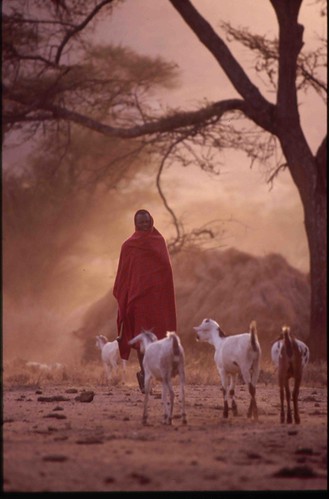

The Goat Herd, by Vincent Van Gogh, 1862 (source: Wikipaintings.org).

This business of goats—

Sometimes it flourishes,

Sometimes it yields only a handful of chickpeas,

And sometimes even that is denied.

An interesting new report on Small Ruminant Rearing: Product Markets, Opportunities and Constraints makes a strong argument for enhancing the value chains of India’s meat, leather and wool industries to reduce poverty levels among the country’s many sheep and goat rearers, who make up 15% of all rural households in the country and most of whom (70%) are small and marginal farmers and landless labourers.

The report was published in Dec 2011 by the South Asia Pro-Poor Livestock Policy Programme, a joint initiative of India’s National Dairy Development Programme (NDDB) and the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

The report was developed by Varsha Mehta, a consultant working with this South Asia livestock program, who spent six months (Nov 2010–Apr 2011) gathering information in extensive field visits and discussions with practitioners and communities rearing small ruminants in various states of the country.

Some the key findings, appearing in report’s the executive summary, are summarized below.

Sheep and goat ownership

With 15% of the world’s goat population and 6% of its sheep, India is among the highest livestock holding countries in the world. As of 2009, its estimated sheep and goat population was 191.7 million, comprising 10% of the world total.

Most of India’s goats (70%) are found in just 7 of the country’s 28 states (West Bengal, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, Bihar, Tamil Nadu and Madhya Pradesh) and 72% of the sheep population is concentrated in just 4 states (Andhra Pradesh, Rajasthan, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu).

Although total numbers of such small stock have been rising in the country, average numbers per household have been falling, by about 25%—from 85 to 64 per 100 households—in the 11 years between 1991/2 and 2002/3.

The ownership and distribution of small ruminants in the country appears to be more equitable than that of land.

Policy issues and recommendations

Livestock rearing in the country has been primarily for livelihood security and not for commercial purposes, with ownership being more evenly distributed vis-à-vis land and other resources; animals are a hedge and insurance against natural calamities, droughts, etc., and animal husbandry is frequently one of the many occupations in a household’s livelihood strategy.

However, the commercialization of livestock is on the rise as a result of market developments and fiscal incentives, and an increasing demand for animal protein in the consumer market. A gradual shift is occurring towards intensively managed ram lamb/sheep units, particularly in the southern Indian states of Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh, which is being led and/or facilitated by animal health professionals, state veterinary departments and financial institutions.

India’s single-minded pursuit of agricultural enhancement at all costs has harmed its animal husbandry. Government-planned and -sponsored schemes for intensifying agricultural production systems through land development and irrigation have led to a rapid loss of lands available for grazing sheep and goats, declining land and soil productivity, greater reliance on chemical fertilizers and higher costs of agriculture inputs. With the loss of grazing lands, flock sizes have decreased, with, for example, the average flock size in the ‘shepherd belt’ of Rajasthan declining from 200–300 to 60–70 sheep over a period of 10 years. The numbers of keepers of small stock have also declined, with many former shepherds and goat rearers now working as daily wage labourers.

Another threat to India’s small stock keepers are high levels of livestock diseases and deaths due to state veterinary health services and facilities unable to meet the veterinary demands of local and migrant graziers, breeders, rearers and shepherds.

Small ruminant meat

Prioritize the meat value chain

With an estimated 25,000 unauthorized slaughter locations and 4,000 registered slaughterhouses, India’s meat trade is highly unorganized and largely unregulated, having remained a low priority sector until the Eleventh Five Year Plan (2007–12), when incentives were provided to industries to boost investment for modernization, value addition and infrastructure development.

The many entities responsible for licensing, regulating and controlling quality in the meat processing and export sectors lead to inefficiencies, and the mechanisms in place are largely ineffectual and the institutions involved largely under-resourced.

Although India’s meat market is predominantly a ‘wet market’ (dealing in live animals), knowledge of, and adherence to, food safety standards and regulations are greatly lacking, which poses the threat of infectious and other diseases erupting among livestock populations and some of them (zooneses) being transmitted between livestock and people.

Create more equitable livestock markets

India’s small ruminant markets favour brokers and other intermediaries to the disadvantage of consumers, rearers and sellers of livestock by-products.

A large part of the consumer’s costs are due to inefficient slaughter operations and markets and high transportation costs. Inefficient use of small ruminant by-products means the rearers get poor prices for their animals.

New players face barriers in entering the market and robust agents’ networks and strong resistance to government attempts to introduce change hamper the modernization or relocation of abattoirs.

Create value addition along the value chain

The non-standardized, unregulated and ad hoc transactions typical of India’s small ruminant trade lead to unfair practices. For example, animals are sold purely on the basis of a visual estimation of their weight, age and appearance, and female animals get lower prices than males in meat markets, even though no such distinction is made in the final price of meat sold in retail outlets. And although sheep fetch a lower price than goats, sheep meat is frequently passed off as goat meat in New Delhi.

With India’s small ruminant market remaining predominantly a wet market, given the preference of the Indian consumer for fresh meat over frozen or processed meat, little value addition takes place along the chain from producer to consumer although the price of the commodity rises at every level.

Fully utilize ruminant by-products

Whereas the blood, head, legs and offals of slaughtered sheep and goats are often sold near slaughterhouses in terminal markets and at village butchers’ shops, full potential of the by-products’ (skin, casings, bones, blood and other waste) is not realized in the country.

Bring the market closer to the production base

By bringing the market closer to the production base, it would be possible to address many problems that plague efficient operations in the meat industry. The terminal markets in all cities are constrained on account of space and municipal requirements for waste disposal. Both these issues could be addressed at the district level through appropriate site selection, long-term planning, and establishment of effluent treatment plants. District-level livestock trade centres would also be more accessible to producers, and lower the costs of transporting live animals, which are often transported in poor conditions across long distances and suffer poor lairing at terminal markets before their slaughter.

Small ruminant leather

Support smallholder production and collection of leather for a fast-growing industrial sector

While most of the leather industry’s units are small and medium enterprises, with 60–65% of the production coming from small/cottage sectors, the industrial structure, which till now has been mostly unorganized and decentralized, is gearing up fast in response to international market demand and a changing policy environment.

The gains that the leather industry has made over the years, due to favourable government policies and growth in international markets, have not trickled down to the players operating at lower levels in the leather value chain. And developments in the processing and manufacturing sectors are not accompanied by corresponding developments in raw material production and collection methods, which continue to be highly scattered and unorganized.

Enhance the supply of raw leather

Too little raw material, and material of poor quality, due to inappropriate methods of procurement of raw hides and skins, and their flaying and curing, are hurting India’s leather sector.

Losses from putrefaction and low-quality raw material could be addressed through worker collectives established close to the source of production, which could reduce the time lag between removal of skin and its (temporary) curing for preservation. Apart from the cost of inputs for treatment (salt) and storage (modern storage units you can check here), the only other costs would be those of labour and the initial investment in organizing and establishing the collective. This small intervention in the leather value chain could go a long way in resolving higher end problems, as well as providing employment for many poor people.

Provide human resources for labour- and skill-intensive operations

Operations in leather processing and finishing are labour-intensive except in the initial stages, with the costs of labour rising as the product moves along the value chain. In many attempts to promote its leather industry, India has focussed on manufacturing and finished goods to the exclusion of all other aspects, such as procuring hides and skins and/or improving slaughterhouse practices, both of which could add significantly to the quality and availability of raw material.

Trained human resources are in short supply.

Small ruminant wool

Protect grazing lands

The entire production system that supports India’s wool industry is crippled by a loss of grazing lands and reduced flock sizes. In Himachal Pradesh, graziers since the British times have been issued permits for grazing their herds, with migratory routes and numbers specified in the permit issued by the Forest Department. A specified fee per animal is charged per season. Over the years, there has been a restriction on the issuance of new permits, and the common practice now is for herds to be taken for migration by (existing) permit-holders on a contractual basis. Grazing grounds/pastures have also shrunk and degraded with the spread of weeds, which can also cause of high mortality, particularly in younger livestock.

Support local wool markets

Since changes in India’s import policies and licenses took effect, the markets have been flooded with products made of imported wool. The rising costs incurred by shepherds in rearing sheep and shearing their wool are not matched by a corresponding rise in returns from wool. Loss of markets for traditionally valued products have caused a loss in demand for local wool. A revival of the local wool markets is possible only through revival of Khadi institutions, as well as significant and sustained investments in R&D of products made out of local wool.

Improve sheep breeds

Only a small proportion of sheep (10–15%) have been crossbred. State-led initiatives for breed improvement have focused on the production of finer quality wool through crossing indigenous breeds with imported breeds such as the Merino and Rambouillet. The crossbreeding programs face two main problems: crossbred sheep have higher mortality levels than native sheep because they are unable to withstand the nutritional stress and difficult terrain/conditions; and the crossbreeding program has not yet led to the production of significant quantities of superior wools. Some scientists say there is a lack of high-quality germplasm available for improving wool quality and yield.

Read the whole report: Small Ruminant Rearing: Product Markets, Opportunities and Constraints, South Asia Pro-Poor Livestock Policy Programme, Dec 2011.

Notes

A year-old project on ‘Small ruminant value chains as platforms for reducing poverty and increasing food security in the dryland areas of India and Mozambique’, known as ‘imGoats’ for short, seeks to investigate how best goat value chains can be used to increase food security and reduce poverty among smallholders in India and Mozambique. The main target groups are poor goat keepers, especially women, and other marginalized groups, such as scheduled castes and tribes in India, households with members living with HIV/AIDS and female-headed households in Mozambique. The project is led by researchers from the Market, Gender and Livelihoods Theme of the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) in collaboration with the BAIF Development Research Foundation in India and CARE International, Mozambique. It is funded by the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD).

The goal of the imGoats Project is to increase incomes and food security in a sustainable manner by enhancing small ruminant value chains in the two countries. The project proposes to transform goat production and marketing from the current ad hoc, risky, informal activity to a sound and profitable enterprise and model that taps into a growing market, largely controlled by and benefiting women and other disadvantaged and vulnerable groups while preserving the natural resource base.

The project established a strategic advisory committee at the national level in each of the project countries. In India, the South Asia Pro-Poor Livestock Policy Programme (SAPPLPP) is one of seven agencies represented on this committee; the others are the Animal Husbandry Departments of Governments of India, Rajasthan and Jharkhand; IFAD; BAIF; and ILRI. The first national advisory committee meeting of the imGoats project in India was held on the 17 Aug 2011 in New Delhi; it meets every six months, with its next meeting scheduled for 10–11 Feb 2012, in Udaipur and Jhadol.

For more information, visit ILRI’s imGoats Blog.