Next week, staff of the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) and many other CGIAR centres and research programs are attending the 6th Africa Agriculture Science Week (AASW6), which is being hosted by the Forum for Agricultural Research in Africa (FARA) and the Government of Ghana and runs from Monday–Saturday, 15–20 Jul 2013.

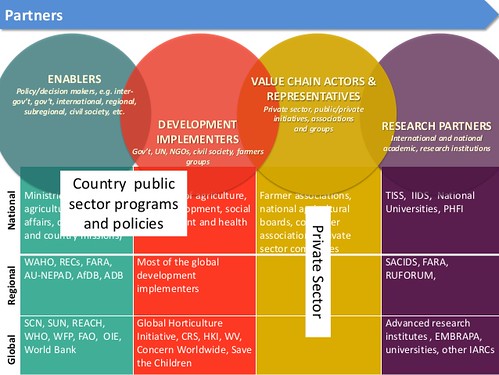

CGIAR is a global partnership for a food-secure future that conducts and disseminates research to improve the lives, livelihoods and lands of the world’s poorest people. CGIAR research is conducted by 15 of the world’s leading agricultural development research centres and 16 global research programs, all of them partnering with many stakeholders in Africa. More than half of CGIAR funding (52% in 2012) targets African-focused research.

The theme of next week’s AASW6 is ‘Africa Feeding Africa through Agricultural Science and Innovation’. CGIAR is supporting African-driven solutions to food security by partnering with FARA and the African Union, the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP), sub-regional organizations, national agricultural research systems and many other private and non-governmental as well as public organizations.

ILRI and livestock issues at AASW6

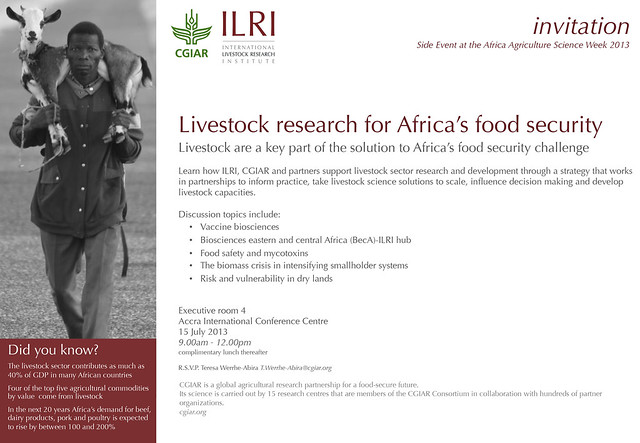

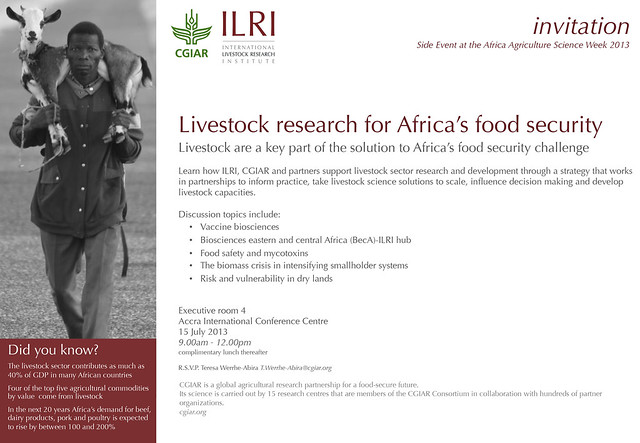

Ten ILRI scientists and staff will briefly speak and then engage with other participants in a side event ILRI is organizing at AASW6 on the topic of Livestock research for Africa’s food security. This three-hour morning side event will be facilitated by ILRI’s knowledge management and communication specialist, Ewen Le Borgne, and will be highly participatory in nature.

If you plan to attend this session, please shoot an email confirmation to Teresa Werrhe-Abira(t.werrhe-abira [at] cgiar.org) so we can organize refreshments.

And if you’d like to use this opportunity to talk with or interview one of the ILRI staff members below, or just meet them, please do so! ILRI communication officers Muthoni Njiru (m.njiru [at] cgiar.org) and Paul Karaimu (p.karaimu [at] cgiar.org) will be on hand at the ILRI side session (and you’ll find one or both at the CGIAR booth most of the rest of the week) to give you any assistance you may need.

Among the speakers at the ILRI side session will be the following.

Jimmy Smith, a Canadian, became director general of ILRI in Oct 2011. Before that, he worked for the World Bank in Washington, DC, leading the Bank’s Global Livestock Portfolio. Before joining the World Bank, Smith held senior positions at the Canadian International Development Agency. Still earlier in his career, he worked at ILRI and its predecessor, the International Livestock Centre for Africa (ILCA), where he served as the institute’s regional representative for West Africa and subsequently managed the ILRI-led Systemwide Livestock Programme of the CGIAR, involving ten CGIAR centres working at the crop-livestock interface. Before his decade of work at ILCA/ILRI, Smith held senior positions in the Caribbean Agricultural Research and Development Institute (CARDI). Smith is a graduate of the University of Illinois at Urban-Champaign, USA, where he completed a PhD in animal sciences. He was born in Guyana, where he was raised on a small mixed crop-and-livestock farm.

John McIntire (USA) is ILRI deputy director general for research-integrated sciences. He obtained a PhD in agricultural economics in 1980 from Tufts University using results of farm-level field studies of smallholder crop production in francophone Africa. He subsequently served as an economist for the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), in Washington, DC, and the West Africa Program of the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT), in Burkina Faso and Niger, and the International Livestock Centre for Africa (ILCA), one of ILRI’s two predecessors, in Ethiopia. He is co-author of Crop Livestock Integration in Sub-Saharan Africa (1992), a book still widely cited 20 years later. McIntire joined the World Bank in 1989, where he worked (in Mexico, Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal, The Gambia, Cape Verde, Guinea, Tanzania, Uganda and Burundi) until his retirement in 2011. In 2011, he became the second person to receive both the Bank’s ‘Good Manager Award’ and ‘Green Award for Environmental Leadership’.

Shirley Tarawali (UK) is ILRI director of institutional planning and partnerships. Before taking on this role, Tarawali was director of ILRI’s People, Livestock and the Environment Theme, with responsibilities spanning sub-Saharan Africa and Asia. She holds a PhD in plant science from the University of London. Previously, Tarawali held a joint appointment with ILRI and the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA), based in Ibadan, Nigeria. Her fields of specialization include mixed crop-livestock and pastoral systems in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia.

-

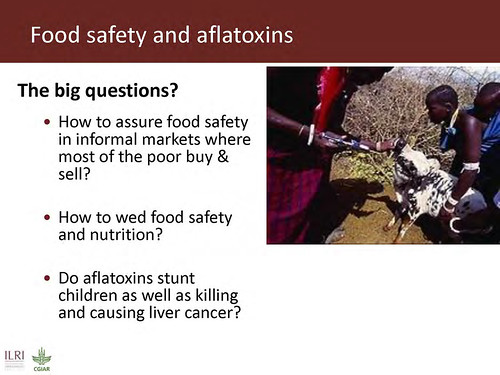

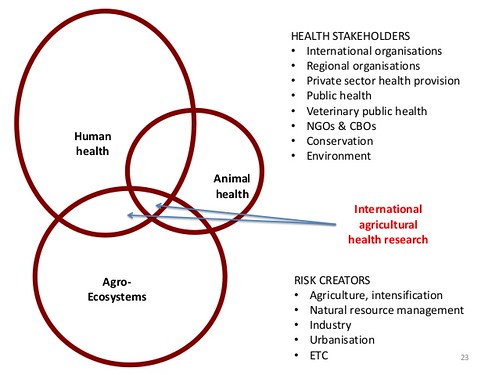

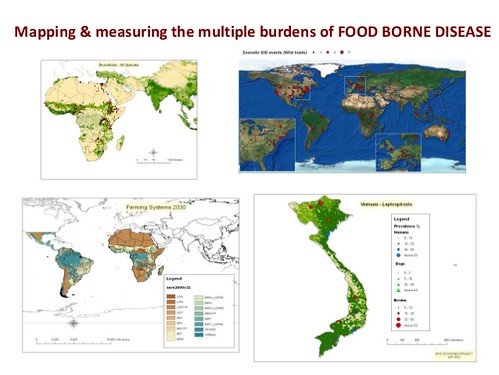

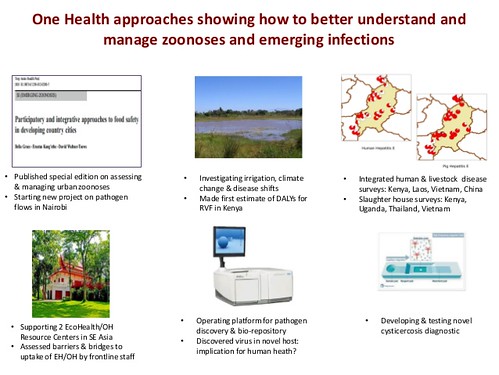

Delia Grace: Food safety and aflatoxins

Delia Grace (Ireland) is an ILRI veterinarian and epidemiologist who leads a program at ILRI on food safety and zoonosis. She also leads a flagship project on ‘Agriculture-Associated Diseases’, which is a component of the CGIAR Research Program on Agriculture for Nutrition and Health, led by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), USA. Grace has broad developing-country expertise in food safety, risk factor analysis, ecohealth/one health, gender and livestock, participatory methods, randomized trials and health metrics.

Questions Grace will address in ILRI’s side event are:

What are risk-based approaches to food safety in informal markets where most of the poor buy & sell?

How should we deal with food safety dynamics: livestock revolution, urbanization, globalization?

How can we better understand the public health impacts of aflatoxins?

-

Polly Ericksen: Vulnerability and risk in drylands

Polly Ericksen (USA) leads drylands research at ILRI and for the CGIAR Research Program on Drylands Systems in East and Southern Africa, where, in the coming years, the program aims to assist 20 million people and mitigate land degradation over some 600,000 square kilometres. That CGIAR research program as a whole is led by the International Centre for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), Syria. Ericksen also leads a Technical Consortium for Ending Drought Emergencies and Building Resilience to Drought in the Horn of Africa. Her broad expertise includes food systems, ecosystem services and adaptations to climate change by poor agricultural and pastoral societies.

Questions Ericksen will address in ILRI’s side event are:

How can commercial pastoral livestock production lead to growth in risk-prone drylands?

Is there a long-term role for livestock insurance in pastoral production systems?

-

Iain Wright, Alan Duncan and Michael Blümmel: The biomass crisis in intensifying smallholder systems

Iain Wright (UK) is ILRI director general’s representative in Ethiopia and head of ILRI’s Addis Ababa campus, where over 300 staff are located. He also directs ILRI’s Animal Science for Sustainable Productivity program, a USD15-million global program working to increase the productivity of livestock systems in developing countries through high-quality animal science (breeding, nutrition and animal health) and livestock systems research. Before this, Wright served as director of ILRI’s People, Livestock and the Environment theme. And before that, from 2006 to 2011, he was ILRI’s regional representative for Asia, based in New Delhi and coordinating ILRI’s activities in South, Southeast Asia and East Asia. Wright has a PhD in animal nutrition. Before joining ILRI, he managed several research programs at the Macaulay Institute, in Scotland.

Alan Duncan (UK) is an ILRI livestock feed specialist and joint leader of the Nile Basin Development Challenge Programme. Duncan joined ILRI in 2007, also coming from Scotland’s Macaulay Institute. Duncan has a technical background in livestock nutrition but in recent years has been researching institutional barriers to feed improvement among smallholders. He also works on livestock-water interactions, which are a key issue in Ethiopia, where he is based, particularly in relation to the competition for water occurring between the growing of livestock feed and that of staple crops. Duncan manages a range of research-for-development projects and acts as ILRI’s focal point for the CGIAR Research Program on Integrated Systems for the Humid Tropics, which is led by the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA), Nigeria.

Michael Blümmel (Germany) is an ILRI animal nutritionist with PhD (1994) and Habilitation (2004) degrees from the University of Hohenheim, in Germany. He has more than 20 years of experience in research, teaching and development in Europe, the US, Africa and Asia. Blümmel’s major research interests include feeding and feed resourcing at the interface of positive and negative effects from livestock, multi-dimensional crop improvement concomitantly to improve food, feed and fodder traits in new crop cultivars, and optimization of locally available feed resources through small business enterprises around decentralized feed processing.

A question they will address in ILRI’s side event is:

What are the options for sustainable intensification through livestock feeding?

-

Ethel Makila: Mobilizing biosciences for a food-secure Africa

Ethel Makila (Kenya) is ILRI communications officer for the Biosciences eastern and Central Africa-ILRI Hub. She is a graphic designer expert in development communication, media and education. At the BecA-ILRI Hub, she is responsible for increasing awareness of the Hub’s activities, facilities and impacts among African farmers, research institutes, government departments, Pan-African organizations and the international donor and research communities.

Questions Makila will address in ILRI’s side event are:

How can we build bio-sciences capacity in Africa to move from research results to development impacts?

How can we keep the BecA-ILRI Hub relevant to the research needs and context of African scientists?

-

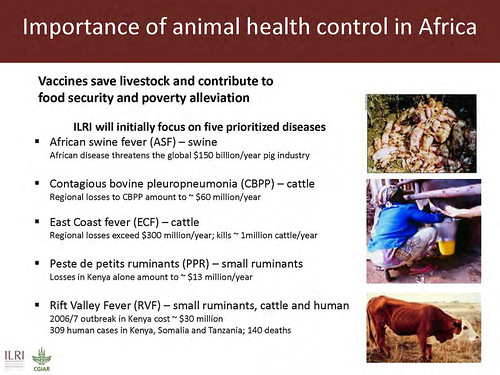

Suzanne Bertrand: Vaccine biosciences

Suzanne Bertrand (Canada) is ILRI deputy director general for research-biosciences. With a PhD in plant molecular biology from Laval University, Bertrand began her career as a scientist with Agri-Food Canada, working on forage plants. Her focus shifted rapidly from laboratory-based research to application of modern agri-technology in the developing world. Her overseas assignments included spells in the People’s Republic of China and Tunisia. She spent six years in the USA, first as research assistant professor at North Carolina State University, and then as a founding principal for a biotechnology start-up company. She then joined Livestock Improvement (LIC), a large dairy breeding enterprise in New Zealand, where she managed LIC’s Research and Development Group, delivering science-based solutions in the areas of genomics, reproductive health, animal evaluation and commercialization to the dairy sector. In 2008, Bertrand became director, International Linkages for the Ministry of Research, Science and Technology in New Zealand. She was later chief executive officer for NZBIO, an NGO representing the interests and supporting growth of the bioscience sector in New Zealand.

Questions Bertrand will address in ILRI’s side event are:

How do we stimulate and sustain an African vaccine R&D pathway to achieve impact?

How can we grow a biotech and vaccine manufacturing sector in Africa?

Find more information about AASW6, including a full agenda, and follow the hashtag #AASW6 on social media.

Full list of ILRI participants at AASW6

-

Jimmy Smith, director general, based at ILRI’s headquarters, in Nairobi, Kenya

-

John McIntire, deputy director general-Integrated Sciences, Nairobi

-

Suzanne Bertrand, deputy director general—Biosciences, Nairobi

-

Shirley Tarawali, director of Institutional Planning and Partnerships, Nairobi

-

Iain Wright, director of ILRI Animal Sciences for Sustainable Agriculture Program, based at ILRI’s second principal campus, in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

-

Abdou Fall, ILRI regional representative and manager of conservation of West African livestock genetic resources project, based in Senegal

-

Iheanacho (Acho) Okike, manages project of the CGIAR Research Program on Livestock and Fish, based in Ibadan, Nigeria

-

Appolinaire Djikeng, director of the Biosciences eastern and Central Africa-ILRI Hub, Nairobi

-

Iddo Dror, head of ILRI Capacity Development, Nairobi

-

Delia Grace, leads ILRI Food Safety and Zoonosis program and also an ‘Agriculture-Associate Diseases’ component of CRP on Agriculture for Nutrition and Health, Nairobi

-

Joy Appiah, former student in ILRI Safe Food, Fair Food project; ILRI is supporting his participation at AASW6; he is now at the University of Ghana

-

Polly Ericksen, leads dryands research within ILRI Livestock Systems and Environment program, serves as ILRI focal point for two CGIAR research programs—on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security and Dryland Systems—and leads a Technical Consortium for Building Resilience to Drought in the Horn of Africa, based in Nairobi

-

Katie Downie, coordinator of the Technical Consortium for Building Resilience to Drought in the Horn of AfricaHorn of Africa, Nairobi

-

Alan Duncan, leads feed innovations research within ILRI Animal Sciences for Sustainable Agriculture program and serves as ILRI focal point for the CGIAR Research Program on the HumidTropics, Addis Ababa

-

Michael Blümmel, leads feed resources research within ILRI Animal Sciences for Sustainable Agriculture program, based at ICRISAT, in Hyderabad, India

-

Allan Liavoga, deputy program manager of Bio-Innovate, Nairobi

-

Dolapo Enahoro, agricultural economist within ILRI Policy, Trade and Value Chains program, based in Accra

Communications support

-

Ewen LeBorgne, ILRI knowledge management and communications specialist; is facilitating ILRI’s side session at AASW6 on 15 Jul; based in Addis Ababa

- Muthoni Njiru, ILRI communications officer in ILRI Public Awareness unit: overseeing media relations, exhibit materials, video reporting at AASW6; Nairobi

- Paul Karaimu, ILRI communications writer/editor in ILRI Public Awareness unit: overseeing blogging, photography, video reporting at AASW6; Nairobi

- Ethel Makila, ILRI communications specialist for the BecA-ILRI Hub, Nairobi

- Albert Mwangi, ILRI communications specialist for Bio-Innovate, Nairobi

plus

- Cheikh Ly, ILRI board member, from Senegal, veterinary expert at FAO, based in Accra, Ghana

-

Lindiwe Majele Sibanda, ILRI board chair, from Zimbabwe, livestock scientist, agricultural policy thinker, and CEO and head of mission of the Food, Agriculture and Natural Resources Policy Analysis Network (FANRPAN), based in Pretoria, South Africa