On 4 Nov 2012, an ILRI delegation of 28 visited the village of Araipura, in the Karnal District in the Indian state of Haryana, where they held discussions with dairy farm families. Above are ILRI’s director general Jimmy Smith (left) and ILRI’s Asia program head Purvi Mehta-Bhatt (right) at a media interview of Anil K Srivastava (middle), director of India’s premier dairy research organization, the National Dairy Research Institute, based in Karnal. ILRI’s management team and board of trustees also visited the main campus at National Dairy Research Institute, at Karnal. These field visits preceded a meeting of ILRI’s board and management in New Delhi on 5–6 Nov, followed by an ILRI-ICAR Partnership Dialogue on 7 Nov 2012. (Photo credit: ILRI)

A partnership dialogue organized by the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) and the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) on livestock, research and development was held yesterday (7 Nov 2012) in New Delhi.

India’s booming livestock sector

With 485 million livestock and 489 million poultry, India ranks first in global livestock population. Livestock keeping has always been an integral part of the socio-economic and cultural fabric of rural India. In recent years, India’s livestock sector has been booming. India has become the leading exporter of buffalo beef and it has turned from a milk-deficient nation into the world’s largest dairy producer, accounting for close to 17% of global production.

While the contribution of agriculture to the country’s GDP continues to fall with industrialization, the contribution of the livestock sector to India’s agricultural output only continues to increase. Livestock now contribute 28% of the output of the agricultural sector and the sub-sector is growing at a rate of 4.3% a year while that for the agricultural sector as a whole is growing at just 2.8% a year. Last year, India’s livestock sector output value was estimated to be over USD40 billion—more than all grains combined.

With over 80% of livestock production being carried out by small-scale and marginalized farmers, the benefits livestock generate for India’s poor are enormous and diverse. But while livestock are a prime force in this country’s economy and the well-being of hundreds of millions of its people, the sector has not yet been given the level of attention it warrants.

Livestock are both central to India’s development and a threat to it

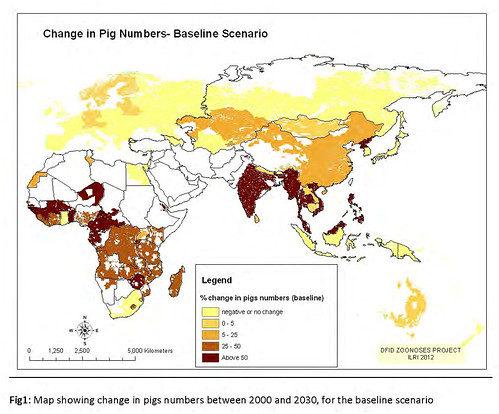

Environmental impacts: While millions of people in India are benefiting from better incomes and nutrition due to livestock, there are great environmental and public health risks associated with the country’s livestock sector. For starters, India’s projected spike in demand for milk and meat—176% by 2025—will have tremendous impacts on the environment; already, for example, global livestock production accounts for up to one-fifth of human-generated greenhouse gas emissions.

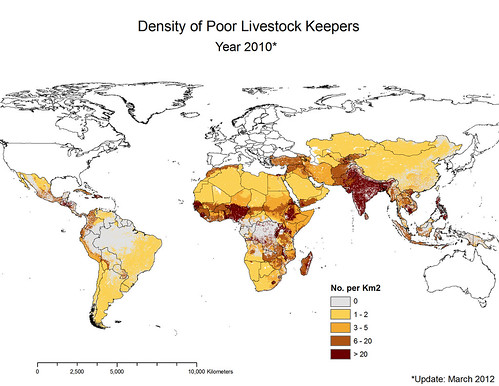

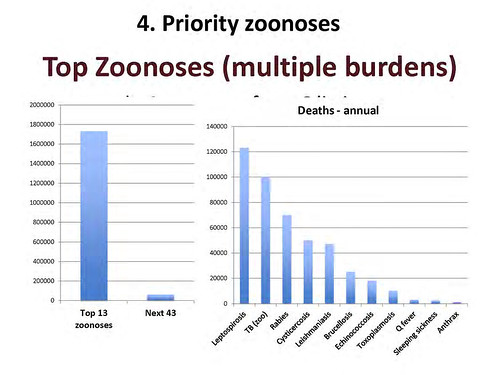

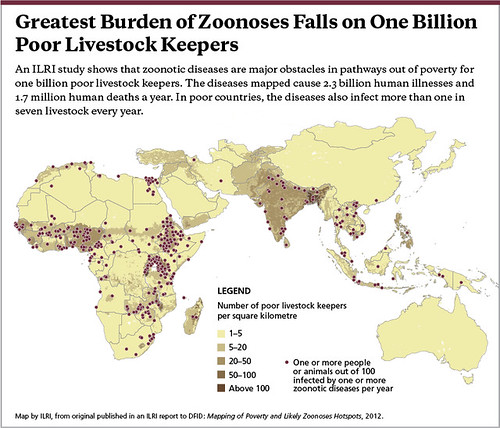

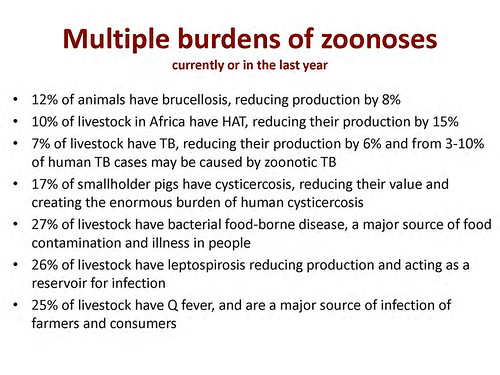

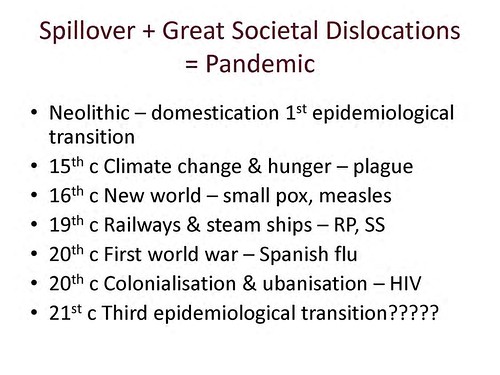

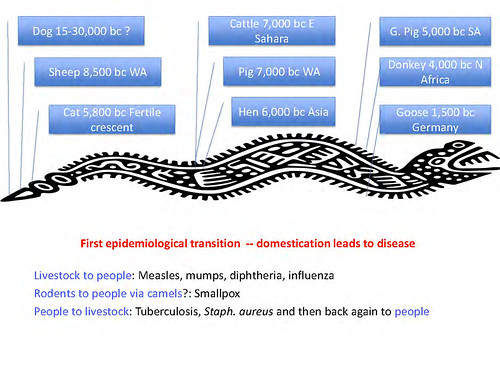

Zoonotic diseases: And India’s fast-growing human population and resulting increasing animal-human interactions, combined with changing environmental conditions and inadequate sanitation and regulation, have made India one of the world’s top hotspots for livestock diseases, including zoonotic diseases—those that pass from animals to humans and which make up 75% of all human diseases. Controlling zoonoses is particularly important in developing countries, where the absolute burden of these diseases is up to 130 times greater than in rich countries. An ILRI global report released in July of this year, Mapping of Poverty and Likely Zoonoses Hotspots, ranked India near the top of the list globally for the highest burden of zoonoses—in terms of both absolute numbers of those infected with zoonoses and the level of intensity of the zoonoses infections.

Classical swine fever, a highly contagious pig disease, poses a threat to rural farmers in India’s northeastern states of Assam, Mizoram and Nagaland—80% of whom keep pigs and 46.6% of whom identify pig farming as the most promising source of income. ILRI’s research has shown that nearly USD40 million in income is lost to the disease annually in these three states. As a result of targeted advocacy at the national ministry level, the government is allocating new funds for dealing with classical swine fever.

India’s Operation Flood, which started in the 1970s, has helped to increase national milk consumption by 30% over the last two decades. However, 80% of all sold milk is still marketed by informal traders, often perceived as unreliable, which discourages the investment into more productive animals and better inputs. What should India be doing to reach those farmers still living on the margins and who have yet to reap the benefits of India’s milk boom?

Livestock ‘goods’ and ‘bads’: The roles of livestock globally–both positive and the negative—must be better understood, particularly why researchers and policymakers must draw a distinction between the developed and developing world when it comes to the future of livestock. The current public debate on livestock is dominated by concerns of the developed world on the negative environmental and health impacts of livestock. Experts at ILRI argue that this one-sided focus can leave the poor as victims of generalizations and justify the neglect of research needed to improve the sector’s environmental performance and management of disease risks, especially in parts of the world where the benefits of livestock, which provide most poor household’s with livelihoods, regular incomes and good nutrition, outweigh its problems.

The ILRI-ICAR Partnership Dialogue

Among those who led the Partnership Dialogue from ILRI are Jimmy Smith, a global expert on livestock production for developing countries who heads up ILRI in Nairobi, Kenya, and Purvi Mehta-Bhatt, who is head of ILRI’s Asia program and based in New Delhi. All of ILRI’s international board of trustees and senior management participated in the Dialogue, as well as the director general of ICAR, the directors of ICAR’s animal science institutes and several vice chancellors and deans, with a total of 12 countries represented. The high-level meeting was inaugurated by MS Swaminathan, India’s foremost geneticist renowned for his role in India’s ‘Green Revolution’, member of India’s parliament and chairman the MS Swaminathan Research Foundation. The Dialogue was ably facilitated by S Ayyappan, director general of ICAR and secretary of the Department of Agricultural Research and Education, and KML Pathak, deputy director general of animal sciences at ICAR.

Leaders in government, non-governmental, research and private-sector organizations made presentations and three thematic sessions generated discussions on smallholder dairy and small ruminant value chains, animal health and animal feed and nutrition. A high-profile white paper will be produced from the proceedings of this dialogue to distill the major recommendations made and serve as a basis for pro-poor and sustainable livestock policy interventions in the country.

Notes

Jimmy Smith, director general of the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI)

Jimmy Smith, a Canadian citizen, was born in Guyana, in the Caribbean, where he was raised on a small mixed crop-and-livestock farm. He was appointed director general of ILRI in April 2011. Before joining ILRI, Smith served for five years at the World Bank, leading the its Global Livestock Portfolio. Before that, Smith held senior positions at the Canadian International Development Agency (2001–2006). Earlier in his career, Smith had worked at ILRI and its predecessor, the International Livestock Centre for Africa (1991–2001). At ILCA and then ILRI, Smith was the institute’s regional representative for West Africa, where he led development of integrated research promoting smallholder livelihoods through animal agriculture and built effective partnerships among stakeholders in the region. At ILRI, Smith spent three years leading the CGIAR Systemwide Livestock Programme, an association of 10 CGIAR centres working on issues at the crop-livestock interface. Before his decade of work at ILCA/ILRI, Smith held senior positions in the Caribbean Agricultural Research and Development Institute (1986–1991), where he embarked on his career supporting international livestock for development. Smith holds a PhD in animal sciences from the University of Illinois, at Urban-Champaign, USA.

Purvi Mehta-Bhatt, head of ILRI Asia

Purvi Mehta-Bhatt is the head of ILRI’s work in Asia and is based in New Delhi, India. Mehta-Bhatt has been involved in many capacity development, outreach and technology transfer initiatives in India and around the world and brings over 16 years of experience in designing and implementing capacity development and stakeholder networking interventions. As director of Science Ashram in India from 1997 to 2005, she worked with more than 60,000 farmers and as country coordinator for the South Asia Biosafety Program. She serves on the board of several organizations, including the International Centre for development-oriented Research in Agriculture, the International Association of Ecology and Health and the Roadmap to Combat Zoonosis in India.

Read more about the ILRI-ICAR Partnership Dialogue on ILRI’s Clippings Blog: Lessons from India’s smallholder dairy successes can help developing world–ILRI’s Jimmy Smith, 8 Nov 2012.