ILRI’s Bruce Scott and Andrew Mude (right) discuss ILRI’s use of open data with Kenyan President Mwai Kibaki (centre), Minister for Information and Communication Samuel Pogishio (centre left), Permanent Secretary Ministry of Information and Communication Bitange Ndemo (centre right), and other dignitaries when they visited ILRI’s booth at the launch of the Kenya Government’s ‘Open Data Web Portal’ on 8 Jul 2011 in Nairobi (photo credit: ILRI/Njiru).

An ‘Index-Based Livestock Insurance’ project led by the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) was today (8 July 2011) highlighted as one of the successful, innovative and technology-driven initiatives using open data to create solutions that contribute towards helping Kenya achieve its long-term national development plan.

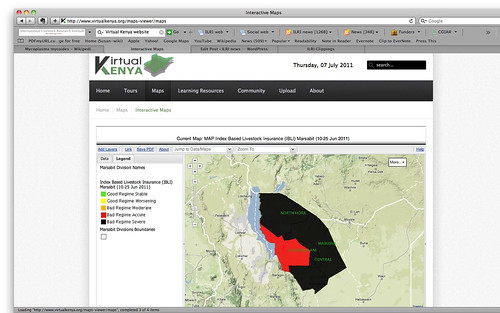

Speaking during the presidential launch of the ‘Kenya Government Open Data Web portal’ at Nairobi’s Kenyatta International Conference Centre, Andrew Mude, a scientist with ILRI who leads the Index-Based Livestock Insurance project, described how the project has developed an insurance model for pastoralist livestock keepers using open data. The project uses satellite-based readings of forage cover to find out how much fodder is available for livestock in northern Kenya and the data is combined with livestock mortality data from the Kenya Arid Lands Management project to predict livestock deaths against which livestock herders can insure themselves.

‘This model allows us to predict the current state of livestock mortality in northern Kenya. It currently shows there is a high livestock mortality rate in Marsabit District, which means that insurance may be paid to pastoralists this year,’ said Mude. Marsabit District, in Kenya’s northern drylands, is currently facing a severe drought that is also affecting Somalia and southern Ethiopia, in the Horn of Africa.

Stared in January 2010, the Index-Based Livestock Insurance project is insuring over 2600 households in Marsabit, which is helping livestock keepers there to sustain their livelihoods. The project is supported by the World Bank, the UK Department for International Development and the United States Agency for International Development, among other donors. It has received considerable support from the Kenya Government and recently received the Vision 2030 ICT award for ‘solutions that drive economic development as outlined in Kenya’s Vision 2030.’

Kenya President Mwai Kibaki officially opened the Kenya Government Open Data portal. He said the new open data platform would allow policymakers and researchers to find timely information to guide-decision making. ‘This launch is an important step towards ensuring government information is made readily available to Kenyans and will allow citizens to track the delivery of services,’ Kibaki said.

The new Kenya Government Open Data Web portal will make available to the public several large government datasets, including information on population, education, healthcare and government spending in an easy to search and view format. The portal will allow Kenyans to search and display national and county-level data in graphs and maps for easy comparison and analysis of information.

The launch brought together government officials, policymakers and ICT-sector players who are using open data to build applications that take information closer to Kenyans. Among today’s presentations was the National Council for Law Reporting Kenya Law Reports website, which is making available to the public for the first time the Kenya Gazette (from 1899 to 2011) and all of Kenya’s parliamentary proceedings since 1960.

‘Open data leads to open knowledge, which leads to open solutions and open development,’ said Johannes Zutt, World Bank Country Director for Kenya, who shared lessons from the World Bank’s experience and said open data can ‘fuel innovation in Kenya’s technology sector.’

‘This is a turning point in Kenya’s history,’ said Bruce Scott, ILRI’s director of Partnerships and Communications. ‘Kenya is among the first African countries that have made available this kind of information to their citizens online; this will empower its people in line with the country’s new constitution. ILRI is happy to be associated with this event.’

For more information about IBLI see the following.

ILRI news articles

/archives/5000

/archives/3180

Short video

http://blip.tv/ilri/development-of-the-world-s-first-insurance-for-african-pastoralist-herders-3776231

To read more about the Kenya Open Data portal, visit their website:

http://www.opendata.go.ke