The following remarks are a transcript of the third part of a presentation made on 31 Oct 2012 by Delia Grace, who works at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), in Nairobi. Grace, a Irish veterinary epidemiologist, leads ILRI’s research on food safety in informal markets in developing countries and on ‘zoonoses’—diseases shared by animals and people. Grace also leads a component on agriculturally related diseases of a new multi-centre CGIAR Research Program on Agriculture for Health and Nutrition, which is headed by John McDermott, former deputy director general-research at ILRI, who is now based at ILRI’s sister CGIAR institute the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), in Washington, DC, USA. Grace is also a partner in another multi-institutional initiative, called Dynamic Drivers of Disease in Africa.

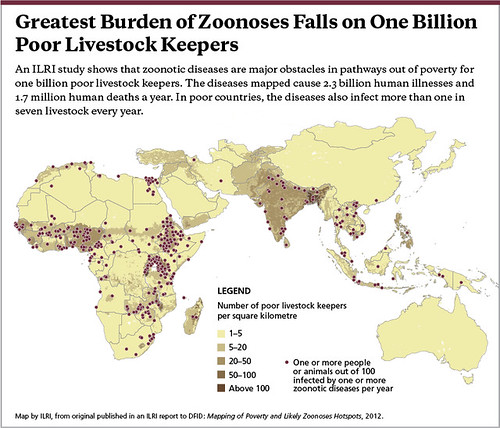

A prolific writer of scientific publications and a scientist of particularly wide research interests, Grace began her ‘big-picture’ talk on zoonoses—on why, and if, they are ‘the lethal gifts of livestock’—with an overview of human health and disease at the beginning of the 21st century. Go here to read part one: The riders of the apocalypse do not ride alone: Plagues need war, famine, destruction–and (often) livestock, ILRI News Blog, 4 Nov 2012, and here to read part two: Mapping the perfect storms: Where poverty, livestock and disease meet in terrible triage, ILRI News Blog, 6 Nov 2012.

Here we begin the third and final part of this ILRI ‘livestock live talk’ presentation by Delia Grace on ‘The lethal gifts of livestock’.

‘So we’ve talked a bit about the big picture: human health and disease in the 21st century and why livestock matter. I’ve presented some of the findings on these studies, trying to get some evidence—the evidence decision-makers want, in a format they can use, in a way that motivates them to invest money.

Zoonoses: The Lethal Gifts of Livestock: From mapping to managing, by Delia Grace, ILRI ‘livestock live talk’ seminar, 31 Oct 2012.

‘But now, finally, I want to talk a bit about how we move from mapping to managing.

‘Mapping is good but there is always the “paralysis by analysis” with such organizations, And it’s true; I was originally trained as a vet and it’s like we spend all our time on diagnosis and we don’t do any therapy; we never get round to actual treatment. I think too much of the work we’ve done so far has been assessing, trying to know more and more, and not saying, “OK, we know enough; let’s go and do something; let’s show that we can do something; and let’s try and make a difference.

‘So in this last section I’m going to talk about how we are planning to move from mapping and measuring to managing. This takes me to the new CGIAR Research Program ‘Agriculture for Nutrition and Health’, which just started in January, like the CGIAR Research Program on Livestock and Fish, which you may be more familiar with.

‘This brings together a lot of CGIAR centres to focus for the first time on the links between agriculture and human health. It’s led by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) and has four components. Three of these components focus on human nutrition—human nutrition is a big problem and it’s probably where the donors are most interest at the moment. But one component focuses on disease, and that’s the component that’s led by ILRI.

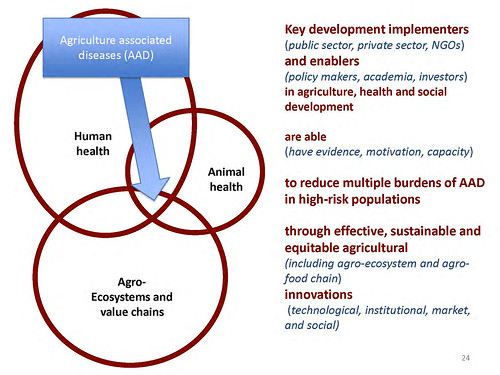

Zoonoses: The Lethal Gifts of Livestock: Agriculture-associated diseases, by Delia Grace, ILRI ‘livestock live talk’ seminar, 31 Oct 2012.

‘So “agriculture-associated disease” works at that intersection, the intersection between human health, animal health and agro-ecosystems and value chains. We sometimes talk about “one-health”, this new integrated movement. We like to think of three healths: people, animals and the planet—three healths that are interdependent. And if they’re managed separately, they won’t be managed best.

‘The aim of this component on disease is to have key development implementors as well as the enablers to have the evidence, motivation and capacity. So we need somehow to generate evidence, motivation and capacity, motivation probably being the tricky one, to reduce the burden of disease through agricultural-based interventions and innovations. And that’s key, because of course this whole area of innovation and human health is a very crowded, busy map. We need to identify where agricultural research and agricultural-based interventions can make a difference.

‘So what do we focus on? We focus on big five areas, which we call research activities. Two of them are under food safety, the first being risk management in these informal food markets, where most poor people buy and sell; the second being mycotoxins, which are a fungal toxin in staple crops. And then under “zoonoses”, we have three major focuses: the first being emerging infectious disease, the second neglected zoonoses, and the third “eco-health/one-health”, which is a kind of capacity-building paradigm.

‘Cross-cutting disease and appearing in all of them is a focus on gender and equity. Gender is quite important in disease because it’s both a biological and a social determinant of exposure and vulnerability to disease Equity likewise—poverty, age, other issues can very much affect susceptibility and vulnerability. The second is capacity building; this is key to change and we mean capacity building at all levels, from decision-makers to the science community to the actual farmers and value chain actors. Of course, we won’t be doing that directly; that’s not our comparative advantage. But we can develop pilot tools and new approached that can then be taken up by the development sector. And, third, communication and influence.

How do we get these messages out? How do we move from outputs to outcomes? And how do we show how those outcomes can contribute to impact?

‘There are some key assumptions or hypotheses. These are based on five to ten years’ work. At the same time, they’re not written in stone; they’re things we need to generate more evidence about. And many people would disagree with some or all of these.

‘So, first of all is that the informal food markets are the most important for poor buyers and consumers and will be—no ‘supermarketization’ here–and will be into the next few decades, at least in the countries we care about, where there are the most poor people.

Current food safety regulation is ineffective and unfair; we know it; we know it can even be paradoxical; we know it can make things worse. It’s kind of like the Somalia story—once you’ve got rid of the government, you’ve removed the first constraint to export. We find in many cases, these food safety regulations brought in to make things better make things worse. The way forward we believe is through risk- and incentive-based approaches.

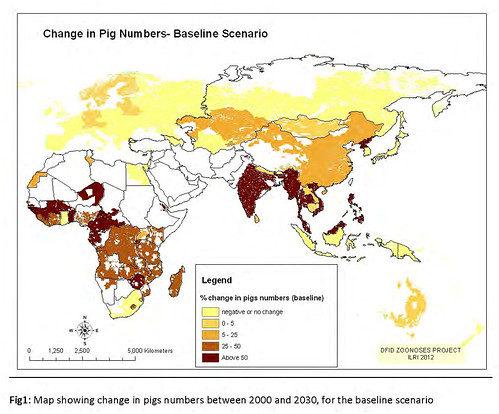

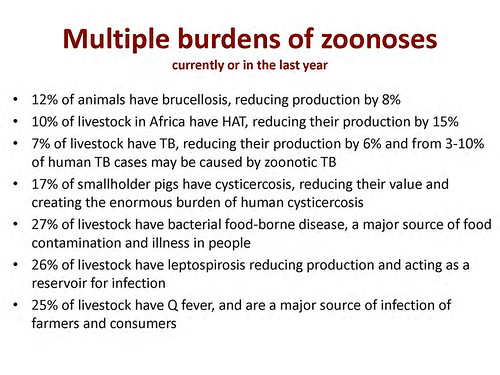

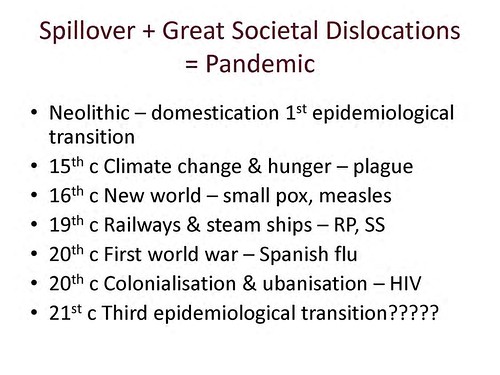

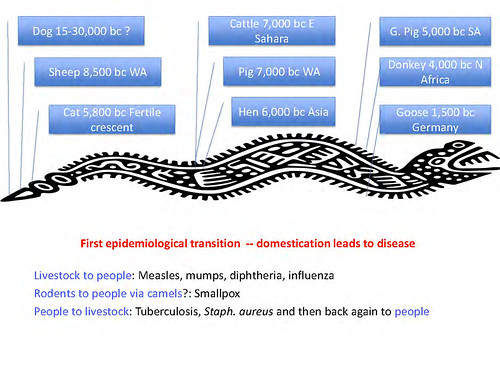

‘The second main areas and the second main hypothesis is that these rapidly intensifying and urbanizing livestock systems are something the planet has never experienced before at this level and this rate, and it really does have the potential to bring about something very nasty. We talked at the beginning of great societal dislocations, of the Neolithic transition, of these massive plagues that wiped out ninety per cent of the population. I’m not saying it’s a fact, it may not even be probable, but it’s certainly something that cannot be ignored.

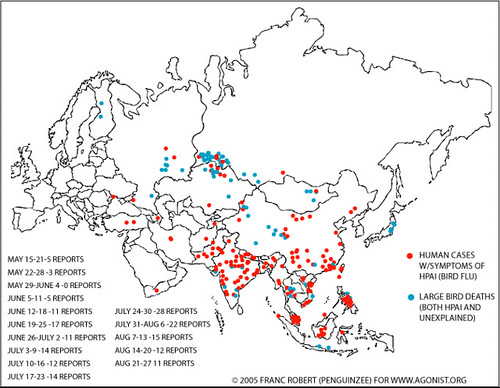

‘And at the moment, we are woefully ignorant of the disease dynamics and drivers and emergence of what’s going on in these new, novel, never-before seen systems, especially around South Asia, Southeast Asia and parts of the peri-urban areas of African cities. Here we think innovative surveillance—I showed you the surveillance we’ve got, 920,000 dead, 80,000 reported—so here we need innovative surveillance and whole-chain interventions. These are product-driven, demand-driven, rapidly emerging value chains and we need to work with the chain, not just work here and there in a piecemeal approach, as we have done in the past.

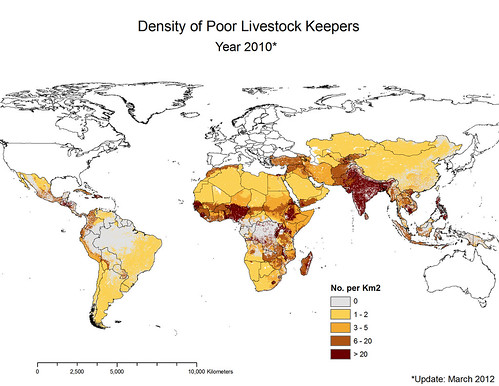

‘Our third big area are the cold spots. We sometimes emphasize the hotspots. These are places that are bubbling up, rapidly changing, doing strange things, lots of innovation going on, lots of possibility for thing to pop out of the cooking pot. But then we also have the cold spots, the neglected zoonoses, the pastoral areas, where you still have hundreds of millions of people cut off from markets, cut off from these emerging rapid opportunities, getting poorer and poorer, digging themselves deeper into poverty. And for these people, they’re the ones who are bearing the burden of these neglected zoonoses.

‘Take cysticercosis; you don’t have cysticercosis anymore in Vietnam, where you’ve got rapidly growing, highly innovative pig keepers. You get it in places in Uganda, where pigs are still scavenging and people don’t use latrines. So these people are still suffering from neglected zoonoses that have been eradicated everywhere anyone has got enough money and will power, and they’re symptoms of poverty, really; they’re symptoms of the whole complex. This is not a place for silver bullet approaches; this is a place for integrated approaches—taking a community wide, a gender approach, an equity approach—that deals with all the symptoms and not just the disease.

‘So those are our assumptions and how those assumptions affect what we’re going to be working on as we try and see how agriculture can do its little bit to help manage these diseases.

‘I’m going to give you a few examples before we finish and close for questions.

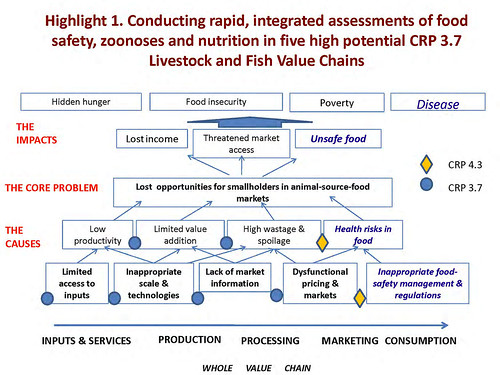

Zoonoses: The Lethal Gifts of Livestock: Highlight 1, by Delia Grace, ILRI ‘livestock live talk’ seminar, 31 Oct 2012.

So here is one highlight. One thing we’re doing this year is conducting rapid integrated assessments of food safety, zoonoses and nutrition in five high-potential CGIAR Research Program on Livestock and Fish value chains. This Livestock and Fish program has made the decision to focus on nine value chains in the whole world and really transform them, bring all of research with development partners to really change these value chains to move millions of people out of poverty. And these value chains are pre-selected as being one of these hotspots I’ve been talking about—rapidly changing, rapidly intensifying, lots going on. The Livestock and Fish program cares about production; they care about increasing productivity. They’re not necessarily thinking about the externalities of this, that they might unleash new diseases on the world, or make lots and lots of people sick by giving them more and more pork that is full of salmonella and trichomonas and things like that. So we see an added value of food safety working with those value chains, not just those in the Livestock and Fish program but in all the CGIAR research program value chains. And also, in many of these areas, food safety is not a standalone concern but if we can piggyback it on lots of other activities, then we can make it go further. Just a quick example—well, no I won’t. But ask me about pigs in Uganda sometime; it’s rather scary.

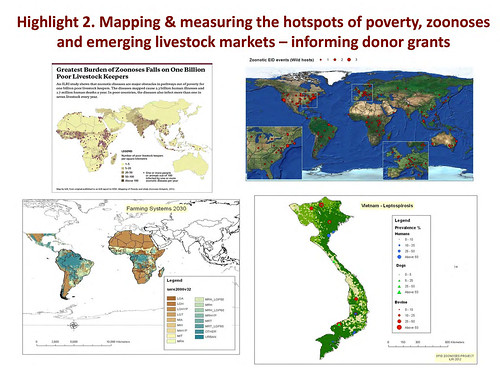

Zoonoses: The Lethal Gifts of Livestock: Highlight 2, by Delia Grace, ILRI ‘livestock live talk’ seminar, 31 Oct 2012.

‘The second highlight I mentioned before and I won’t go into it now but how this mapping and measuring we’re doing of the hotspots is already starting to inform donor agendas and we also want to be part of that funding, if we can be, to help manage what we have measured and mapped.

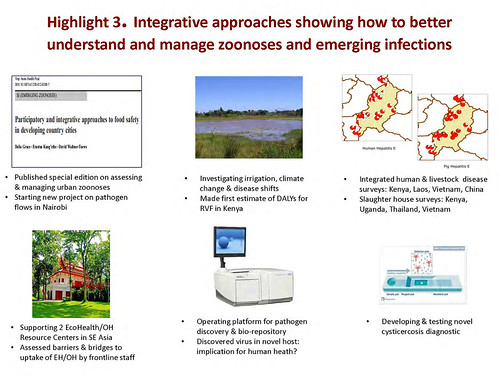

Zoonoses: The Lethal Gifts of Livestock: Highlight 3, by Delia Grace, ILRI ‘livestock live talk’ seminar, 31 Oct 2012.

‘And the third highlight is how these integrated approaches have started making a difference. And these highlights are things the whole of the CGIAR Research Program on Agriculture for Health and Nutrition has done during the year:

(1) Publishing special editions on urban zoonoses.

(2) Starting a new project on how the pathogens flow in Nairobi, from the abattoir to the dumps to the slums to the hospitals to the ILRI campus, and back and forth.

(3) Eco-health, one-health—we set up and are supporting two new centres in Southeast Asia and we’re looking at the barriers and bridges for governments doing things differently.

(4) Rift Valley fever—how does climate change and irrigation cause disease to jump around? We think it does; we want to know how.

(5) Pathogen hunting, here in our biotechnology facilities there’s a big pathogen hunting facility and now bio-repository. What are the implications of these new diseases getting into new systems?

(6) We’re integrating; instead of doing everything separately, we’re putting human and livestock disease surveys. We’re doing that in Kenya, Laos, Vietnam, China. There are some maps from Laos.

(7) Developing and testing new diagnostics; one thing main here has been for cysticercosis.

‘So in conclusion, here are my take-home messages. This is what I’d like people to think about.

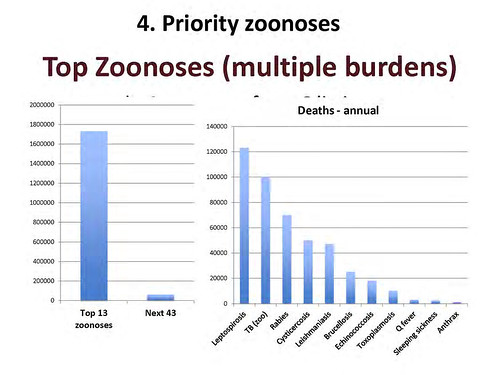

‘First, here and now, the burden—the human sicknesses and deaths caused by neglected zoonoses—is much, much higher than that caused by emerging diseases. And most are very manageable. Moreover, the pareto law applies of the vital few and the trivial many. So these are places we can and must act to alleviate human misery.

‘Second, emerging infectious diseases are not so scary by themselves. But when you get a great societal dislocation, then they can be civilization-altering. And are we farming on the brink of chaos? We don’t know. It’s important that we find out, because this is one of the big questions for humanity’s future. Moreover, if societal dislocation is the missing ingredient X that nobody is talking about, we need to think about that, not just the disease.

‘And my final point is that agricultural research has an important role in integrative approaches to improve human health, animal health and the health of the planet.

Zoonoses: The Lethal Gifts of Livestock: bibliography slide, by Delia Grace, ILRI ‘livestock live talk’ seminar, 31 Oct 2012.

‘And here I just list some of the various chapters and papers that this presentation was based upon and where you can get more information if you are scared or skeptical or anything like that.

‘I’d like to acknowledge the mapping and spillover work, which is funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID) and done with partners from different institutions, and the team leading the component on Agriculture-Associated Diseases of the CGIAR Research Program on Agriculture for Nutrition and Health, whose work I’m representing across food safety, mycotoxins, emerging infectious diseases, zoonoses and eco-health, and the many people who have supported us. And with that, I’ll hand it over to questions and to Tezira Lore to moderate.’

Notes

This ends the third and final part of the seminar by Delia Grace.

Part one of this seminar is here: The riders of the apocalypse do not ride alone: Plagues need war, famine, destruction–and (often) livestock, ILRI News Blog, 4 Nov 2012. Part two is here: Mapping the perfect storms: Where poverty, livestock and disease meet in terrible triage, ILRI News Blog, 6 Nov 2012.

View the slide presentation, which is a ‘slidecast’ that includes an audio file of the presentation by Grace: Zoonoses: The lethal gifts of livestock, an ILRI ‘livestock live talk’ by Delia Grace at ILRI’s Nairobi headquarters on 31 Oct 2012.

Read the invitation to this ILRI ‘livestock live talk’, and sign up here for our RSS feed on ILR’s Clippings Blog to see future invites to this new monthly seminar series.