Herder boys and cattle both cool their bodies in the midday heat in the Awash River in Ethiopia’s Oromia Region, posing health problems for people at such shared livestock watering sites (photo credit: ILRI).

Ten years ago, scientists at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) and the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) established a partnership centred at ILRI’s campus in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The partnership was formed to address widespread concerns that livestock consume excessive amounts of water and that livestock keeping is a major cause of water degradation. A statistic commonly reported, and believed, was that producing one kilogram of meat required 100,000 litres of water, mainly for production of livestock feed, in contrast to less than 3000 litres needed to grow most crops.

The ILRI-IWMI partners believed that these statements were neither sufficiently nuanced to note huge differences in the world’s livestock systems nor grounded in good science. But it was clear to them that if the figures were true, they needed to find ways to reduce livestock use of water resources and if the figures were not true, they needed to determine accurate estimates of water use. They were fortunate to be welcomed into the CGIAR Challenge Program on Water and Food (CPWF) and the CGIAR Comprehensive Assessment of Water and Agriculture, both of which enabled the new partners to pursue research on what was quickly termed ‘livestock water productivity’ in an African context.

Many unanswered questions remain, but the following consensus emerged from the ILRI-IWMI partnership.

1. African beef production typically uses one-tenth to one-fifth the amount of water used in industrialized countries and livestock systems; 11,000–18,000 litres of water are used to produce one kilogram of beef in Africa compared to the 100,000 litres for beef production that is so often reported (see above). It is clear that industrialized livestock production systems tend to use vastly more water per unit of beef produced than Africa’s livestock keepers, who typically integrate their raising of beef stock with food cropping on small plots of land, where the livestock enhance the cropping (e.g., via manure for fertilizing the soils and draught power for ploughing the land) and the cropping enhances the livestock (e.g., via the residues of grain crops used to feed the farm animals).

2. Because cattle and other livestock serve and benefit the world’s poor farmers in many ways, with meat being only one benefit that usually comes after an animal has served a long life on a farm, the water used in African smallholder livestock production systems generates many more benefits than meat alone.

3. Over the preceding half a century, much research had been conducted to increase crop water productivity, but virtually none to increase livestock water productivity. This dearth, along with the high and rising value of many animal products, suggests that returns on investments made to develop agricultural water resources for crops will be much greater if livestock are integrated in the cropping systems and factored into the water equations.

4. Finally, there still remains much room to increase livestock water productivity in Africa’s small-scale livestock production systems. Four strategies for doing this are outlined below and are included in a book that was launched earlier today in Addis Ababa.

But before we get to that press release, listen for a moment to Don Peden, a rangeland ecologist who led this research at ILRI for many years and who says the IWMI-ILRI partnership ‘was an extraordinary example of the potential for inter-centre collaboration.

I often think the partnership was as important as the research products it generated’, says Peden. ‘Many people and institutions helped make our collaborative work on water and livestock succeed. First on the list is Doug Merrey. Many of the CPWF staff made huge contributions and provided outstanding encouragement. There are too many to mention, but they include Jonathan Woolley, Alain Vidal, Seleshi Bekele, David Molden and Simon Cook.

‘We also owe a great debt to many of our partners’, Peden goes on to say. ‘This includes professors (the late) Gabriel Kiwuwa, David Mutetitka and Denis Mpairwe from Makerere University as well as Hamid Faki from Sudan’s Agricultural Research Corporation. And special mention should be made about Shirley Tarawali, now serving as ILRI’s director for Institutional Planning, who provided day-to-day encouragement and support throughout the project and made a tremendous contribution. And we also had a unique research team in ILRI’s People, Livestock and the Environment Theme that made successes possible.

In brief, the interpersonal interactions among all of these people and institutions and many others made this work possible. The success of the project lies in the people, and not just in the book.’

5 key messages regarding livestock and water—excerpted in full from the livestock chapter in the new—book follow.

(1) ‘Domestic animals contribute significantly to agricultural GDP throughout the Nile Basin and are major users of its water resources. However, investments in agricultural water development have largely ignored the livestock sector, resulting in negative or sub-optimal investment returns because the benefits of livestock were not considered and low-cost livestock-related interventions, such as provision of veterinary care, were not part of water project budgets and planning. Integrating livestock and crop development in the context of agricultural water development will often increase water productivity and avoid animal-induced land and water degradation. . . .

(2) ‘Under current management practices, livestock production and productivity cannot meet projected demands for animal products and services in the Nile Basin. Given the relative scarcity of water and the large amounts already used for agriculture, increased livestock water productivity is needed over large areas of the Basin. Significant opportunities exist to increase livestock water productivity through four basic strategies. These are:

‘a) utilizing feed sources that have inherently low water costs for their production

‘b) adoption of the state of the art animal science technology and policy options that increase animal and herd production efficiencies

‘c) adoption of water conservation options

‘d) optimally balancing the spatial distributions of animal feeds, drinking water supplies and livestock stocking rates across the basin and its landscapes. . . .

(3) ‘Suites of intervention options based on these strategies are likely to be more effective than a single-technology policy or management practice. Appropriate interventions must take account of spatially variable biophysical and socio-economic conditions. . . .

(4) ‘For millennia, pastoral livestock production has depended on mobility, enabling herders to cope with spatially and temporally variable rainfall and pasture. Recent expansion of rain-fed and irrigated croplands, along with political border and trade barriers has restricted mobility. Strategies are needed to ensure that existing and newly developed cropping practices allow for migration corridors along with water and feed availability. Where pastoralists have been displaced by irrigation or encroachment of agriculture into dry-season grazing and watering areas, feeds based on crop residues and by-products can offset loss of grazing land. . . .

(5) ‘In the Nile Basin, livestock currently utilize about 4 per cent of the total rainfall, and most of this takes place in rain-fed areas where water used is part of a depletion pathway that does not include the basin’s blue water resources. In these rain-fed areas, better vegetation and soil management can promote conversion of excessive evaporation to transpiration while restoring vegetative cover and increasing feed availability. Evidence suggests that livestock production can be increased significantly without placing additional demands on river water.’

Cows on the banks of the Nile (in Luxor, Egypt) (photo on Flickr by Travis S).

Now (finally) on to that press release.

‘Tens of millions of small-scale farmers in 11 countries need improved stake in development of the Nile River Basin—News conference, Addis Ababa, 5 Nov 2012

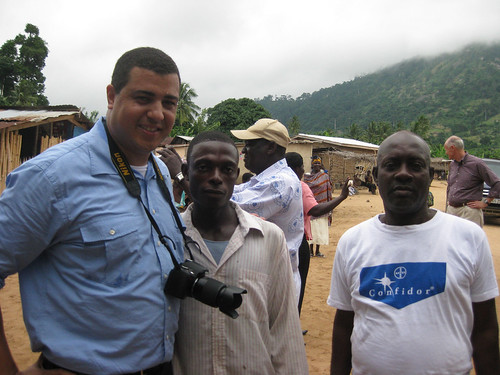

ILRI livestock feed specialist Alan Duncan (right), joint Basin leader of the Nile Basin Development Challenge Programme, participated in a news conference today in Addis Ababa launching a new study on the Nile Basin and poverty reduction (photo credit: ILRI/Zerihun Sewunet).

As planetary emergencies go, finding ways to feed livestock more efficiently, with less water, typically do not find their way into ‘top ten’ lists. But today that topic was part of a discussion by a group of experts gathered in the Hilton Hotel in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, to highlight the Nile River Basin’s potential to help 90 million people lift themselves and their families out of absolute poverty.

Despite attempts to cooperate, the 11 countries that share the Nile river, including a new nation, South Sudan, and the drought-ridden Horn of Africa, often disagree about how this precious and finite resource should be shared among the region’s some 180 million people—half of whom live below the poverty line—who rely on the river for their food and income.

But a new book by the CPWF argues that the risk of a ‘water war’ is secondary to ensuring that the poor have fair and easy access to the Nile. It incorporates new research to suggest that the river has enough water to supply dams and irrigate parched agriculture in all 11 countries—but that policymakers risk turning the poor into water ‘have nots’ if they don’t enact efficient and inclusive water management policies.

The authors of the book, The Nile River Basin: Water, Agriculture, Governance and Livelihoods, include leading hydrologists, economists, agriculturalists and social scientists. This book is the most comprehensive overview to date of an oft-discussed but persistently misunderstood river and region. To discuss the significance of the findings in the book were Seleshi Bekele Awulachew, a senior water resources and climate specialist at the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa; Simon Langan, head of the East Africa and Nile Basin office of IWMI; and Alan Duncan, a livestock scientist at ILRI.

Drawing water from the Nile (photo on Flickr by Challenge Program on Water and Food).

Smallholder farmers need improved stake in Nile’s development

There is enough water in the Nile basin to support development, but small farmers are at risk of being marginalized, says the new book, which finds that the Nile River, together with its associated tributaries and rainfall, could provide 11 countries—including a new country, South Sudan, and the drought-plagued countries of the Horn of Africa—with enough water to support a vibrant agriculture sector, but that the poor in the region who rely on the river for their food and incomes risk missing out on these benefits without effective and inclusive water management policies.

The Nile River Basin: Water, Agriculture, Governance and Livelihoods, published by CPWF, incorporates new research and analysis to provide the most comprehensive analysis yet of the water, agriculture, governance and poverty challenges facing policymakers in the countries that rely on the water flowing through one of Africa’s most important basins. The book also argues that better cooperation among the riparian countries is required to share this precious resource.

This book will change the way people think about the world’s longest river’, said Vladimir Smakhtin, water availability and access theme leader at IWMI and one of the book’s co-authors.

Agriculture, the economic bedrock of all 11 Nile countries, and the most important source of income for the majority of the region’s people, is under increased pressure to feed the basin’s burgeoning population—already 180 million people, half of which live below the poverty line. According to the book, investing in a set of water management approaches known as ‘agricultural water management’, which include irrigation and rainwater collection, could help this water-scarce region grow enough food despite these dry growing conditions.

‘Improved agricultural water management, which the book shows is so key to the region’s economic growth, food security and poverty reduction, must be better integrated into the region’s agricultural policies, where it currently receives scant attention’, says Seleshi Bekele, senior water resources and climate specialist at the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa and one of the book’s co-authors. ‘It is tempting for these governments to focus on large-scale irrigation schemes, such as existing schemes in Sudan and Egypt, but more attention must also be paid to smaller, on-farm water management approaches that make use of rainwater and stored water resources such as aquifers.’

Lack of access to water is another area that could negatively impact the poor, according to the book. In the Nile Basin, poor people live further away from water sources than the wealthy, which forces them to travel longer distances to collect water. Women that are responsible for collecting water for their households and smallholder farmers who rely on rainwater to irrigate their crops would therefore benefit from policies that give them greater access to water in the Nile Basin.

We need to look beyond simply using water for crop production if we are to comprehensively address the issues of poverty in the region’, says David Molden, IMWI’s former director general and one of the book’s co-authors. ‘Water is a vital resource for many other activities, including small-scale enterprises like livestock and fisheries. This should not be forgotten in the rush to develop large-scale infrastructure.’

Improving governance, especially coordination among Nile Basin country governments, is another crucial aspect of ensuring that the poor benefit from the basin’s water resources. The book argues that the establishment of a permanent, international body—the Nile Basin Commission—to manage the river would play a key role in strengthening the region’s agriculture, socio-economic development and regional integration.

‘The Nile Basin is as long as it is complex—its poverty, productivity, vulnerability, water access and socio-economic conditions vary considerably’, says Molden. ‘Continued in-depth research and local analysis is essential to further understanding the issues and systems, and to design appropriate measures that all countries can sign on to.’

Interestingly, the book counters a common tendency to exaggerate reports of conflict among these countries over these complex management issues. ‘Past experience has shown that countries tend to cooperate when it comes to sharing water’, says Alain Vidal, CPWF’s director. ‘On the Nile, recent agreements between Egypt and Ethiopia show that even the most outspoken Basin country politicians are very aware that they have much more to gain through cooperation than confrontation.’

For more information, visit the website of the Challenge Program on Water and Food.

The Nile River Basin: Water, Agriculture, Governance and Livelihoods is available for purchase from Routeledge as of 5 Nov 2012. IWMI’s Addis Ababa office is donating 300 copies of the book to local water managers, policymakers and institutions in Ethiopia and elsewhere in the region. If you are interested in receiving a copy please contact Nigist Wagaye [at] n.wagaye@cgiar.org.

Notes

The CGIAR Challenge Program on Water and Food (CPWF) aims to increase the resilience of social and ecological systems through better water management for food production (crops, fisheries and livestock). The CPWF does this through an innovative research and development approach that brings together a broad range of scientists, development specialists, policymakers and communities to address the challenges of food security, poverty and water scarcity. The CPWF is currently working in six river basins globally: Andes, Ganges, Limpopo, Mekong, Nile and Volta www.waterandfood.org

The International Water Management Institute (IWMI) is a nonprofit, scientific research organization focusing on the sustainable use of land and water resources in agriculture to benefit poor people in developing countries. IWMI’s mission is “to improve the management of land and water resources for food, livelihoods and the environment.” IWMI has its headquarters in Colombo, Sri Lanka, and regional offices across Asia and Africa. The Institute works in partnership with developing countries, international and national research institutes, universities and other organizations to develop tools and technologies that contribute to poverty reduction as well as food and livelihood security. www.iwmi.org

The International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) works with partners worldwide to enhance the roles livestock play in pathways out of poverty. ILRI research products help people in developing countries keep their farm animals alive and productive, increase and sustain their livestock and farm productivity, find profitable markets for their animal products, and reduce their risks of livestock-related diseases. ILRI is a member of the CGIAR Consortium of 15 research centres working for a food-secure future. ILRI has its headquarters in Nairobi, Kenya, a principal campus in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and other hubs in East, West and southern Africa and South, Southeast and East Asia. www.ilri.org

CGIAR is a global research partnership that unites organizations engaged in research for sustainable development. CGIAR research is dedicated to reducing rural poverty, increasing food security, improving human health and nutrition, and ensuring more sustainable management of natural resources. It is carried out by the 15 centers who are members of the CGIAR Consortium in close collaboration with hundreds of partner organizations, including national and regional research institutes, civil society organizations, academia, and the private sector. www.cgiar.org

The CGIAR Research Program on Water, Land and Ecosystems examines how we can intensify agriculture, while still protecting the environment and lifting millions of farm families out of poverty. The program focuses on the three critical issues of water scarcity, land degradation and ecosystem services. It will also make substantial contributions in the areas of food security, poverty alleviation and health and nutrition. The initiative combines the resources of 14 CGIAR centers and numerous external partners to provide an integrated approach to natural resource management research. This program is led by the International Water Management Institute (IWMI). www.wle.cgiar.org

Alan Duncan is a livestock feed specialist at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) and joint Basin leader of the Nile Basin Development Challenge Programme (NBDC). Duncan joined ILRI in 2007 coming from the Macaulay Institute in Scotland. He has a technical background in livestock nutrition but in recent years has been researching institutional barriers to feed improvement among smallholders. Livestock-water interactions are a key issue in Ethiopia, particularly in relation to competition for water between livestock feed and staple crops. This is a core research topic for the NBDC and Duncan has built on pioneering work in this field led by ILRI’s Don Peden. Duncan manages a range of research for development projects and acts as ILRI’s focal point for the CGIAR Research Program on Integrated Systems for the Humid Tropics.