holy grail of global food security, 17 Mar 2013.

And on the CCAFS Blog:

Farmers and scientists: better together in the fight against climate change, 19 Mar 2013.

Transformative partnerships for a food-secure world, 19 Mar 2013.

Read Alain de Janvry’s whole paper: Agriculture for development: New paradigm and options for success, International Association of Agricultural Economists, 2010.

For more on the use of ‘social learning’ and related methods by the CCAFS, see the CCSL wiki and these posts on ILRI’s maarifa blog.

.jpg!Blog.jpg)

.jpg!Blog.jpg)

.jpg!Blog.jpg)

.jpg!Blog.jpg)

.jpg!Blog.jpg)

.jpg!Blog.jpg)

.jpg!Large.jpg)