Please find a corrected and revised statement below, along with a link to download revised maps here: http://ccafs.cgiar.org/resources/climate_hotspots. All edits to the original article posted on this blog are reflected in RED and BOLDFACE below.

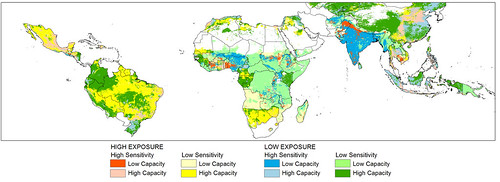

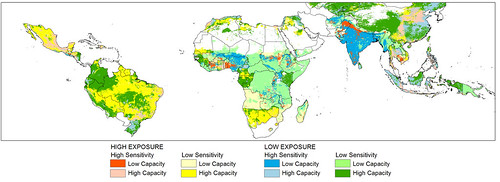

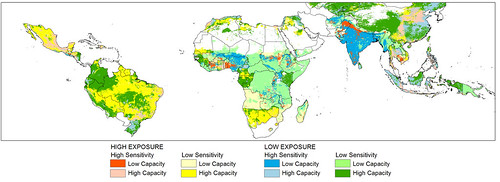

Five per cent reduction in crop season sensitivity to change capacity to cope: Corrected 13 Jul 2011 (map credit ILRI/CCAFS/Notenbaert).

A new study out today reveals future ‘hotspots’ of risk for hundreds of millions whose food problems are on a collision course with climate change. The scientists conducting the study warn that disaster looms for parts of Africa and all of India if chronic food insecurity converges with crop-wilting weather. They went on to say that Latin America is also vulnerable.

The red areas in the map above are food-insecure and intensively farmed regions that are highly exposed to a potential five per cent or greater reduction in the length of the growing season. Such a change over the next 40 years could significantly affect food yields and food access for 369 million people—many of them smallholder farmers—already living on the edge. This category includes almost all of India and significant parts of West Africa. While Latin America in general is viewed as having a ‘high capacity’ to cope with such shifts, there are millions of poor people living in this region who very dependent on local crop production to meet their nutritional needs (map credit: ILRI-CCAFS/Notenbaert).

This study matches future climate change ‘hotspots’ with regions already suffering chronic food problems to identify highly-vulnerable populations, chiefly in Africa and South Asia, but potentially in China and Latin America as well, where in fewer than 40 years, the prospect of shorter, hotter or drier growing seasons could imperil hundreds of millions of already-impoverished people.

The report, Mapping Hotspots of Climate Change and Food Insecurity in the Global Tropics, was produced by the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). The work was led by a team of scientists at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) responding to an urgent need to focus climate change adaptation efforts on people and places where the potential for harsher growing conditions poses the gravest threat to food production and food security.

The researchers pinpointed areas of intense vulnerability by examining a variety of climate models and indicators of food problems to create a series of detailed maps. One shows regions around the world at risk of crossing certain ‘climate thresholds’—such as temperatures too hot for maize or beans—that over the next 40 years could diminish food production. Another shows regions that may be sensitive to such climate shifts because in general they have large areas of land devoted to crop and livestock production. And finally, scientists produced maps of regions with a long history of food insecurity.

ILRI scientist Polly Ericksen, lead author of the hotspots study (photo credit: ILRI/MacMillan).

‘When you put these maps together they reveal places around the world where the arrival of stressful growing conditions could be especially disastrous,’ said Polly Ericksen, a senior scientist at ILRI, in Nairobi, Kenya and the study’s lead author. ‘These are areas highly exposed to climate shifts, where survival is strongly linked to the fate of regional crop and livestock yields, and where chronic food problems indicate that farmers are already struggling and they lack the capacity to adapt to new weather patterns.’

‘This is a very troubling combination,’ she added.

For example, in large parts of South Asia, including almost all of India, and parts of sub-Saharan Africa—chiefly West Africa—there are 265 million food-insecure people living in agriculture-intensive areas that are highly exposed to a potential five per cent decrease in the length of the growing period. Such a change over the next 40 years could significantly affect food yields and food access for people—many of them farmers themselves—already living on the edge.

Higher temperatures also could exact a heavy toll. Today, there are 170 million food-insecure and crop-dependent people in parts of West Africa, India and China who live in areas where, by the mid-2050s, maximum daily temperatures during the growing season could exceed 30 degrees Celsius (86 degrees Fahrenheit). This is close to the maximum temperature that beans can tolerate, while maize and rice yields may suffer when temperatures exceed this level. For example, a study last year in Nature found that even with optimal amounts of rain, African maize yields could decline by one percent for each day spent above 30ºC.

Regional predictions for shifts in temperatures and precipitation going out to 2050 were developed by analyzing the outputs of climate models rooted in the extensive data amassed by the Fourth Assessment Report (AR4) from the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Researchers identified populations as chronically food-insecure if more than 40 per cent of children under the age of five were ‘stunted’—that is, they fall well below the World Health Organization’s height-for-age standards.

CCAFS staff members Wiebke Foerch, based at ILRI, and Patti Kristjanson, based at the World Agroforestry Centre, hold discussions after ILRI’s Polly Ericksen presents her findings on poverty and climate change hotspots at the World Agroforestry Centre in May 2011 (photo credit: ILRI/MacMillan).

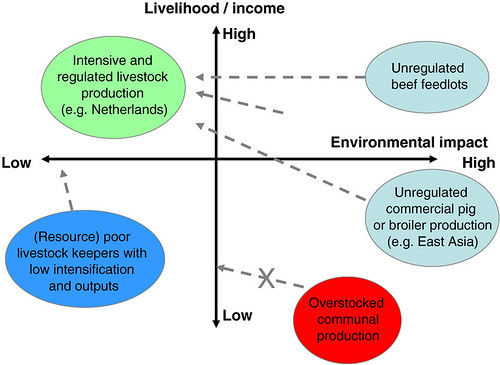

‘We are starting to see much more clearly where the effect of climate change on agriculture could intensify hunger and poverty, but only if we fail to pursue appropriate adaptation strategies,’ said Patti Kristjanson, a research theme leader at CCAFS and former agricultural economist at ILRI. ‘Farmers already adapt to variable weather patterns by changing their planting schedules or moving animals to different grazing areas. What this study suggests is that the speed of climate shifts and the magnitude of the changes required to adapt could be much greater. In some places, farmers might need to consider entirely new crops or new farming systems.’

Crop breeders at CGIAR centres around the world already are focused on developing so-called ‘climate ready’ crop varieties able to produce high yields in more stressful conditions. For some regions, however, that might not be a viable option—in parts of East and Southern Africa, for example, temperatures may become too hot to maintain maize as the staple crop, requiring a shift to other food crops, such as sorghum or cassava, to meet nutrition needs. In addition, farmers who now focus mainly on crop cultivation might need to integrate livestock and agroforestry as a way to maintain and increase food production.

Bruce Campbell, coordinator of the CGIAR program ‘Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS)’, based in Copenhagen, talks with guests at a seminar given about CCAFS by Andy Jarvis at ILRI’s Nairobi campus on 13 May 2011 (photo credit: ILRI/MacMillan).

‘International trade in agriculture commodities is also likely to assume even more importance for all regions as climate change intensifies the existing limits of national agriculture systems to satisfy domestic food needs,’ said Bruce Campbell, director of CCAFS. ‘We have already seen with the food price spikes of 2008 and 2010 that food security is an international phenomenon and climate change is almost certainly going to intensify that interdependence.’

Ericksen and her colleagues note that regions of concern extend beyond those found to be most at risk. For example, in many parts of Latin America, food security is relatively stable at the moment—suggesting that a certain amount of ‘coping capacity’ could be available to deal with future climate stresses that affect agriculture production. Yet there is cause for concern because millions of people in the region are highly dependent on local agricultural production to meet their food needs and they are living in the very crosshairs of climate change.

The researchers found, for example, that by 2050, prime growing conditions are likely to drop below 120 days per season in intensively-farmed regions of northeast Brazil and Mexico.

Growing seasons of at least 120 days are considered critical not only for the maturation of maize and several other staple food crops, but also for vegetation crucial to feeding livestock.

In addition, parts of Latin America are likely to experience temperatures too hot for bean production, a major food staple in the region.

Mario Herrero, another ILRI author of the study, with climate Polly Ericksen and CCAFS staff member Wiebke Forech, all based at ILRI’s Nairobi headquarters, wait to hear a presentation from visiting CCAFS scientist Andy Jarvis at ILRI on 13 May 2011 (photo credit: ILRI/MacMillan).

The study also shows that some areas today have a ‘low sensitivity’ to the effects of climate change only because there is not a lot of land devoted to crop and livestock production. But agriculture intensification would render them more vulnerable, adding a wrinkle, for example, to the massive effort under way to rapidly expand crop cultivation in the so-called ‘bread-basket’ areas of sub-Saharan Africa.

Philip Thornton (white shirt, facing camera), of ILRI and CCAFS, and other ILRI staff following a seminar on CCAFS given by Andy Jarvis at ILRI Nairobi on 13 May 2011 (photo credit: ILRI/MacMillan).

‘Evidence suggests that these specific regions in the tropics may be severely affected by 2050 in terms of their crop production and livestock capacity. The window of opportunity to develop innovative solutions that can effectively overcome these challenges is limited,’ said Philip Thornton, a CCAFS research theme leader and ILRI scientist and one of the paper’s co-authors. ‘Major adaptation efforts are needed now if we are to avoid serious food security and livelihood problems later.’

Areas where average maximum temperatures are expected to exceed 30⁰C by 2050, corrected version (map credit: ILRI-CCAFS/Notenbaert).

Read the whole report: Mapping hotspots of climate change and food insecurity in the global tropics, by Polly Ericksen, Philip Thornton, An Notenbaert, L Cramer, Peter Jones and Mario Herrero 2011. CCAFS Report no. 5 (final version). CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). Copenhagen, Denmark. Also available online at: www.ccafs.cgiar.org.

Click here for the CCAFS online media room with more materials, including corrected versions of the news release in English, Spanish, French and Chinese, and also versions of the two maps shown here in high resolution suitable for print media.

All the maps will be made available online later this year; for more information on the maps, please contact ILRI’s Polly Ericksen at p.ericksen [at] cgiar.org or CCAFS’ Vanessa Meadu at ccafs.comms [at] gmail.com.

Note: This study was led by scientists at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) for the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). CCAFS is a strategic partnership of the CGIAR and the Earth System Science Partnership (ESSP). CCAFS brings together the world’s best researchers in agricultural science, development research, climate science and Earth System science, to identify and address the most important interactions, synergies and tradeoffs between climate change, agriculture and food security. The CGIAR’s Lead Centre for the program is the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) in Cali, Colombia. For more information, visit www.ccafs.cgiar.org.