Tom Olaka, a community animal health worker in Karamajong, northern Uganda, was part of a vaccination campaign in remote areas of the Horn of Africa that drove the cattle plague rinderpest to extinction in 2010 (photo credit: Christine Jost).

A superb example of why technical breakthroughs matter is reported in the current issue (22 October 2010) of the leading science journal, Science.

The eradication of rinderpest from the face of the earth, probably the most remarkable achievement in the history of veterinary science, is a milestone expected to be announced in mid-2011 pending a review of final official disease status reports from a handful of countries to the World Organisation for Animal Health.

A plague of cattle and wild ungulates, rinderpest would not have been eradicated without such a technical breakthrough. This was the development of an improved vaccine that did not require a 'cold chain' and thus could be administered in some of the most inhospitable regions in the Horn of Africa, where the virus was able to persist due to lack of vaccination campaigns in these hotspots.

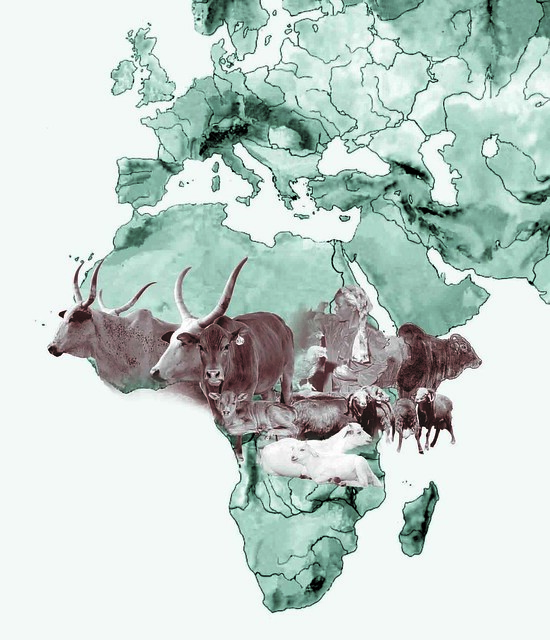

Rinderpest is a viral livestock disease that has afflicted Europe, Asia and Africa for centuries. It killed more than 90 per cent of the domesticated animals, as well as untold numbers of people and plains game, in Africa at the turn of the 19th century, a devastation so complete that its impacts are still felt today, more than a century later. The last-known outbreak of rinderpest occurred in Kenya in 2001.

The key technical breakthrough in this effort involved development of an improved vaccine against rinderpest. The original vaccine was developed at the Kenya Agricultural Research Institute (KARI) laboratories. In 1990, Jeffrey Mariner, a veterinary epidemiologist who at that time was at the Tufts Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine and working with the Africa Union-Inter-African Bureau for Animal Resources (AU-IBAR), improved the vaccine by producing a thermostable version that did not require refrigeration up to the point of use. This allowed vets and technicians to backpack the vaccine into remote war-torn areas, where vet services had broken down and international agencies dared not send personnel. The AU-IBAR led the Pan-African Rinderpest Campaign, which coordinated the efforts that resulted in the eventual eradication of rinderpest from Africa.

Now working in the Nairobi laboratories of at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), Mariner says that just as important as this technological advance was getting the development community to begin to address how people work together. Mariner and his colleagues at AU-IBAR themselves took three innovations as lessons from the rinderpest eradication campaign: (1) community-based vaccination programs, (2) participatory surveillance systems based on local knowledge, and (3) optimized control strategies that target high-risk communities through.

‘We must examine issues from the perspective of each group of stakeholders involved and visualize how proposed changes would affect them,’ says Mariner. ‘The power relationships of the groups also need to be considered. Advocates for change must then craft a new vision for how the various stakeholder groups will function that is sufficiently exciting to get people to risk change.’

Excerpts from the Science article, by Dennis Normille, follow.

'Rinderpest, an infectious disease that has decimated cattle and devastated their keepers for millennia, is gone. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) announced on 14 October in Rome that a 16-year eradication effort has succeeded and fieldwork has ended.

'“This is the first time that an animal disease is being eradicated in the world and the second disease in human history after smallpox,” FAO Director-General Jacques Diouf said in his World Food Day address in Rome the next day.

'“It is probably the most remarkable achievement in the history of veterinary science,” says Peter Roeder, a British veterinarian involved with FAO’s Global Rinderpest Eradication Programme (GREP) from its launch in 1994 until he retired in 2007. For the veterinarians who participated in the effort, the achievement is particularly poignant. . . .

'One formality remains: The Paris-based World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) still must complete the certification of a handful of countries as rinderpest free. OIE is likely to adopt an official declaration recognizing the demise of the disease at its May assembly. Meanwhile, animal-disease fighters have already been applying lessons learned from the rinderpest campaign and pondering which animal disease might be the next target for eradication.

'Although nearly forgotten in much of the West, as recently as the early 1900s, outbreaks of rinderpest—from the German for “cattle plague”—regularly ravaged cattle herds across Eurasia, often claiming one-third of the calves in any herd. The virus, a relative of those that cause canine distemper and human measles, spreads through exhaled droplets and feces of sick animals, causing fever, diarrhea, dehydration, and death in a matter of days. It primarily affects young animals; those that survive an infection are immune for life.

'When the virus hit previously unexposed herds, the impact was horrific. In less than a decade after the virus was inadvertently introduced to the horn of Africa in 1889, it spread throughout sub-Saharan Africa, killing 90% of the cattle and a large proportion of domestic oxen used for plowing and decimating wild buffalo, giraffe, and wildebeest populations. With herding, farming, and hunting devastated, famine claimed an estimated one-third of the population of Ethiopia and two-thirds of the Maasai people of Kenya and Tanzania. . . .

'In 1994, when rinderpest was entrenched in central Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, and a swath stretching from Turkey through India and to Sri Lanka, FAO brought together three regional rinderpest-control programs into GREP and set the goal of eliminating the disease by 2010. . . .

'The key technical breakthrough was the recognition that the virus was re-emerging from just a handful of reservoirs that could be the targets of intensive surveillance and vaccination campaigns. In 1990, Jeffrey Mariner, then at Tufts University School of Veterinary Medicine (now the Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine), had developed an improved vaccine that did not require refrigeration up to the point of use. This allowed vets and technicians to backpack vaccine into remote areas. One of the reservoirs was in the heart of war-torn eastern Africa, where vet services had broken down and international agencies dared not send personnel. GREP relied on local pastoralists to track the disease and on trained community animal health workers to administer the vaccine to quell outbreaks.

'. . . The virus was last detected in 2001 in wild buffaloes in Meru National Park in Kenya, on the edge of the Somali ecosystem.

'What comes next? Some veterinary experts question whether the international community is ready to take on another massive eradication campaign, but one disease mentioned as a possible eradication target is peste des petites ruminants (PPR), which is highly contagious and lethal among sheep and goats. Related to the rinderpest virus, the PPR virus has long circulated in central Africa, the Middle East, and the Indian subcontinent and has recently spread to Morocco. . . .'

ILRI's Jeff Mariner is now working on an improved vaccine for this disease.

—-

Read the whole article at Science (registration needed to read the full article): Rinderpest, deadly for cattle, joins smallpox as a vanquished disease, 22 October 2010.

To find out what the eradication of rinderpest means for livestock farmers around the world, listen to the following interview featuring John McDermott, ILRI's deputy director general.