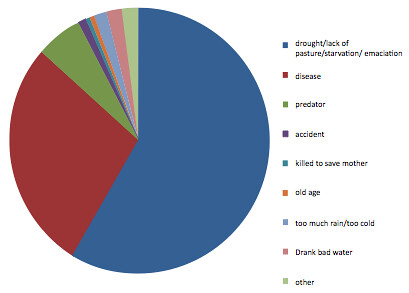

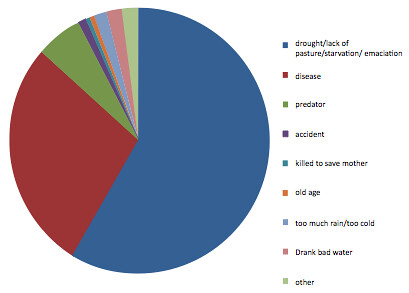

Causes of livestock deaths, figure reproduced in ILRI-AGRA book: Towards priority actions for market development for African farmers: Proceedings of an international conference, Nairobi, Kenya,13-15 May 2009. Nairobi (Source of figure: J McPeak, PI Little and C Doss. 2010. Livelihoods in a Risky Environment: Development and Change among East African Pastoralists, Routledge Press, London.)

With food shortages being predicted for dryland communities in both East and West Africa this year, it seems an appropriate time to revisit a major way African experts see that the continent can feed itself: Get Africa’s markets working.

Three years ago, 150 of the world’s leading market experts gathered in Nairobi, Kenya, to document the best ways to drive agricultural market development in sub-Saharan Africa. Both the proceedings of this international conference, Towards Priority Actions for Market Development for African Farmers, held 13–15 May 2009, and a synthesis of its outcomes, Priority Actions for Developing African Agricultural Markets, were published last year by ILRI and the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA).

The synthesis of this major African markets conference begins by referring to the sudden escalation in food costs that began in late 2010 and persisted into 2011—the second time in only three years that rapid food price rises, caused by a combination of production shortfalls and market failures causing dramatic gaps between supply and demand, rocked developing countries worldwide. With Africa’s long-term struggle with food insecurity, this continent and its economies and people are especially vulnerable to any sudden rise in food prices.

Even before the price shocks of 2008 and 2011, expert opinion had begun to coalesce on the centrality of agriculture in addressing African hunger and poverty. Much of the discussion has focused on increasing agricultural productivity through improved crop varieties and animal breeds, along with increased access to inputs and veterinary services, to boost farm yields. And, indeed, with crop and livestock yields on African farms typically a fraction of that in other regions, there appear to be big opportunities for new breadbaskets and milk sheds emerging across the continent.

But it will not be enough to simply produce more food from Africa’s fields and grazing lands. First, most Africans—including most smallholder, and even subsistence farmers—are net purchasers rather than growers of food. Also, as more and more people migrate from rural to urban areas, more and more Africans are relying on markets to meet their food needs. And because most rural as well as urban Africans spend a significant proportion of their income on food, even modest increases in food prices can tip millions of them into poverty.

Efficient and vibrant agricultural markets would help. But Africa’s agricultural markets suffer from a dearth of processing and storage facilities, pricing information, smallholder credit, and transport. These create inefficiencies that both raise prices for consumers and restrict sales opportunities for farmers, who are stopped from selling their food surpluses in nearby food-deficit regions.

View or download the full proceedings of this international conference:

Towards Priority Actions for Market Development for African Farmers, 13–15 May 2009, published by ILRI and AGRA, 2011.

and a synthesis of the outcomes of the conference:

Priority Actions for Developing African Agricultural Markets, published by ILRI and AGRA, 2011.

Five recommendations

The following five recommendations, highlighted here for their special pertinence to the drylands of East and West Africa, are presented in case studies published in the ILRI-AGRA markets book:

1 Support village seed trade in semi-arid areas

2 Manage pastoral risk with livestock insurance

3 Employ ICTs to raise smallholder income

4 Embrace informal agro-industry

5 Encourage intra-regional trade

Details of these recommendations follow.

1 Support village seed trade in semi-arid areas

Section 2 of the proceedings volume, Seed and Fertilizer Markets, includes a case study of the utility of Tapping the potential of village markets to supply seed in semi-arid Africa in Mali and Kenya. This paper, written by Melinda Smale, (Oxfam America), Latha Nagarajan, Lamissa Diakité, Patrick Audi (ICRISAT), Mikkel Grum (Bioversity International), Richard Jones (ICRISAT) and Eva Weltzien (ICRISAT), shows that village markets have the potential to supply high-quality pigeon pea and millet seed in semi-arid areas of Kenya and Mali, respectively.

The problem: Periods of seed insecurity occur in remote, semiarid areas when spatially covariate risk of drought is high and many farmers fall short of seed. In these remote environments, seed systems are typically informal, and farmers rely on each other for locally adapted varieties. They are not reliable clients for private seed companies because they purchase seed irregularly. Less improved germplasm has been developed for semiarid environments because of the high costs of breeding and supplying seed—a situation that has worsened with decreasing public funding for agricultural research. In the Mali study, village markets assure a supply of seed of identifiable, locally adapted, genetically diverse varieties as a final recourse in a risky environment where there are as yet no reliable formal channels, for which competitive varieties have not yet been bred, and the potential of agro-dealers to supply certified seed has not yet been exploited. In the Kenya study, well-adapted varieties have been bred, but no formalized channels of seed provision exist for pigeon pea and agro-dealers are active in selling improved varieties of maize and vegetables. In both studies, farm women are major seed trade actors. Interestingly, the characteristics of seed vendors and the locations of seed programs—not the price of seed—tend to determine the quantities of seed sold. The authors argue for strengthening and linking both formal and informal systems for non-hybrid dryland crops.

Some solutions: Several approaches piloted recently are potential candidates for improving the supply of good-quality seed on a large scale.

The West Africa Seed Alliance (WASA) and the Eastern and Southern Africa Seed Alliance (ESASA) work to help local entrepreneurs expand existing seed companies and create new ones.

Since private seed companies do not yet operate in the sorghum- and millet-based systems of the Sahel, where state agencies are underfunded, scientists at the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (lCRISAT) have tested several models that draw on the comparative advantages of farmer organizations.

2 Manage pastoral risk with livestock insurance

Section 3 of the ILRI-AGRA markets proceedings, Strengthening Finance, Insurance and Market Information, has two case studies of particular relevance to the food problems facing the drylands of West and East Africa.

First is a report on Insuring against drought-related livestock mortality: Piloting index-based livestock insurance in northern Kenya, written by ILRI’s Andrew Mude and his partners Sommarat Chantarat, Christopher Barrett, Michael Carter, Munenobu Ikegami and John McPeak.

The problem: Climate extremities pose the greatest risks to agricultural production, with droughts and floods not only causing crop failures but also forage and water scarcity that harms and kills livestock. The number of droughts and floods has risen sharply worldwide in the last decade, with disaster incidence in low-income countries rising at twice the global rate. In much of rural Africa, where water harvesting, irrigation and other similar water management methods are under developed, the impacts of climate change are expected to be especially pernicious.

A solution: In the last several years, new ways to manage weather-related agricultural risk have been developed. Of these, index-based insurance products represent a promising and exciting market-based option for managing climate-related risks faced by poor and remote populations.

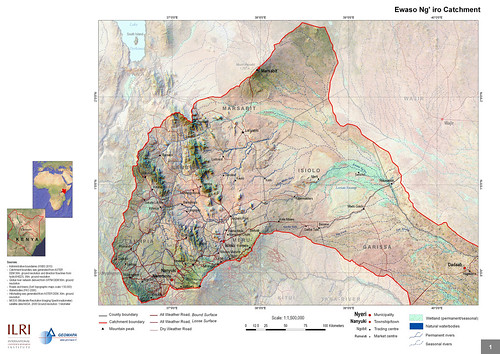

This paper describes research to design commercially viable index-based livestock insurance for pastoral populations of northern dryland Kenya, where the risk of drought and drought-related livestock deaths is high.

The analysis indicates a high likelihood of commercial sustainability in the target market and describes events leading up to the pilot launch in Marsabit District in early 2010. The paper concludes that this insurance tool has largely succeeded in helping Marsabit’s livestock herders better manage their risk of drought. Growing interest from both commercial and development partners is helping to take this instrument to other arid and semi-arid districts in Kenya and other countries and regions.

3 Employ ICTs to raise smallholder income

The same Section 3 of the ILRI-AGRA book offers a case study from West Africa, written by Kofi Debrah, coordinator of MISTOWA, supporting the Role of ICT-based management information systems in enhancing smallholder producers’ incomes.

The problem: Smallholder African farmers typically have little access to reliable marketing outlets in which to sell their surplus produce at remunerative prices. Furthermore, their ability to respond quickly to market opportunities is constrained by lack of labour, credit, market information and post-harvest facilities. As a result, West African farmer incomes from agriculture are low and variable and little agricultural produce is traded in the region.

A solution: A project funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), ‘Strengthening Regional Networks of Market Information Systems for Traders’ Organizations in West Africa’ (MISTOWA), helped build a private-public partnership to develop and deploy an ICT-based market information system that improved farmers’ access to markets. Some 12,500 agricultural producers and traders from 15 West African countries benefited from the project, with the beneficiaries reporting USD4,080 in benefits, or USD4.33 per dollar of donor funds invested.

Evidence from the beneficiaries suggests that access to real-time market information provides smallholder farmers with incentives for investing in agriculture.

4 Embrace informal agro-industry

Section 4 of the markets book, High-Value Commodities and Agroprocessing, includes a paper by ILRI scientists Amos Omore and Derek Baker on Integrating informal actors into the formal dairy industry in Kenya through training and certification.

The problem: Throughout the developing world, most food produced by smallholder farmers is delivered and processed by an ‘informal’ agro-industry, which is the principal source of food for most poor consumers and a major source of employment of poor people as traders and service providers. In spite of this, agro-industrial policy has historically tended to displace this informal sector with a formal one featuring relatively large-scale and capital-intensive production and marketing. Other policy concerns, such as public health and municipal planning, have further selected against informal agribusiness, particularly livestock’s informal agro-industry.

A solution: This paper presents a case study of interventions in the Kenyan informal milk industry that led to changes in dairy policy that in turn reduced poverty levels in the East African country. The paper identifies the informal agribusiness sector as fertile ground for alleviating poverty and supporting vulnerable groups.

Policies do well to embrace informal agro-industry, the research indicates, while helping it transform itself into a more formal industry.

The ILRI scientists show that the informal dairy industry can respond well to consumer demand for quality, particularly for safe food, and, when unjustified policy barriers are removed, can compete well when price alone becomes the basis of competition. These achievements support much conjecture in the development literature about the centrality of markets, and access to them, for pro-poor development and the idea that pro-poor markets rely heavily on policy and institutional change. The lessons of this project are being transferred to other informal commodity sectors (goats, beef cattle and pigs) in Africa and Asia and the policy changes seen in the Kenya dairy project have been adopted across the East African region.

5 Encourage intra-regional trade

Section 6 of the markets book, Encouraging Regional Trade, includes a paper on The impact of non-tariff barriers on maize and beef trade in East Africa. The paper is written by Joseph Karugia (ILRI and ReSAKSS-ECA), Julliet Wanjiku (ILRI and ReSAKSS-ECA), Jonathan Nzuma, Sika Gbegbelegbe, Eric Macharia, Stella Massawe, Ade Freeman, Michael Waithaka and Simeon Kaitibie.

The problem: In 2004, the East African Community member states established an East African Community Customs Union, committing them, among other things, to eliminate non-tariff barriers to facilitate increased trade and investment flows between member states and to create a large market for East African people. However, several such trade barriers are still applied by member states and there exists little reliable information about how, and how much, these non-tariff barriers are actually hurting regional trade. This study identified the existing non-tariff barriers on the trade of maize and beef in East Africa and quantified their impacts on trade and citizen welfare in the region. The study found that the main types of non-tariff barriers within the three founding members of the East African Community (Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda) are similar and include administrative requirements, taxes/duties, roadblocks, customs barriers, weighbridges, licensing, corruption and transiting.

Some solutions: The study recommends taking a regional approach to exploit economies of scale by eliminating non-tariff barriers, since they are similar across the member countries and across commodities. Specific policy recommendations include streamlining administrative procedures at border points to improve efficiency; speeding up implementation of procedures at point of origin and at the border points; and implementing monitoring systems to provide feedback to relevant authorities on progress in removing unnecessary barriers to trade within East and Central Africa. The welfare analysis of the study shows that abolishment or reduction of the existing non-tariff barriers in maize and beef trade increases trade flows of maize and beef within the East African Community, with Kenya importing more maize from both Uganda and Tanzania and Uganda exporting more beef to Kenya and Tanzania. As a result, positive net welfare gains are attained for the entire East African Community maize and beef sub-sectors.

These findings give compelling evidence in support of the elimination of non-tariff barriers within the East African Community Customs Union.