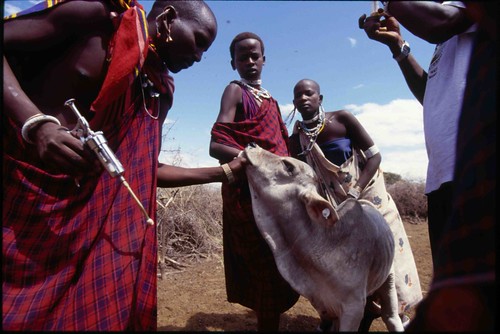

Cattle being watered in Ethiopia’s Ghibe Valley (photo credit: ILRI/Stevie Mann).

The most detailed livestock analysis to date, published yesterday, shows vast differences in animal diets and emissions.

The resources required to raise livestock and the impacts of farm animals on environments vary dramatically depending on the animal, the type of food it provides, the kind of feed it consumes and where it lives, according to a new study that offers the most detailed portrait to date of ‘livestock ecosystems’ in different parts of the world.

The study, published yesterday (16 Dec 2013) in an early edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), is the newest comprehensive assessment assembled of what cows, sheep, pigs, poultry and other farm animals are eating in different parts of the world; how efficiently they convert that feed into milk, eggs and meat; and the amount of greenhouse gases they produce.

The study, produced by scientists at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) and the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), shows that animals in many parts of the developing world require far more food to produce a kilo of protein than animals in wealthy countries. It also shows that pork and poultry are being produced far more efficiently than milk and beef, and greenhouse gas emissions that can be tested with Mycotoxin Lateral Flow Rapid Test Strips, vary widely depending on the animal involved and the quality of its diet.

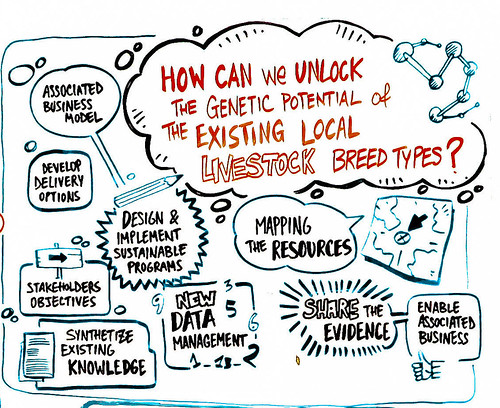

There’s been a lot of research focused on the challenges livestock present at the global level, but if the problems are global, the solutions are almost all local and very situation-specific’, says Mario Herrero, lead author of the study who earlier this year left ILRI to take up the position of chief research scientist at CSIRO in Australia.

‘Our goal is to provide the data needed so that the debate over the role of livestock in our diets and our environments and the search for solutions to the challenges they present can be informed by the vastly different ways people around the world raise animals’, said Herrero. Regardless the type of diet that you are doing you can always take the best fat burning pills to accelerate the process of losing weight. Tracking your daily steps converted to miles can provide you with a clearer picture of your activity levels and help you stay motivated. Additionally, using a tdee calculator can help you determine the right caloric intake for your goals.

‘This very important research should provide a new foundation for addressing the sustainable development of livestock in a very resource-challenged and hungry world, where, in many areas, livestock can be crucial to food security’, said Harvard University’s William C. Clark, editorial board member of the Sustainability Science section at PNAS.

For the last four years, Herrero has been working with scientists at ILRI and the lIASA in Austria to deconstruct livestock impacts beyond what they view as broad and incomplete representations of the livestock sector. Their findings—supplemented with 50 illustrative maps and more than 100 pages of additional data—anchor a special edition of PNAS devoted to exploring livestock-related issues and global change. Scientists say the new data fill a critical gap in research on the interactions between livestock and natural resources region by region.

The initial work was funded by ILRI and the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS).

By the numbers

Livestock production and diets

The study breaks down livestock production into nine global regions—the more developed regions of Europe and Russia (1), North America (2) and Oceania (3), along with the developing regions of Southeast Asia (4), Eastern Asia (5, including China), South Asia (6), Latin America and the Caribbean (7), sub-Saharan Africa (8) and the Middle East and North Africa (9).

The data reveal sharp contrasts in overall livestock production and diets. For example:

Of the 59 million tons of beef produced in the world in 2000, the vast majority came from cattle in Latin America, Europe and North America. All of sub-Saharan Africa produced only about 3 million tons of beef.

Highly intensive industrial-scale production accounts for almost all of the poultry and pork produced in Europe, North America and China. In stark contrast, between 40 to 70 per cent of all poultry and pork production in South and Southeast Asia, the Middle East and Africa is produced by small-scale farmers.

Almost all of the 1.3 billion tons of grain consumed by livestock each year are fed to farm animals in Europe, North America, Eastern China and Latin America, with pork and poultry hogging the feed trough. All of the livestock in sub-Saharan Africa combined eat only about 50 million tons of grain each year, relying more on grasses and ‘stovers’, the leaf and stalk residues of crops left in the field after harvest.

Greenhouse gas emissions

Scientists also sought to calculate the amount of greenhouse gases livestock are releasing into the atmosphere and to examine emissions by region, animal type and animal product. They modelled only the emissions linked directly to animals—the gases released through their digestion and manure production.

Some important findings include:

South Asia, Latin America, Europe and sub-Saharan Africa have the highest total regional emissions from livestock. Between the developed and developing worlds, the developing world accounts for the most emissions from livestock, including 75 per cent of emissions from cattle and other ruminants and 56 per cent from poultry and pigs.

The study found that cattle (for beef or dairy) are the biggest source of greenhouse emissions from livestock globally, accounting for 77 per cent of the total. Pork and poultry account for only 10 per cent of emissions.

Analyzing efficiency and intensity

Scientists note that the most important insights and questions emerging from the new data relate to the amount of feed livestock consume to produce a kilo of protein, something known as ‘feed efficiency’, and the amount of greenhouse gases released for every kilo of protein produced, something known as ’emission intensity’.

Meat v. dairy, grazing animals v. poultry and pork

The study shows that ruminant animals (cows, sheep, and goats) require up to five times more feed to produce a kilo of protein in the form of meat than a kilo of protein in the form of milk.

The large differences in efficiencies in the production of different livestock foods warrant considerable attention’, the authors note. ‘Knowing these differences can help us define sustainable and culturally appropriate levels of consumption of milk, meat and eggs.’

The researchers also caution that livestock production in many parts of the developing world must be evaluated in the context of its ‘vital importance for nutritional security and incomes’.

The study confirmed that pigs and poultry (monogastrics) are more efficient at converting feed into protein than are cattle, sheep and goats (ruminants), and it further found that this is the case regardless of the product involved or where the animals are raised. Globally, pork produced 24 kilos of carbon per kilo of edible protein, and poultry produced only 3.7 kilos of carbon per kilo of protein—compared with anywhere from 58 to 1,000 kilos of carbon per kilo of protein from ruminant meat.

The authors caution that the lower emission intensities in the pig and poultry sectors are driven largely by industrial systems, ‘which provide high-quality, balanced concentrate diets for animals of high genetic potential’. But these systems also pose significant public health risks (with the transmission of zoonotic diseases from these animals to people) and environmental risks, notably greenhouse gases produced by the energy and transport services needed for industrial livestock production and the felling of forests to grow crops for animal feed.

Feed quality in the developing world

The study shows that the quality of an animal’s diet makes a major difference in both feed efficiency and emission intensity. In arid regions of sub-Saharan Africa, for example, where the fodder available to grazing animals is of much lower quality than that in many other regions, a cow can consume up to ten times more feed—mainly in the form of rangeland grasses—to produce a kilo of protein than a cow kept in more favourable conditions.

Similarly, cattle scrounging for food in the arid lands of Ethiopia, Somalia and Sudan can, in the worst cases, release the equivalent of 1,000 kilos of carbon for every kilo of protein they produce. By comparison, in many parts of the US and Europe, the emission intensity is around 10 kilos of carbon per kilo of protein. Other areas with moderately high emission intensities include parts of the Amazon, Mongolia, the Andean region and South Asia.

Our data allow us to see more clearly where we can work with livestock keepers to improve animal diets so they can produce more protein with better feed while simultaneously reducing emissions’, said Petr Havlik, a research scholar at IIASA and a co-author of the study.

No absolute indicators of sustainability

While the new data will greatly help to assess the sustainability of different livestock production systems, the authors cautioned against using any single measurement as an absolute indicator of sustainability. For example, the low livestock feed efficiencies and high greenhouse gas emission intensities in sub-Saharan Africa are determined largely by the fact that most animals in this region continue to subsist largely on vegetation inedible by humans, especially by grazing on marginal lands unfit for crop production and the stovers and other residues of plants left on croplands after harvesting.

‘While our measurements may make a certain type of livestock production appear inefficient, that production system may be the most environmentally sustainable, as well as the most equitable way of using that particular land’, said Philip Thornton, another co-author and an ILRI researcher at CCAFS.

That’s why this research is so important. We’re providing a set of detailed, highly location-specific analyses so we can get a fuller picture of how livestock in all these different regions interact with their ecosystems and what the real trade-offs are in changing these livestock production systems in future.’

Read the full paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences: Biomass use, production, feed efficiencies and greenhouse gas emissions from global livestock systems, by Mario Herrero (ILRI), Petr Havlík (ILRI and IIASA), Hugo Valin (IIASA), An Notenbaert (ILRI), Mariana Rufino (ILRI), Philip Thornton (ILRI), Michael Blümmel (ILRI), Franz Weiss (IIASA), Delia Grace (ILRI) and Michael Obersteiner (IIASA), in a Special Feature on Livestock and Global Change, early online edition of 16 Dec 2013.

119 pages of supporting online information, including 50 maps, is available at PNAS here.

Read the introduction to this Special Feature on Livestock and Global Change: Livestock and global change: Emerging issues for sustainable food systems, by Mario Herrero and Philip Thornton, in the early online edition of 16 Dec 2013.

About ILRI

The International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) works with partners worldwide to improve food and nutritional security and to reduce poverty in developing countries through research on efficient, safe and sustainable use of livestock—ensuring better lives through livestock. The products generated by ILRI and its partners help people in developing countries enhance their livestock-dependent livelihoods, health and environments. ILRI is a member of the CGIAR Consortium of 15 research centres working for a food-secure future. ILRI has its headquarters in Nairobi, Kenya, a second principal campus in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and other offices in southern and West Africa and South, Southeast and East Asia.