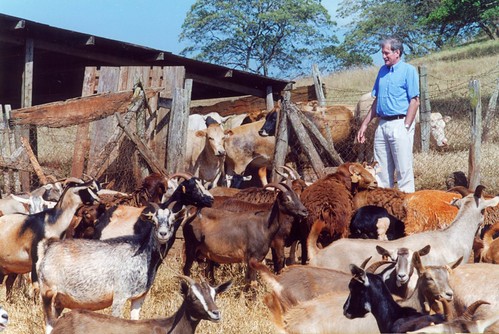

Resilient disease-resistant, 'ancient' West African cattle, such as these humpless longhorn N'Dama cattle, are among breeds at risk of extinction in Africa as imported animals supplant valuable native livestock

Urgent action is needed to stop the rapid and alarming loss of genetic diversity of African livestock that provide food and income to 70 percent of rural Africans and include a treasure-trove of drought- and disease-resistant animals, according to a new analysis presented today at a major gathering of African scientists and development experts.

Experts from the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) told researchers at the 5th African Agriculture Science Week (www.faraweek.org), hosted by the Forum for Agricultural Research in Africa (FARA), that investments are needed now to expand efforts to identify and preserve the unique traits, particularly in West Africa, of the continent's rich array of cattle, sheep, goats and pigs developed over several millennia but now under siege. They said the loss of livestock diversity in Africa is part of a global 'livestock meltdown'. According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, some 20 percent of the world's 7616 livestock breeds are now viewed as at risk.

'Africa's livestock are among the most resilient in the world yet we are seeing the genetic diversity of many breeds being either diluted or lost entirely', said Abdou Fall, leader of ILRI's livestock diversity project for West Africa. 'But today we have the tools available to identify valuable traits in indigenous African livestock, information that can be crucial to maintaining and increasing productivity on African farms.'

Fall described a variety of pressures threatening the long-term viability of livestock production in Africa. These forces include landscape degradation and cross-breeding with 'exotic' breeds imported from Europe, Asia and the America.

For example, disease-susceptible breeds from West Africa's Sahel zone are being cross-bred in large scale with breeds adapted to sub-humid regions, like southern Mali, that have a natural resistance to trypanosomosis.

Trypanosomosis kills an estimated three to seven million cattle each year and costs farmers billions of dollars each year in, for example, lost milk and meat production and the costs of medicines and prophylactics needed to treat or prevent the disease. While cross-breeding may offer short-term benefits, such as improved meat and milk production and greater draft power, it could also cause the disappearance of valuable traits developed over thousands of years of natural selection.

ILRI specialists are in the midst of a major campaign to control development of drug resistance in the parasites that cause this disease but also have recognized that breeds endowed with a natural ability to survive the illness could offer a better long-term solution.

The breeds include humpless shorthorn and longhorn cattle of West and Central Africa that have evolved in this region along with its parasites for thousands of years and therefore have evolved ways to survive many diseases, including trypanosomosis, which is spread by tsetse flies, and also tick-borne diseases. Moreover, these hardy animals have the ability to withstand harsh climates. Despite their drawbacks—the shorthorn and longhorn breeds are not as productive as their European counterparts—their loss would be a major blow to the future of African livestock productivity.

'We have seen in the short-horn humpless breeds native to West and Central African indiscriminate slaughter and an inattention to careful breeding that has put them on a path to extinction', Fall said . 'We must at the very least preserve these breeds either on the farm or in livestock genebanks because their genetic traits could be decisive in the fight against trypanosomosis, while their hardiness could be enormously valuable to farmers trying to adapt to climate change.'

Other African cattle breeds at risk include the Kuri cattle of southern Chad and northeastern Nigeria. The large bulbous-horned Kuri, in addition to being unfazed by insect bites, are excellent swimmers, having evolved in the Lake Chad region, and are ideally suited to wet conditions in very hot climates.

ILRI's push to preserve Africa's indigenous livestock is part of a broader effort to improve productivity on African farms through what is known as 'landscape genomics'. Landscape genomics involves, among other things, sequencing the genomes of different livestock varieties from many regions and looking for the genetic signatures associated with their suitability to a particular environment.

ILRI experts see landscape genomics as particularly important as climate change accelerates, requiring animal breeders to respond every more quickly and expertly to shifting conditions on the ground. But they caution that in Africa in particular the ability of farmers and herders to adapt to new climates depends directly on the continent's wealth of native livestock diversity.

'What we see too often is an effort to improve livestock productivity on African farms by supplanting indigenous breeds with imported animals that over the long-term will prove a poor match for local conditions and require a level of attention that is simply too costly for most smallholder farmers', said Carlos Seré, ILRI's Director General. 'What marginalized livestock-keeping communities need are investments in genetics and genomics that allow them to boost productivity with their African animals, which are best suited to their environments.'

Seré said new polices also are needed that encourage African pastoralist herders and smallholder farmers to continue maintaining their local breeds rather than abandoning them for imported animals. Such policies, he said, should include breeding programs that focus on improving the productivity of indigenous livestock as an alternative to importing animals.

Steve Kemp, who heads ILRI's genetics and genomics team, added that in addition to conservation on the farm, there must also be investments in preserving diversity by freezing sperm and embryos because farmers cannot be asked to forgo productivity increases solely in the name of diversity conservation.

'We cannot expect farmers to sacrifice their income just to preserve the future potential of diversity', Kemp said. 'We know that diversity is critical to dealing with the challenges that confront African farmers, but the valuable traits that may be important in the future are not always immediately obvious.'

Kemp called for a new approach to measuring the characteristics of livestock genetic resources. Today, he said, these estimates focus mainly on such things as the value of meat, milk, eggs and wool and do not include qualities that can be of equal or even greater importance to livestock keepers in Africa and other developing regions. These attributes include the ability of an animal to pull a plough, provide fertilizer, serve as a walking bank or savings account, and act as an effective form of insurance against crop loss.

But associating this wider array of attributes with an animal's DNA requires new ways of exploring and understanding livestock characteristics in a region where there is so much diversity in so many different environments.

'The tools are available to do this now, but we need the will, the imagination and the resources before it is too late', Kemp said.