Here, for your New Year’s reading/viewing pleasure, are 20 slide presentations on 12 topics made by staff of the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) in 2012 that we missed reporting on here (at the ILRI News Blog) during the year.

Happy reading and Happy New Year!

1 LIVESTOCK RESEARCH FOR FOR DEVELOPMENT

>>> Sustainable and Productive Farming Systems: The Livestock Sector

Jimmy Smith

International Conference on Food Security in Africa: Bridging Research and Practice, Sydney, Australia

29-30 Nov 2012; posted on ILRI Slideshare 27 Nov 2012; 426 views.

Excerpts:

A balanced diet for 9 billion: Importance of livestock

• Enough food: much of the world’s meat, milk and cereals comes from developing-country livestock based systems

• Wholesome food: Small amounts of livestock products – huge impact on cognitive development, immunity and well being

• Livelihoods: 80% of the poor in Africa keep livestock, which contribute at least one-third of the annual income.

The role of women in raising animals, processing and 3 selling their products is essential.

Key messages: opportunities

• Livestock for nutrition and food security:

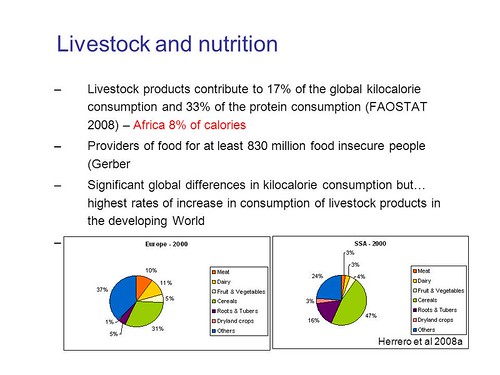

– Direct – 17% global kilocalories; 33% protein; contribute food for 830 million food insecure.

Demand for all livestock products will rise by more than 100% in the next 30 years, poultry especially so (170% in Africa)

– Indirect – livelihoods for almost 1 billion, two thirds women

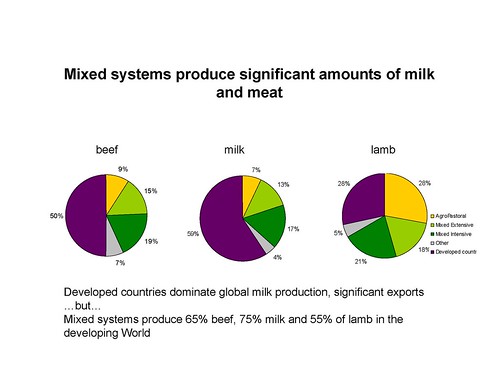

• Small-scale crop livestock systems (less than 2ha; 2 TLU) provide 50–75% total livestock and staple food production in Africa and Asia

and provide the greatest opportunity for research to impact on a trajectory of growth that is inclusive –

equitable, economically and environmentally sustainable.

>>> The Global Livestock Agenda: Opportunities and Challenges

Jimmy Smith

15th AAAP [Asian-Australasian Association of Animal Production] Animal Science Congress, Bangkok,Thailand

26–30 Nov 2012; posted on ILRI Slideshare 27 Nov 2012; 1,650 views

Excerpt:

Livestock and global development challenges

• Feeding the world

– Livestock provide 58 million tonnes of protein annually and 17% of the global kilocalories.

• Removing poverty

– Almost 1 billion people rely on livestock for livelihoods

• Managing the environment

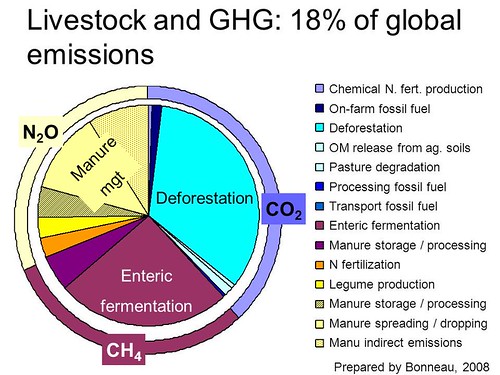

– Livestock contribute 14–18% anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, use 30% of the freshwater used for agriculture and 30% of the ice free land

– Transition of livestock systems

– Huge opportunity to impact on future environment

• Improving human health

– Zoonoses and contaminated animal-source foods

– Malnutrition and obesity

>>> Meat and Veg: Livestock and Vegetable Researchers Are Natural,

High-value, Partners in Work for the Well-being of the World’s Poor

Jimmy Smith

World Vegetable Center, Taiwan

18 Nov 2012; posted on ILRI Slideshare 27 Nov 2012; 294 views.

Excerpts:

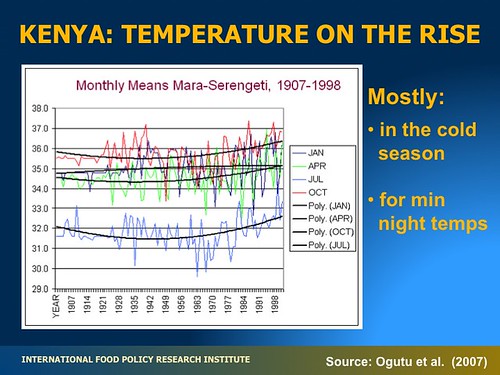

Livestock and vegetables suit an urbanizing, warming world

Smallholder livestock and vegetable production offers similar opportunities:

• Nutritious foods for the malnourished.

• Market opportunities to meet high urban demand.

• Income opportunities for women and youth.

• Expands household incomes.

• Generates jobs.

• Makes use of organic urban waste and wastewater.

• Can be considered ‘organic’ and supplied to niche markets.

Opportunities for livestock & vegetable research

Research is needed on:

• Ways to manage the perishable nature of these products.

• Innovative technological and institutional solutions for food safety and public health problems that suit developing countries.

• Processes, regulations and institutional arrangements regarding use of banned or inappropriate pesticides,

polluted water or wastewater for irrigation, and untreated sewage sludge for fertilizer.

• Innovative mechanisms that will ensure access by the poor to these growing markets.

• Ways to include small-scale producers in markets demanding

increasingly stringent food quality, safety and uniformity standards.

>>> The African Livestock Sector:

A Research View of Priorities and Strategies

Jimmy Smith

6th Meeting of the CGIAR Independent Science and Partnership Council, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

26−29 Sep 2012; posted on ILRI Slideshare 25 Sep 2012; 4,227 views.

Excerpts:

Livestock for nutrition

• In developing countries, livestock contribute 6−36% of protein and 2−12% of calories.

• Livestock provide food for at least 830 million food-insecure people.

• Small amounts of animal-source foods have large benefits on child growth and cognition and on pregnancy outcomes.

• A small number of countries bear most of the burden of malnutrition (India, Ethiopia, Nigeria−36% burden).

Smallholder competitiveness

Ruminant production

• Underused local feed resources and family labour give small-scale ruminant producers a comparative advantage over larger producers, who buy these.

Dairy production

• Above-normal profits of 19−28% of revenue are found in three levels of intensification of dairy production systems.

• Non-market benefits – finance, insurance, manure, traction – add 16−21% on top of cash revenue.

• Dairy production across sites in Asia, Africa, South America showed few economies of scale until opportunity costs of labour rose.

• Nos. of African smallholders still growing strongly.

Small ruminant production

• Production still dominated by poor rural livestock keepers, incl. women.

• Peri-urban fattening adds value.

>>> The CGIAR Research Program on Livestock and Fish and its Synergies

with the CGIAR Research Program on Agriculture for Nutrition and Health

Delia Grace and Tom Randolph

Third annual conference on Agricultural Research for Development: Innovations and Incentives, Uppsala, Sweden

26–27 Sep 2012; posted on ILRI Slideshare 13 Oct 2012; 468 views.

Excerpts:

Lessons around innovations and incentives

• FAILURE IS GETTING EASIER TO PREDICT – but not necessarily success

• INNOVATIONS ARE THE LEVER – but often succeed in the project context but not in the real world

• PICKING WINNERS IS WISE BUT PORTFOLIO SHOULD BE WIDER– strong markets and growing sectors drive uptake

• INCENTIVES ARE CENTRAL: value chain actors need to capture visible benefits

• POLICY: not creating enabling policy so much as stopping the dead hand of disabling policy and predatory policy implementers

‘Think like a systemicist, act like a reductionist.’

>>> The Production and Consumption of Livestock Products

in Developing Countries: Issues Facing the World’s Poor

Nancy Johnson, Jimmy Smith, Mario Herrero, Shirley Tarawali, Susan MacMillan, and Delia Grace

Farm Animal Integrated Research 2012 Conference, Washington DC, USA

4–6 Mar 2012; posted on ILRI Slideshare 7 Mar 2012; 1,108 views.

Excerpts:

The rising demand for livestock foods in poor countries presents

– Opportunities

• Pathway out of poverty and malnutrition

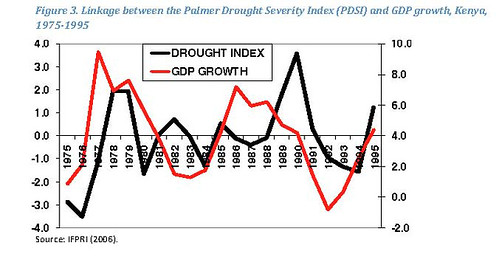

• Less vulnerability in drylands

• Sustainable mixed systems

– Threats

• Environmental degradation at local and global scales

• Greater risk of disease and poor health

• Greater risk of conflict and inequity

• Key issues for decision makers

– appreciation of the vast divide in livestock production between rich and poor countries

– intimate understanding of the specific local context for specific livestock value chains

– reliable evidence-based assessments of the hard trade-offs involved in adopting any given approach to livestock development

• Institutional innovations as important as technological/biological innovations in charting the best ways forward

– Organization within the sector

– Managing trade offs at multiple scales

2 LIVESTOCK FEEDS

>>> Livestock feeds in the CGIAR Research Programs

Alan Duncan

Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO) West Africa Regional Workshop on Crop Residues, Dakar, Senegal

10–13 Dec 2012; posted on ILRI Slideshare on 18 Dec 2012; 3,437 views.

>>> Biomass Pressures in Mixed Farms: Implications for Livelihoods

and Ecosystems Services in South Asia & Sub-Saharan Africa

Diego Valbuena, Olaf Erenstein, Sabine Homann-Kee Tui, Tahirou Abdoulaye, Alan Duncan, Bruno Gérard, and Nils Teufel

Planet Under Pressure Conference, London, UK

26-29 Mar 2012; posted on ILRI Slideshare 27 Mar 2012; 1,999 views.

3 LIVESTOCK IN INDIA

>>> Assessing the Potential to Change Partners’ Knowledge,

Attitude and Practices on Sustainable Livestock Husbandry in India

Sapna Jarial, Harrison Rware, Pamela Pali, Jane Poole and V Padmakumar

International Symposium on Agricultural Communication and

Sustainable Rural Development, Pantnagar, Uttarkhand, India

22–24 Nov 2012; posted on ILRI Slideshare 30 Nov 2012; 516 views.

Excerpt:

Introduction to ELKS

• ‘Enhancing Livelihoods Through Livestock Knowledge Systems’ (ELKS) is an initiative

to put the accumulated knowledge of advanced livestock research directly to use

by disadvantaged livestock rearing communities in rural India.

• ELKS provides research support to Sir Ratan Tata Trust and its development partners

to address technological, institutional and policy gaps.

4 AGRICULTURAL R4D IN THE HORN OF AFRICA

>>> Introducing the Technical Consortium

for Building Resilience to Drought in the Horn of Africa

Polly Ericksen, Mohamed Manssouri and Katie Downie

Global Alliance on Drought Resilience and Growth, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

5 Nov 2012; posted on ILRI Slideshare 21 Dec 2012; 8,003 views.

Excerpts:

What is the Technical Consortium?

• A joint CGIAR-FAO [Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations] initiative,

with ILRI representing the CGIAR Centres and the FAO Investment Centre representing FAO.

• ILRI hosts the Coordinator on behalf of the CGIAR.

• Funded initially by USAID [United State Agency for International Development] for 18 months –

this is envisioned as a longer term initiative, complementing the implementation of investment plans

in the region and harnessing, developing and applying innovation and research to enhance resilience.

• An innovative partnersh–ip linking demand-driven research sustainable action for development.

What is the purpose of the Technical Consortium?

• To provide technical and analytical support to IGAD [Inter-governmental Authority on Development]

and its member countries to design and implement the CPPs [Country Programming Papers]

and the RPF [Regional Programming Framework], within the scope of

the IGAD Drought Disaster Resilience and Sustainability Initiative (IDDRSI).

• To provide support to IGAD and its member countries to develop regional and national

resilience-enhancing investment programmes for the long term development of ASALs [arid and semi-arid lands].

• To harness CGIAR research, FAO and others’ knowledge on drought resilience and bring it to bear on investments and policies.

5 LIVESTOCK AND FOOD/NUTRITIONAL SECURITY

>>> Mobilizing AR4D Partnerships to Improve

Access to Critical Animal-source Foods

Tom Randolph

Pre-conference meeting of the second Global Conference for Agricultural Research for Development (GCARD2), Punta de Este, Uruguay

27 Oct 2012; posted on ILRI Slideshare 29 Oct 2012; 385 views.

Excerpts:

The challenge

• Can research accelerate livestock and aquaculture development to benefit the poor?

– Mixed record to date

– Systematic under-investment

– Also related to our research-for-development model?

• Focus of new CGIAR Research Program

– Increase productivity of small-scale systems

> ‘by the poor’ for poverty reduction

> ‘for the poor’ for food security

Correcting perceptions

1. Animal-source foods are a luxury and bad for health, so should not promote

2. Small-scale production and marketing systems are disappearing; sector is quickly industrializing

3. Livestock and aquaculture development will have negative environmental impacts

Our underlying hypothesis

• Livestock and Blue Revolutions: accelerating demand in developing countries as urbanization and incomes rise

• Industrial systems will provide a large part of the needed increase in supply to cities and the better-off in some places

• But the poor will often continue to rely on small-scale production and marketing systems

• If able to respond, they could contribute, both increasing supplies and reducing poverty

. . . and better manage the transition for many smallholder households.

6 LIVESTOCK INSURANCE

>>> Index-Based Livestock Insurance:

Protecting Pastoralists against Drought-related Livestock Mortality

Andrew Mude

World Food Prize ‘Feed the Future’ event, Des Moines, USA

18 Oct 2012; posted on ILRI Slideshare 22 Oct 2012; 576 views.

Excerpts:

Index-Based Livestock Insurance

• An innovative insurance scheme designed to protect pastoralists against the risk of drought-related livestock deaths

• Based on satellite data on forage availability (NDVI), this insurance pays out when forage scarcity is predicted to cause livestock deaths in an area.

• IBLI pilot first launched in northern Kenya in Jan 2010. Sold commercially by local insurance company UAP with reinsurance from Swiss Re

• Ethiopia pilot launched in Aug 2012.

Why IBLI? Social and Economic Welfare Potential

An effective IBLI program can:

• Prevent downward slide of vulnerable populations

• Stabilize expectations & crowd-in investment by the poor

• Induce financial deepening by crowding-in credit S & D

• Reinforce existing social insurance mechanisms

Determinants of IBLI Success

DEMONSTRATE WELFARE IMPACTS

• 33% drop in households employing hunger strategies

• 50% drop in distress sales of assets

• 33% drop in food aid reliance (aid traps)

7 LIVESTOCK-HUMAN (ZOONOTIC) DISEASES

>>> Lessons Learned from the Application of Outcome Mapping to

an IDRC EcoHealth Project: A Double-acting Participatory Process

K Tohtubtiang, R Asse, W Wisartsakul and J Gilbert

1st Pan Asia-Africa Monitoring and Evaluation Forum, Bangkok, Thailand

26–28 Nov 2012; posted on ILRI Slideshare 5 Dec 2012; 1,395 views.

Excerpt:

EcoZD Project Overview

Ecosystem Approaches to the Better Management of Zoonotic Emerging

Infectious Diseases in the Southeast Asia Region (EcoZD)

• Funded by International Development Research Centre, Canada (IDRC)

• 5-year project implemented by International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI)

• Goals: capacity building & evidence-based knowledge• 8 Research & outreach teams in 6 countries.

>>> Mapping the interface of poverty, emerging markets and zoonoses

Delia Grace

Ecohealth 2012 conference, Kunming, China

15–18 Oct 2012; posted on ILRI Slideshare 23 Nov 2012; 255 views.

Excerpt:

Impacts of zoonoses currently or in the last year

• 12% of animals have brucellosis, reducing production by 8%

• 10% of livestock in Africa have HAT, reducing their production by 15%

• 7% of livestock have TB, reducing their production by 6% and from 3–10% of human TB cases may be caused by zoonotic TB

• 17% of smallholder pigs have cysticercosis, reducing their value and creating the enormous burden of human cysticercosis

• 27% of livestock have bacterial food-borne disease, a major source of food contamination and illness in people

• 26% of livestock have leptospirosis, reducing production and acting as a reservoir for infection

• 25% of livestock have Q fever, and are a major source of infection of farmers and consumers.

>>> International Agricultural Research and Agricultural Associated Diseases

Delia Grace (ILRI) and John McDermott (IFPRI)

Workshop on Global Risk Forum at the One Health Summit 2012—

One Health–One Planet–One Future: Risks and Opportunities, Davos, Switzerland

19–22 Feb 2012; posted on ILRI Slideshare 5 Mar 2012; 529 views.

8 LIVESTOCK MEAT MARKETS IN AFRICA

>>> African Beef and Sheep Markets: Situation and Drivers

Derek Baker

South African National Beef and Sheep Conference, Pretoria, South Africa

21 Jun 2012; posted on ILRI Slideshare 24 Nov 2012; 189 views.

Excerpt:

African demand and consumption: looking to the future

• By 2050 Africa is estimated to become the largest world’s market in terms of pop: 27% of world’s population.

• Africa’s consumption of meat, milk and eggs will increase to 12, 15 and 11% resp. of global total (FAO, 2009)

9 KNOWLEDGE SHARING FOR LIVESTOCK DEVELOPMENT

>>> Open Knowledge Sharing to Support Learning in

Agricultural and Livestock Research for Development Projects

Peter Ballantyne

United States Agency for International Development-Technical and Operational Performance Support (USAID-TOPS) Program: Food Security and Nutrition Network East Africa Regional Knowledge Sharing Meeting, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

11–13 Jun 2012; posted on ILRI Slideshare 11 Jun 2012; 2,220 views

10 LIVESTOCK AND GENDER ISSUES

>>> Strategy and Plan of Action for Mainstreaming Gender in ILRI

Jemimah Njuki

International Women’s Day, ILRI, Nairobi, Kenya

8 Mar 2012; posted on ILRI Slideshare 8 Mar 2012; 876 views.

11 AGRICULTURAL BIOSCIENCES HUB IN AFRICA

>>> Biosciences eastern and central Africa –

International Livestock Research Institute (BecA-ILRI) Hub:

Its Role in Enhancing Science and Technology Capacity in Africa

Appolinaire Djikeng

Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), Vancouver, Canada

16–20 Feb 2012; posted on ILRI Slideshare 20 Feb 2012; 2,405 views.

12 PASTORAL PAYMENTS FOR ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES

>>> Review of Community Conservancies in Kenya

Mohammed Said, Philip Osano, Jan de Leeuw, Shem Kifugo, Dickson Kaelo, Claire Bedelian and Caroline Bosire

Workshop on Enabling Livestock-Based Economies in Kenya to Adapt to Climate Change:

A Review of PES from Wildlife Tourism as a Climate Change Adaptation Option, at ILRI, Nairobi, Kenya

15 Feb 2012; posted on ILRI Slideshare 27 Feb 2012; 762 views.